Party congresses do not just decide the fates of China’s politicians; they also determine the reputations of observers who try to predict the outcomes. But even experienced analysts were humbled by the results of the 20th Party Congress, where institutional regressions allowed General Secretary Xi Jinping to achieve a remarkable consolidation of power.

While I previously explored the possibility of this scenario, I doubted its likelihood due to the serious downside risks that it poses. But now that Xi’s clean sweep is complete, I am left wondering why I and many others underestimated his resolve to scrap norms and strengthen his grip on the Chinese Communist Party (CCP).

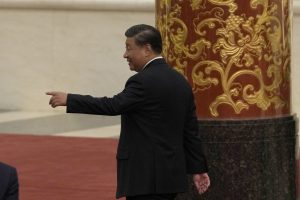

To recap, Xi filled the CCP’s Politburo Standing Committee (PSC) with allies, showing that informal rules around age and experience may now be applied selectively. He also crushed any semblance of factional balance, a conquest that was dramatically symbolized by Hu Jintao’s contentious exit. To celebrate his victory, Xi’s new team visited the site of the CCP’s 7th National Congress in Yan’an, invoking the supremacy achieved by Mao Zedong in 1945.

These events have made the 20th Party Congress a sort of requiem for China’s post-Mao “collective leadership” structure. In place of turnover norms and power sharing, Xi has resurrected a system of unified, strongman rule. To understand how Xi pulled this off, it is worth examining the latest amendments to party liturgy.

Enshrining the “Two Upholds”

Apart from personnel moves, a major outcome of this congress was to enshrine the “Two Upholds” (also translated as the “Two Safeguards”) in the CCP constitution. On the surface, it seems like yet another piece of numerical CCP jargon, used to signal loyalty to the top leader. The phrase was indeed mentioned by many officials at the congress.

But the Two Upholds also carries theoretical significance as a framework for reinstating strongman leadership. By adding it to the CCP constitution, party members are now duty bound to (1) uphold Xi’s “core” status in the party, and (2) uphold the party’s centralized authority.

Though not explained in the constitutional amendment, the meaning of the Two Upholds is extrapolated elsewhere. According to a leading party theorist, having “centralized and unified leadership” is necessary to achieve national rejuvenation and face “changes unseen in a century.” In this way, the Two Upholds effectively binds Xi’s power to the party’s leadership and the fate of the nation.

Enshrining this doctrine is the culmination of a multi-year effort to legitimize strongman rule in China. After acquiring “core” status in 2016, Xi went on to introduce his “New Era” philosophy at the 19th Party Congress in 2017. The Two Upholds first appeared in the CCP’s disciplinary regulations in 2018 and was further documented in the “historical resolution” announced in 2021.

Implications for CCP Turnover

Now that the Two Upholds doctrine has been constitutionalized, Xi’s domination of the reshuffle seems less surprising. Loyalists like Wang Huning and Zhao Leji have shown their ability to strengthen Xi’s core role and were therefore eligible for promotion. By contrast, the likes of Li Keqiang and Wang Yang have factional loyalties that make them inherently incompatible with the party’s new unified direction.

While these PSC moves have received much attention, Xi’s dominance of the wider Politburo and party-state apparatus is also remarkable. With the expected appointments of Li Qiang as premier and Ding Xuexiang and He Lifeng as vice premiers, Xi is bringing his inner circle into the heart of the national bureaucracy. This will serve to further obscure the already weakened lines of separation between party and state.

Similarly, the internal security apparatus (the “knife”) is now dominated by officials close to the top leader. These include Li Xi (anti-corruption tsar), Chen Yixin (minister of state security) and Ying Yong (likely supreme prosecutor), as well as the earlier appointments of Wang Xiaohong (minister of public security) and Tang Yijun (minister of justice). The military top brass also remain dominated by Xi allies, with the retention of 72-year-old general Zhang Youxia a strong indication of Xi’s firm hold over the “gun.”

Risks and Rewards

This centralization of power brings great risks and also potential rewards for the CCP. On the one hand, the party may be able to act with more unity and decisiveness on key policy issues. As SOAS researchers Steve Tsang and Olivia Cheung have found, Xi’s strongman approach has “unquestionably enhanced the capacity of the consultative Leninist state.”

On the other hand, Xi’s autocratic revival “has also inadvertently undermined the resilience of the system over the longer term,” state Tsang and Cheung. With no strong checks or balances and increasingly poor information flows, policy miscalculations seem more likely. Xi’s clean sweep also leaves little room to deflect responsibility and raises the prospect of a nasty power struggle when he eventually retires or dies.

But the CCP is all too aware of these dangers. Interestingly, the 20th Party Congress did not enshrine another formulation, the “Two Establishes,” which would have raised the status of “Xi Jinping Thought on Socialism with Chinese Characteristics for a New Era.” Contrary to initial reports, the Two Establishes was not ultimately added to the CCP’s revised constitution. It is also notable that Xi’s clunky “banner phrase” was not shortened to emulate Mao Zedong Thought, nor did Xi restore Mao’s party chairmanship or gain any new lofty titles.

From Institutionalism to Ideology?

While the 20th Party Congress was norm-breaking, it did perpetuate some long-standing conventions. For example, Li Qiang’s promotion to the PSC means that every Shanghai party secretary since Xi himself in 2007 (and all but one since 1987) has gone on to join China’s top governing body. (That makes the city’s new leader, Chen Jining, a name to watch for 2027.)

Before the congress, some observers questioned whether these other personnel moves matter anymore, given Xi’s political dominance. But by packing the top bodies with allies, Xi Jinping has shown that personnel and party institutions are still important as both a source and expression of power. Though immensely powerful, Xi remains a “captive of the party,” as Kerry Brown recently put it.

In this regard, the CCP has not entirely abandoned existing norms. But all told, the recent congress has marked a shift away from institutionalism and toward a strongman ideology as the party’s framework for apportioning power.

For analysts of Chinese politics, this means that institutionalist models are no longer as reliable as they once were. Instead, we might spent more time understanding Xi’s “New Era” worldview. In a system of strongman rule, the strongman’s thoughts are what matters most.