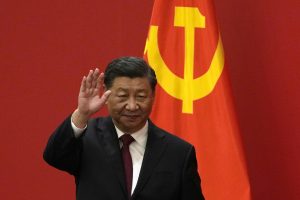

Xi Jinping’s third term as general secretary of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has begun. Xi’s own speech and the personnel announcements made to date have exhibited a strong emphasis on national security to further strengthen control over Chinese society, while persuading CCP members and the Chinese people, including minority groups and the Taiwanese, to share the same “dream.” Moreover, although the unity required for this has also been a point that Xi has emphasized, personnel announcements have made it evident that this “unity” is not defined by diversity, but rather by everyone facing the same direction and supporting Xi Jinping.

Here are some takeaways from Xi’s speech and the personnel announcements.

First, the general secretary system has been favored over the party chairmanship system, meaning a collective leadership system was maintained. Almost all members of the CCP Central Committee are now people believed to belong to Xi’s faction, and none of the Central Politburo members are women. This is perhaps to show that unity means belonging to the Xi faction. However, although the decision-making process of CCP personnel affairs has always been opaque, it is even more so this time. One example: The number of Central Politburo members is now 24, one less than the usual 25.

Second, unity has been emphasized in both speeches and personnel announcements. This is probably because the CCP now thinks it is uncertain if China can achieve its goals of becoming a modern socialist country by 2035 and a great modern socialist country by 2049 amid the economic slowdown, including COVID-19, and pressure from the United States and other advanced countries. This is why it is trying to strengthen its pro-Xi definition of unity of the party and Chinese people. This is a manifestation of a sense of crisis.

Third, no successor has been appointed. If there had been two new Politburo Standing Committee members, they would have been considered de facto successors, but there were in fact four. The Central Military Commission also has no “civilians” other than Xi himself. (Xi is on the military register.) This has made it likelier that Xi Jinping will continue as general secretary for the next 10 years.

Fourth, a number of conventions were broken, among them apparently the conventions of retirement at the age of 68 and of a former vice premier becoming the premier. Of course, it is possible that Li Qiang will be vice premier for the next few months and then become the premier in March 2023. In any case, the institutionalization within the party that had been ongoing since the eras of Jiang Zemin and Hu Jintao has collapsed, at least in terms of personnel matters. As a result, generational change has been delayed, and China’s “seventh generation” of 50-year-olds, mainly born in the 1970s, have missed out on becoming Central Politburo members. It may be that the Xi Jinping is distrustful of the younger generations who did not experience the Cultural Revolution.

Fifth, there are issues with responsibility for economic and fiscal affairs. Li Keqiang, Wang Yang, Hu Chunhua, and other reformists have been purged, and although He Lifeng is there, there has been a weakening of the officials in charge of the economy, which is a concern. Fewer Central Politburo members are in charge of monetary and fiscal matters. The more emphasis there is on the “common” in “common prosperity for all” (and in this context, “common” means distribution), the more the line of “reform and opening up” will be suppressed. Given that reform and opening up is what drives cooperation with the West, this will also affect foreign policy implications.

Sixth, although some words about Taiwan have been included in the Party Constitution, there has been no significant change in expression. The basic stance is to “win without fighting” by 2049. China regards the Taiwanese as a part of the Chinese nation and assumes that they will share the same “dream,” which is why the official goal is to incorporate Taiwanese society. In other words, they will push Taiwanese society toward unification by continuing to increase military pressure, to penetrate society with cyberattacks and disinformation, and to apply economic sanctions and similar measures. The problem is what will happen when Xi Jinping comes to regard this policy as being ineffective, because that is when he will likely increase the level of military pressure.

Seventh, the question is how to deal with dissatisfaction within the party over these personnel affairs, an unemployment rate of nearly 20 percent, the economic slowdown, and social dissatisfaction with the COVID-19 countermeasures. The Xi administration will likely act preemptively against social dissatisfaction by commanding big data and whole-process democracy, while at the same time using “national security” as a shield to eliminate troublemakers through digital surveillance and control networks at the basic social level. Yet the “happy surveillance society” can only exist as long as the CCP continues to deliver on its promises of affluence and convenience. Will this continue under the new system? Is it ultimately possible for Xi Jinping’s dream to coincide with the dreams of the CCP members and the Chinese people, encompassing all ethnic groups? That will be the critical question as he begins his third term.