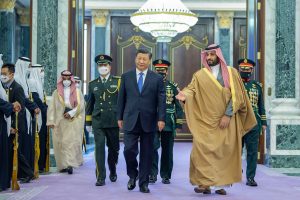

Last week, China’s President Xi Jinping visited Saudi Arabia for a historic multi-day visit to attend three major regional events: the Saudi-China summit, the China-Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) summit, and the China-Arab Summit. During the visit, Xi and Saudi King Salman hailed a new era in Sino-Saudi bilateral relations.

The grandeur of Xi’s visit sent powerful signals that Sino-Saudi ties are entering a new period of rapid development. For China’s other Gulf partner, Iran, the strengthening of ties could mean a distinct disadvantage for Tehran in its protracted rivalry with Saudi Arabia.

China’s relationships with Saudi Arabia and Iran are complicated. China’s leadership has to carefully manage its relations with both to maintain its neutrality and protect its own economic, political, and security interests. Every few years, Beijing goes on a diplomatic offensive in the Gulf, sparking speculation from observers that China is favoring one side over the other in the Saudi-Iran dispute.

Although China maintains close relations with both countries, Saudi Arabia has emerged as one of Beijing’s leading strategic partners in the region in recent years. Xi’s December visit to Riyadh is again generating speculation that Beijing’s actions could offset a careful diplomatic balancing act Chinese officials have maintained with both sides.

Beijing has worked tirelessly to stay out of the fray of the Gulf rivalry. The challenge, however, is that any advantage provided to one side – for instance, rumors of a $4 billion Saudi purchase of Chinese defense equipment – could be perceived by the other as a disadvantage. To avoid the perception of privileging Tehran or Riyadh, China has actively pursued a policy of equivalency in its diplomatic engagements and military cooperation.

For instance, in 2016, Xi signed comprehensive strategic partnership agreements with both Saudi Arabia and Iran, within weeks of each other. In both 2017 and 2019, Beijing held separate military drills with Iran and Saudi Arabia, spaced only a few weeks apart, to avoid conveying the wrong message. And, as Xi concluded his Saudi Arabia trip on December 10, China’s ambassador to Tehran announced Chinese Vice Premier Hu Chunhua would visit Tehran the week of December 12.

Despite Beijing’s level of care and a tacit tolerance for its relations with the other side, both Iran and Saudi Arabia have expressed frustration with China over its dealings with the other. Following Xi’s trip to Saudi Arabia, Iran’s deputy foreign minister for the Asia-Pacific summoned China’s ambassador to Iran in a rare show of protest on December 12. Tehran wanted to express dissatisfaction over Beijing’s joint statement with GCC nations, highlighting statements of support to the GCC regarding disputed islands in the Straits of Hormuz that Iran found concerning. The China-GCC joint statement also stressed the importance of the Iran nuclear issue, as well as linking Iran to “destabilizing regional activities,” “support for terrorist organizations,” as well as the “proliferation of… drones.”

Meanwhile, in 2021, Saudi officials expressed similar concern over China’s 25-year agreement with Tehran. The ambitious partnership set off red flags in Saudi Arabia, prompting Saudi officials to attempt to discourage Beijing from stronger ties with Iran.

Beijing’s balancing act, while not perfect, is reinforced by strong economic ties with both countries and bilateral trust, which has been cultivated between China and both countries over the past decade. This trust has been key in allowing Beijing to weather the occasional diplomatic foible and course correct when Tehran or Riyadh raise a complaint.

The question remains whether China’s more aggressive GCC outreach this month is a temporary swing of the pendulum from Iran toward Saudi Arabia or a new pro-Saudi status quo. The former is more likely than the latter.

Saudi Arabia and the broader GCC may be a near-term geopolitical priority for Chinese officials due to the immediate benefits of deepened ties with Saudi Arabia and Iran’s present domestic challenges. China increasingly prefers predictable, stable, and high-return investments. Beijing’s economic ties, investment, and energy ties with Riyadh have produced significant gains with limited risks in the past two years.

Iran, meanwhile, has not yielded such gains for Chinese investors in the short term. Chinese businesses in Iran remain bogged down with concerns over the risk of triggering U.S. sanctions. Meanwhile, a lack of progress in negotiations over a new nuclear deal with Iran has delayed any benefits of Beijing’s $400 billion agreement with Tehran. This is to be expected, given Beijing and Tehran’s strategic cooperation roadmap has a timeline of 25 years, compared to just five years with Saudi Arabia. For China, its Iran partnership is a strategic waiting game, one which requires extensive diplomatic attention over the long term.

Beijing’s next steps following Xi’s visit will likely aim to reassure Iran of China’s neutrality and signal equivalency in the relationship. This strategy will follow a familiar pattern. First, China will deploy a senior-level official to Tehran to re-enforce its neutrality in the Iran-Saudi Arabia rivalry and emphasize China’s longstanding policy of non-interference. Then, Beijing will engage in careful diplomacy to communicate with both countries to prevent further escalation with Iran while avoiding the impression of backstepping with the GCC. While a vice premier is on the docket for an in-person Iran visit, the recent Iranian opposition to China’s joint statement with the GCC may likely require higher-level Chinese engagement, maybe even a head of state call.

China will continue to deepen relations with both Tehran and Riyadh while remaining above the fray in the protracted Iran-Saudi Arabia rivalry. However, its increasing economic engagements with Saudi Arabia, the GCC, and the broader Arab world are putting pressure on Iran. From Tehran’s point of view, the strengthening of Sino-Saudi ties provides Saudi Arabia a net advantage, while disadvantaging Iran’s pursuit of international legitimacy. This has the potential to affect China’s own interests in the Gulf if it does not restore its diplomatic balance.