Japanese Prime Minister Kishida Fumio had a busy week: From January 9 to 13, he visited five of the six other G-7 nations. The tour was meant to confirm fellow G-7 members’ positions on the issues that will be raised at the G-7 summit to be held this May in Hiroshima. Overall, Kishida deemed his visits to France, Italy, the United Kingdom, Canada, and the United States a success. He also intends to meet with German Chancellor Olaf Scholz at some point before the summit.

Kishida’s visit to the United States was significant for the broad range of issues that were brought up – from Japan’s overture to the United States to return to the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) to an agreement on space cooperation – and the historic nature of changes in Japan’s defense posture preceding Kishida’s visit.

Last December, Kishida’s government released three key security documents: the National Security Strategy, the National Defense Strategy, and the Defense Buildup Program. One of the major changes in the new documents is Japan’s decision to acquire counterstrike capabilities. Related to the adoption of the new strategies, the government has also committed to a massive increase in defense spending, from 1 percent of GDP in 2022 to 2 percent of GDP in 2027.

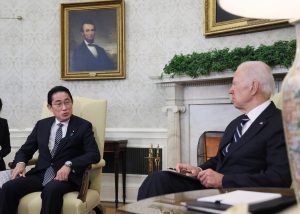

During Kishida’s summit meeting with U.S. President Joe Biden, Biden praised Kishida’s efforts to increase Japan’s defense capability. Biden and Kishida affirmed their shared criticisms of Russia, China, and North Korea, as well as their shared commitments to the free and open Indo-Pacific and to “modernizing” the military alliance and increasing the alliance’s deterrence and response capability. For example, Kishida and Biden are both in favor of Japan’s plans to procure U.S. Tomahawk cruise missiles.

Biden also reassured Kishida of full U.S. support for the defense of Japan, “using its full range of capabilities, including nuclear.” One can only wonder what Kishida’s inner reception to this reassurance was, as he is personally committed to abolishing nuclear weapons from the world. Biden also reiterated that Article 5 of the Japan-U.S. Security Treaty covered the disputed Senkaku Islands, which are administered by Japan but claimed by China as the Diaoyu Islands. In a separate conversation, U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken also confirmed that an attack in space would trigger the mutual defense provision in the Security Treaty.

While the two sides also discussed shared concerns over Russia’s ongoing war in Ukraine and North Korea’s weapons development, concerns about a possible conflict with China over Taiwan or the disputed Senkaku/Diaoyu islands in the East China Sea were front and center.

During the 2+2 talks between Blinken, U.S. Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin, Japanese Foreign Minister Hayashi Yoshimasa, and Japanese Defense Minister Hamada Yasukazu, the United States announced the establishment of a U.S. marine littoral regiment (MLR) in Okinawa. The purpose of the MLR, which emphasizes mobility, is to respond promptly to an emergency on Japan’s remote islands and enhance deterrence against China. Increased mobility – including the possibility of deployment on the Nansei Islands – is also emphasized in Japan’s planned changes for the Ground Self Defense Forces (GSDF) personnel in Naha, Okinawa.

It may be easy to get caught up in how much is changing in the Japan-U.S. security relationship, and a lot of these changes are momentous. However, as Craig Kafura argued, “While Japan’s recent moves to strengthen its defense posture have been met with strong support among both the American and Japanese publics” – and American and Japanese officials, as demonstrated by the recent meetings in Washington – “that doesn’t mean the work is done. Instead, it’s just begun.” U.S. and Japanese officials still face the challenges of convincing their respective publics.

American officials need to convince the American public that U.S. security is tied to Asia, not Europe, and Japanese officials need to convince the Japanese public to bear the burden of increased taxes and new military bases, storage units, etc. in their neighborhoods.

High-level international agreements still need to be implemented at the local level, and Tokyo does not have a strong track record of understanding or managing local opposition well. Will Tokyo defuse local opposition better this time? And if so, will it be because politicians in Tokyo have gotten better at heading off local opposition or because local populations are more willing to cooperate with Tokyo due to a greater awareness of the dangers that China poses? Alternatively, Tokyo might get its way without properly addressing local concerns because the Japanese government is more willing to use strong-arm tactics amid a rising threat perception vis-a-vis China.

Though Kishida deserves much credit for his numerous defense-related accomplishments thus far, the U.S. side should keep its expectations in check to avoid disappointment later.