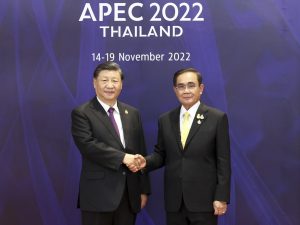

Addressing APEC business leaders in Bangkok, Thailand last month, China’s President Xi Jinping commented on the East Asia miracle – the export-oriented growth model centered on Japan 40 years ago, and proposed building an “Asia-Pacific Community with a shared future.”

The conception of an East Asian Community is hardly new. It was first raised by Prime Minister Koizumi Junichiro in the early 2000s, and became the guiding ideology of Japan’s Asian diplomatic and economic policy during Hatoyama Yukio’s administration, at a time when Japan was the largest economy in Asia.

In a speech delivered to the Shangri-la Dialogue in May 2009, Australia’s Prime Minister Kevin Rudd, too, advanced a proposal for an Asia Pacific Community aimed at building integrated regional institutions to counter China’s rise; it did not significantly affect Asia-Pacific regionalism.

Most discourse about China’s regional influence – and thus Xi’s concept of an Asia-Pacific Community – is preoccupied with the hard question of how to tame China’s rise, as the question itself offers an academically puzzling and politically intriguing case. This essay aims to decode Xi’s concept, explain how it is different from those proposed before, and draw implications for the Asian community.

A Power Balance Shift in Asia

As Henry Kissinger has noted, great power competition is full of uncertainty and unpredictability and subject to potentially significant shifts in the balance of power.

Since the end of the Cold War, the United States has been the only superpower in the world, and the U.S.-led world order has been grounded in core U.S. values of liberty and democracy, which are shared by many Asian countries.

The U.S.-led world order has been possible because of its economic and military power, and because of its role as a provider of global public goods, including defending its allies in war.

With China’s rise as the world’s second-largest economy, what Xi wants is to promote an alternative order in which sovereign nations’ unique values should be respected. Xi has emphasized the importance of all humankind’s equal rights to develop and grow in prosperity, whatever their ideology or political values.

China has been actively increasing its contribution to global public goods by, for example, providing free COVID-19 vaccines to poor countries, and by investing in infrastructure along the Digital Silk Road.

In the dynamic power balance between the United States and China, competition between the two manifests at three layers: on the surface, it is a trade war; in the middle, it is a competition for technological leadership; and at its core, it is the competition for a world order. Unlike other great powers in history that challenged incumbents, China’s rapid rise, both economically and technologically, has benefited greatly from the economic interdependence of the two countries.

While a new world order is not on the horizon, the U.S.-led attempt at decoupling China from the global supply chains, especially the supply chains of critical technologies and strategic minerals, is significantly influencing the geopolitical landscape, especially in Asia, including Australia.

In Asia, the shift of power balance has particularly significant geopolitical consequences. Japan’s GDP was nine times China’s in 1991 but had declined to about one-fifth of China’s by 2021. China today accounts for more than half of Asia’s economy and is the largest trading partner for most countries in Asia. With such a shift of economic power, the U.S.-supported Asian model centered around Japan is broken, and a new order of governance in trade, finance, and digital sphere that matches the rebalancing of power in Asia is urgently needed.

The great power competition has caused many Asian countries to feel they have been caught in the middle. Lee Hsien Loong, the prime minister of Singapore, summed up this conundrum, saying, “It will not be possible for Singapore to choose between the United States and China, given the extensive ties the Republic has with both superpowers.” That sentiment is shared by countries such as South Korea and Japan, the leaders of which both met with Xi during the recent summits.

In Xi’s vision of an Asia-Pacific Community with a shared future, China is the “hub,” connecting with each individual nation in a hub-and-spokes model of a distributed supply chain network.

To a large extent, this is already happening. Amid the trade tensions between the United States and China, some of China’s manufacturing facilities were relocated to its Asian neighbors, especially ASEAN countries. Contrary to a commonly-held view that these relocations have “hollowed out” China’s manufacturing power, rather, assembly and final production in those countries have become an extension of China’s mega supply chain, relying on the supply of intermediate goods from China and the export of the final goods from those countries, to avoid increased tariffs on goods exported directly from China.

The fact that China and ASEAN are now each other’s largest trading partner is a manifestation of this change. According to China’s customs data, in the first 10 months of 2022, the volume of trade between China and ASEAN increased 13.8 percent, reaching $798.4 billion. Intermediate goods account for over 60 percent of this trade, suggesting the two parties are highly interdependent and embedded in each other’s production networks. China’s mega supply chain is built upon its industrialization in many backbone heavy industries, such as machine tool building, steel and chemical production, which will take its Asian neighbors a long time to catch up with.

If Xi’s vision can be realized, even if the United States were able to pursue a de-Sinicized strategy in supply chains, an interdependent Asia-Pacific Community with China as a “hub” might help Xi secure China’s position in the world or, at least, deter the U.S.-led effort to decouple.

Implications for the Asian Community

There are several reasons that, for the foreseeable future, it will not be feasible for Xi to realize his vision of building an Asia-Pacific Community, at least at the governance level.

First, most of China’s Asian neighbors have accepted the U.S.-led world order of freedom and democracy. A rising China with an authoritarian regime is perceived as a security challenge to those countries.

Second, for a country to take a global/regional leadership role, it needs to have four dimensions in its structural power: (1) the capacity for the provision of security for itself and for other countries; (2) dominance in the production of goods and services; (3) being a key part of the finance and payment system in global trade; (4) significant contributions to global knowledge. While China is a dominant power in the production of goods, it misses all the other elements.

Third, despite technological advancement over the past three decades, China still faces some critical technology bottlenecks, and it needs collaboration in science and technology with the West.

Can Xi achieve his goal? Besides being a pragmatist, he is also a realist. According to Sun Tzu’s “Art of War,” when you can’t beat an army of allied adversaries, you conquer them one by one. This is perhaps precisely what Xi was busy doing at one-on-one meetings with his Asian counterparts during last month’s summits.

As a first step, Xi needs to make sure that China’s market will be open to its Asian partners, and every nation will benefit from this intra-Asia production network.

Implications for Australia

Australia, as a resource provider in the China-centered production network, has benefited greatly in the past 20 years.

Fifty years ago, the then-opposition leader Gough Whitlam led a delegation to China, which, subsequent to his party’s election to government, secured Australia’s diplomatic relationship with the PRC, even before the United States did. Whitlam managed to not just show Australia’s loyalty to its strategic ally – the U.S. – but achieve Australia’s own goal as a middle-power nation in the South Pacific. Thus, Whitlam has been remembered not just for his courageous action of reaching out to break the power balance during the Cold War, but also his move to reposition the country in alignment with Asia by leading to the ending of the country’s “White Australia” policy.

The geopolitical landscape Australia is facing today is vastly different from Whitlam’s time. Fifty years ago, China was a political lever on a grand chessboard between the United States and the Soviet Union, and, for Australia, siding with China was risky but not damaging to its alliance with Washington. Today, China’s rise is challenging the dominance of the U.S. in trade, technology, and world order, and siding with China carries serious risks and possibly heavy consequences for Australia.

However, the reality that Australia needs to face is, in the case of bifurcation in supply chains, Australia’s endowment will make it less attractive if it is part of the “friend-shoring” solution that the U.S. is aiming to build to exclude China. Australia will find it hard to replace China as a downstream partner and will face more competition in resources and agricultural products in the new supply chain. One might wonder what Whitlam’s decision would be were he alive today.