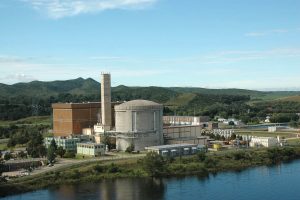

This February, China’s state-owned nuclear company, the China National Nuclear Corporation, committed itself to building an Argentine nuclear plant, Atucha III. Atucha III had experienced prior starts and stops during the three Argentine presidencies since its founding agreement in 2015. China’s commitment to the plant dovetailed with Argentine President Alberto Fernández’s February 2022 trip to China and Argentina’s subsequent insertion into China’s Belt and Road network. Taken together, this fast-paced cluster of China-Argentina collaboration appeared to suggest that Atucha III’s construction was suddenly likely, perhaps imminent.

Yet in April, amidst domestic economic pressures, Argentina asked China to fully finance Atucha III’s construction, versus China’s commitment to fund 85 percent of the project, which has an estimated overall cost of $8 billion. In September, reports suggested that Argentina wanted to domestically produce the plant’s fuel assemblies, which would further slow the timeline. As of this writing, the project remains under planning with ambiguous next steps.

Argentina’s stalled nuclear collaboration with China underscores that for viable new energy sources to be fully functional, they will require long-term stewardship that includes diversified inputs and nonpartisan, consistent government funding. Thus far, Atucha III appears to lack these two crucial ingredients for success, which allowed Argentina’s preceding nuclear plants to begin operations.

First and foremost, Atucha III does not have the diversified material and human capital inputs that two other recent Argentina plants, Atucha II and Embalse, enjoyed. When Argentina constructed Atucha II, the country solicited German, Spanish, and Brazilian expertise before finalizing its strategic plan. Argentina also undertook a significant human capital investment while constructing Atucha II, boosting the plant’s dedicated personnel from 150 to nearly 7,500 at the project’s height and conducting intensive technical training for all.

Although Embalse has been active since 1984, it underwent a refurbishment between 2010 and 2019. In the process, Argentina collaborated with Canadian and Italian firms to obtain diversified material and human capital inputs, tasking Canada with technology transfer and Italy with construction.

By contrast, Atucha III appears largely dependent on Chinese technology with limited, if any, additional international input. Argentina may be rectifying that by seeking to domestically produce Atucha III’s fuel assemblies, as reported in September. However, whether this diversification occurs remains to be seen.

Second, in addition to diversified material and human capital inputs, Atucha III lacks the nonpartisan and consistent government funding that served Atucha II and Embalse well. Atucha II’s construction was a drawn-out process between 1981 and 2015, which nearly cratered during Argentina’s economic crises of the 1990s and early 2000s. However, the government reemphasized its financial commitment to the project repeatedly during the 34 years, and accelerated Atucha II’s funding from 2006 until its completion in 2015. Embalse’s refurbishment cost $2.15 billion, a hefty sum that governments on both the political left and right agreed to pay between 2010 and 2019.

In comparison, Atucha III’s project funding will likely come from Chinese, not Argentine, authorities, after Argentina requested that China fully finance construction in April. By placing Atucha III’s funding outside its control, Argentina may also cede control over the project’s pace and the operating performance of an important new energy source.

The input diversification and nonpartisan, consistent government funding that will likely unblock Atucha III’s stalled progress are relevant considerations beyond Argentina – especially with Europe struggling with a looming energy crisis. Any countries seeking to secure alternative fuel supplies through a collaborative process would benefit from undertaking these two steps.