Xi Jinping’s ascension, and his declaration of a “new era,” has sparked renewed interest in – and comparisons with – the preceding era of “reform and opening.” Begun under Deng Xiaoping in the late 1970s, reform and opening marked the beginning of what is often referred to as China’s “economic miracle” and its transformation into a modern economy. But the “miracle” was nowhere near as simple as is often assumed.

In his latest book, “China After Mao,” Frank Dikotter, author of “The People’s Trilogy” turns his attention to China’s post-Mao era, to the tumultuous years of economic reform starting in the late 1970s. As Dikotter emphasizes, however, political reform was never part of the agenda – despite the hopes of many Western analysts and politicians. The “economic miracle” was in fact a winding road, marked by unintended consequences, abrupt reversals, and internal arguments – all aimed clearly at the goal of maintaining Chinese Communist Party control over China’s economy, politics, and society.

The Diplomat’s Shannon Tiezzi interviewed Dikotter via email about “China After Mao” and the ways China’s economy and governance changed – and, equally importantly, how they didn’t – since 1976.

“‘Red China’ never went away,” Dikotter told The Diplomat. “It’s just that people [abroad] fell asleep.”

Your book repeatedly describes instances of Chinese officials reacting to events that were already happening in their policymaking. Time after time, economic reforms are made not because the government decided on them, but because they were already happening on the ground and could not be stopped (for example, the end of agricultural communes, price reform, and the rise of local markets). Should we mentally reframe China’s “economic miracle” as something that happened not because of, but in spite of the Chinese government?

I think that would be accurate for the countryside up to 1982, when the People’s Communes collapsed, hollowed out by the villagers. People in the countryside lifted themselves out of poverty, ignoring repeated campaigns forbidding families from cultivating the land on their own. But not so afterwards.

In fact the key word is “unintended consequences.” The leadership was taken aback by the economic growth coming from the countryside and decided, in 1984, to apply the same approach to the state enterprises in the cities: With the contract system these enterprises could retain any surplus produced over and above state quotas. But it caused a scramble for raw materials, which led local governments in turn to erect road blocks and checkpoints to prevent outsiders from poaching them (and villagers from selling their produce elsewhere at a better price). Instead of a unified national economy it resulted in a lose patchwork of independent fiefdoms. It also caused massive inflation, feeding right into the unrest in the spring of 1989.

The list goes on, without even mentioning the one-child policy. In 1992 Deng Xiaoping proposed to attract more foreign investment by allowing local governments to lease the land. The result was that land became a collateral, with the central government increasingly caught in a dilemma. If it allows the real estate sector to decline it will be saddled with the enormous debts accumulated by local governments, not to mention all the hidden debts carried by local government financing vehicles.

Another common thread through the book is the CCP’s paranoia about foreign infiltration. This was once framed as “bourgeoisie liberalization,” a term not much in vogue today. How has the CCP’s conception of what is “too foreign” – and the targets of its ideological “clean ups” – evolved since the 1970s?

Another common thread through the book is the CCP’s paranoia about foreign infiltration. This was once framed as “bourgeoisie liberalization,” a term not much in vogue today. How has the CCP’s conception of what is “too foreign” – and the targets of its ideological “clean ups” – evolved since the 1970s?

Very little of substance has changed. In 1957 the American Secretary of State John Foster Dulles came up with the notion of “peaceful evolution.” He suggested that the World Bank and other organizations should economically assist satellite states of the Soviet Union in the hope that, with economic progress, they would evolve peacefully towards a democratic system.

This is precisely what happened on June the Fourth, 1989, when the people in Poland voted the Communist Party out of power at the ballot box. Hungary and other East European countries followed. Beijing was taken aback, and in the summer of 1989 Jiang Zemin made “peaceful evolution” one of the key threats to the rule of theCommunist Party. It is still seen as a great peril today.

Every time a Bill Clinton, a George Bush, a Kevin Rudd, or a Tony Blair talked about how, in the wake of economic reform, political reform would inevitably come to the People’s Republic of China, they were offering all the evidence the leadership needed to confirm them in their view that foreign powers were trying to infiltrate and subvert power through “peaceful evolution,” their aim being the overthrow of the Communist Party. They may have smiled politely, but they became even more determined to contain the flow of “foreign things.” Everything, from Mickey Mouse to non-governmental organizations, is seen as part of a plot to force the country to “evolve peacefully.” You will have noticed the gradually increase in control over “things foreign” over the past couple of decades in general, since 2008 in particular.

Even while constantly fearing infiltration and ultimate defeat by Western forces, the CCP also has remained steadfast in its belief about the West and capitalism’s inevitable decline. How has this narrative changed, and how do party leaders continue to justify this belief despite 100 years of waiting in vain for capitalism to collapse in on itself?

An old communist joke has it that Marxists are good at foretelling the future but find predicting the past much more difficult. Marxism, of course, is a philosophy that has been foretelling the imminent collapse of capitalism for well over a century, as you point out. It is a vision the leadership in Beijing firmly embraces. The reason why Mao decided to have a rapprochement with the United States in 1972 is because he believed that the Soviet Union was a much greater threat.

When the United States withdrew from Vietnam, Deng Xiaoping interpreted it as proof that the imperialist camp was on the decline. He, too, tried to shore up support from the United States and Japan against their common enemy, the polar bear. We imagine that when fact-finding missions were sent to the United States in the late 1970s, they were taken aback by the sheer wealth they saw. Not quite: These missions reported back to Beijing that the Americans suffered from inflation, unemployment, debt and a looming economic crisis. “We must seize these extremely favorable conditions,” the Ministry for Foreign Trade concluded in 1979.

The implosion of the Soviet Union in 1991 took them completely by surprise. Overnight the slogan changed from “Only Socialism Can Save China” to “Only China Can Save Socialism.”

They have been expecting the downfall of capitalism since 1921, and they are still waiting. A key moment came in 2008: With the world crisis in the wake of the collapse of the Lehmann Brothers, the leadership became convinced that they were witnessing the beginning of the end. Their faith in the superiority of socialism seemed to finally pay off. One result was that hubris set in, with a more strident tone in foreign affairs, including the so-called wolf-warrior diplomacy. Another was endless lectures on how democracies should run their affairs. Wen Jiabao personally took to task his interlocutors at Davos in January 2009 for believing in capitalism, upholding socialism instead as the model to be followed.

But the most fervent believer in the ultimate demise of capitalism must be Xi Jinping, next to Wang Huning.

At one point you write of China’s banking woes: “A strongman willing to purge, slash, burn and punish on a scale vast enough to bring every local leader to heel was required” to push through the necessary reforms. Do you think Xi Jinping is such a strongman – and if so, is he actually willing to use his power to do the hard work of restructuring China’s economy?

In a one-party state, politics is always in command. The hard work is not in the economy, which is secondary, but in politics, or in other words power. You must remember that the organization of the party was left severely damaged by the Cultural Revolution, when Chairman Mao allowed ordinary people, briefly, to take to task any party member, whether a local cadre or a powerful minister in the capital. He called it “Bombard the Headquarters,” hoping that “the masses” would ferret out all real or imagined enemies of the revolution, including those who might oppose him. It left the party in tatters, not least in the countryside where many local cadres allowed the villagers to undermine the collectives, provided they could get the economy to grow.

Then Zhao Ziyang allowed local governments in 1984 to benefit from surpluses produced by local state enterprises. Most of all, in 1984 he gave the local branches of state banks more leeway in making decisions about local lending. In other words he allowed a great deal of power to shift from the center toward local governments. That is what the quotation you invoke refers to. Jiang had neither the will nor the power to rein in local fiefdoms; he was forced to compromise. But over the years a measure of clout has been restored to the center, and since 2012 Xi Jinping has become determined “to bring every local leader to heel.” That this should come at the expense of the economy, with endless campaigns against corruption and lockdowns against a virus, should not come as a surprise.

Some Chinese leaders (often premiers, like Zhao Ziyang, Wen Jiabao, most recently Li Keqiang) have been labelled “reformers” and there is at times a wistful sense that China today would be more open politically and economically had they had more influence. But as your book repeatedly shows, none of these leaders ultimately questioned the CCP’s right to rule, nor did they embrace democracy or a separation of powers. Do you think the “reformer” label is useful in describing Chinese politicians?

We tend to forget that the economies of communist countries have changed a great deal over time. Even under Stalin, in the 1930s, foreign businessmen cutting deals in Moscow were impressed by the luxury hotels, the world-class restaurants, the skyscrapers, not to mention the regime’s showpiece, an ornate, beautifully designed subway system. In Poland, even at the height of communism, the majority of all shops, including restaurants, were private. Two-thirds of arable land was cultivated by private farmers in the 1980s, a fact that would be considered intolerable to Beijing today.

After 1949, the Communist Party took several years to confiscate all the means of production, meaning that by 1956 commerce and trade were functions of the state while in the countryside the villagers had lost the land and control over their harvest. None of the reformers has seriously envisaged letting go of what was acquired through so much violence in the 1950s, quite the opposite.

When Deng Xiaoping suggested in 1992 that land should be leased to attract foreign capital, he put it very succinctly: Foreign Tools in Socialist Hands. As he pointed out, the land belongs to the state, the banks belong to the state, so there is nothing to fear from more foreign investment. It is precisely the ownership of the means of production that has given the party the confidence to attract foreign capital, not to mention join the World Trade Organization and outcompete every member state, even Bangladesh in the production of garments.

The point is that since 1976, changes have been introduced to a rigidly collectivized economy in order to build up socialism, not to abandon it. And also, of course, to create the greater wealth required to resist the imperialist camp, not least the plot of peaceful evolution.

Several analysts have argued that China has entered a new period under Xi Jinping, one that is qualitatively different from the rest of the post-Mao era. Based on your analysis of “China after Mao,” would you agree that China is really in a “new era”?

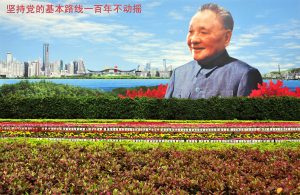

Not at all. Kevin Rudd, having failed to understand very much about China when he was prime minister of Australia, now wants to tell us that “Red China is Back.” But “Red China” never went away. It’s just that people like Kevin Rudd fell asleep. Or, alternatively, it is that they were too busy making money in China to pay attention when the leadership in Beijing, year in, year out, pointed at the importance of the Four Cardinal Principles enshrined in the constitution in 1982: uphold the leadership of the party, uphold the socialist way, uphold Marxism-Leninism and Mao Zedong Thought, and uphold the dictatorship of the proletariat.

The last time this was emphasized was at the 20th Party Congress in October 2022 by Xi Jinping. In this he follows his predecessors and, like them, he closely adheres to the constitution. I suggest we all read it, much like we should read the constitution of the United States when dealing with or living in the United States.