In 2004, I traveled a thousand miles in the eastern Tibetan plateau by local bus, hitchhiking, and finally on a second-hand motorcycle, which I rode over 17,000-foot passes so remote I felt like the last man on earth. I drove through villages with flowers blooming from earthen walls, where men walked up and down dirt streets in cowboy hats, with chunks of turquoise braided in their hair.

At this time, the Tibetan Autonomous Region (TAR) required special permits to enter, and Lhasa was being reconstructed as a Chinese city, but life was different in the traditionally Tibetan areas to the east of the TAR proper, in today’s Yunnan and Qinghai provinces. The communities I experienced seemed relatively untouched by industrial development or impositions of national authority, despite having survived gulag conditions in recent decades.

While Chinese “modernization” projects focused on the TAR, other ethnically Tibetan areas remained a raw, wild region of vast plains, golden barley fields beneath incomprehensibly blue skies, nomadic yak herders, and fortress-like Tibetan houses perched on mountain ridges. The earth unfurled in primordial colors and forms, and Tibetan culture appeared to be inextricably rooted to the land, as if the two were mutually sustaining and could not be separated.

But over the next 15 years, as I returned to to the eastern Tibetan plateau I saw destructive dam and mining projects multiply exponentially, displacing autonomous Tibetan communities into resettlement zones. Armored vehicles appeared in towns, and platoons of People’s Liberation Army soldiers patrolled Buddhist temples with assault rifles. Tibetans became a minority in their own territory due to the influx of ethnic Han Chinese migrating from lowland areas for work or business opportunities.

Pristine natural landscapes were transformed into construction zones crowded with lorries, backhoes, and gravel crushers, and the high thin air of the roof of the world became heavy with dust and diesel exhaust. Traditional villages were expanded into small cities as thousands of displaced Tibetans were relocated from their earthen homes and ancestral grazing lands to live in pre-fab concrete shells.

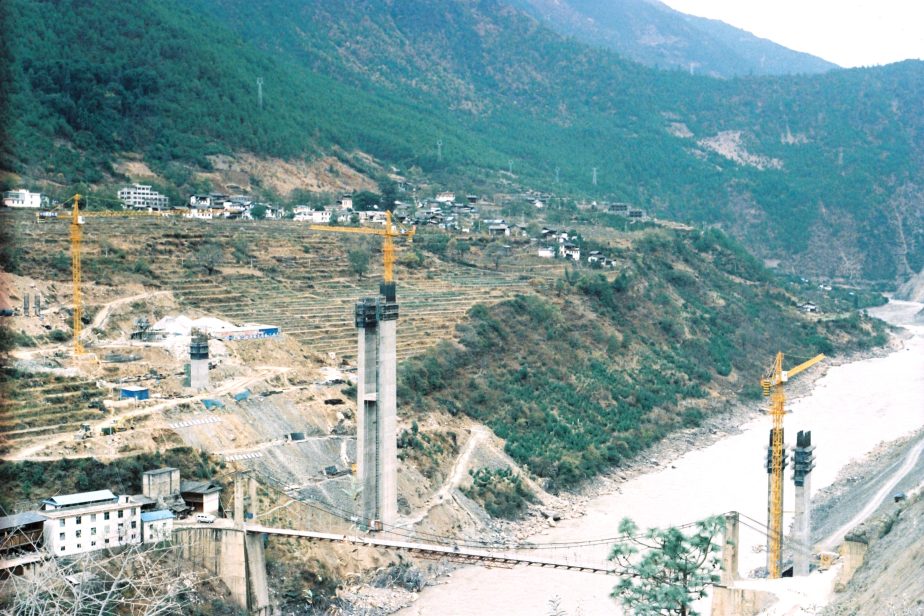

The Tibetan village of Cizong on the upper Mekong, with hundred year-old terraced vineyards, at the start of its transformation into a concrete resettlement zone for Tibetans displaced by industrial development projects, 2014.

From 2011 to 2014 I documented the construction of a series of massive dams on the upper Mekong, where it descends from the Tibetan plateau. The Huangdeng, Tuoba, Lidi, and Wunonglong dams were being built to generate electricity to power cities in eastern China. Roads, bridges, and scaffoldings were underway, but these were like industrial chaff that did not diminish the majesty of the mountains and the river, and life seemed to continue as it had for centuries. Whitewashed villages speckled the olive and rust-colored valley walls above the river. I traveled freely, and walked directly through the construction sites as I photographed them.

By 2019, everything had changed when I returned to document the completed dams and their effects on local communities and ecosystems. I drove a rented motorcycle up and down the river for three days, photographing these geometric leviathans looming hundreds of feet above the landscape, like aliens from a robot world. Mountains had been raked apart for stone to crush into gravel. The upper Mekong had been transformed from a muscular, churning roil, flashing bronze and silver in the sun, to a bloated, muddy series of reservoirs, elongated puddles that reminded me of drowned worms.

After photographing the dams, I rode further north to Cizong, a Tibetan village that had been a self-contained, traditional community in my previous visits. Cizong was famous for its home-made wine – a French priest established a church there and planted a small vineyard in the early 20th century, and a hundred years later Tibetan families were still cultivating grapes and fermenting them in huge vats.

Home-made grape wine for sale next to a gravel crusher in a Tibetan area on the upper Mekong, 2011. Photo by Scott Ezell.

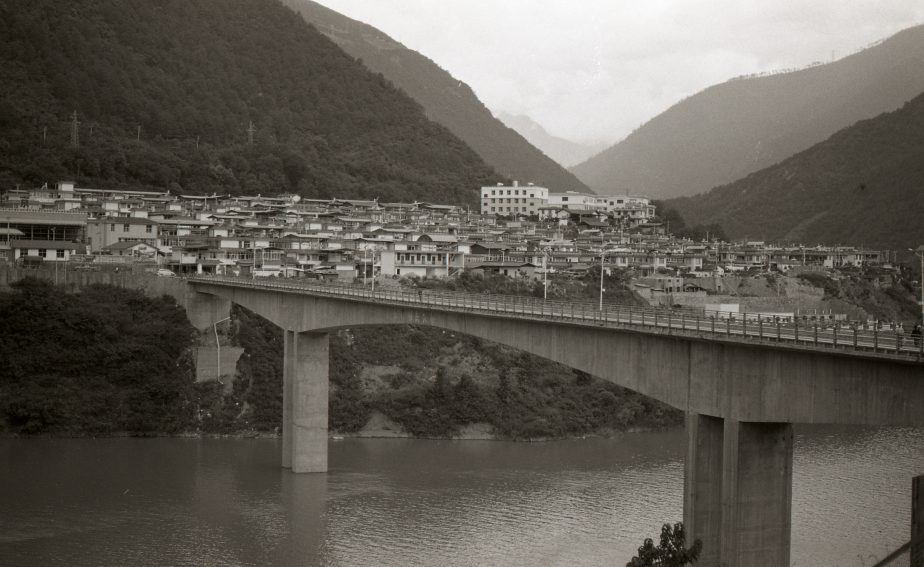

But in 2019, Cizong had been turned into a resettlement zone where thousands of displaced Tibetans were concentrated in a ghetto of barracks-like buildings, hundreds of feet long and divided into apartments. The grape fields were gone, paved over, and built upon. There was no land for the new residents to plant gardens or keep animals, just a dense grid of buildings divided by narrow lanes piled with rubble. This and other resettlement zones I saw lacked any vestige of the space, freedom of movement, and autonomy that always defined Tibet in my experience.

I was invited to a Tibetan wedding in Cizong. It was a festive affair, with dancing and singing and attendees wearing ornately brocaded wool tunics. But even here the people spoke warily of their dependence on “government rice,” stressed by having no work and no land of their own. They had become dependents of the state that had displaced them and was tearing up the earth beneath their feet.

When I returned to Weideng, the town where I’d rented the motorcycle, a SWAT team was waiting for me. I was questioned in the police precinct, but since I was shooting with a film camera they couldn’t see that I’d been trying to capture the destructiveness of the industrial projects metastasizing around us. The police expelled me from the area “for my own safety,” claiming that this was a dangerous area full of alcoholic minority people who were prone to aggression against outsiders.

To the contrary, the Tibetan people are the most generous and hospitable I’ve met, and I could hardly pass by anyone in this region without being offered whatever they had to give – walnuts, peaches, butter tea, cans of beer, invitations to eat and stay in their homes.

In the police station, I was puzzled that no one checked my passport, until I saw two officers holding a print-out of it in their hands. They’d accessed it from a database using facial recognition software, and didn’t even have to ask my name.

Hundreds of miles north, another form of land-grab and cultural assimilation was in progress. When I visited the market town of Yushu in 2004, it seemed almost pre-industrial in its slow rhythm, outdoor markets, and horse-drawn wagons. But a 6.9-magnitude earthquake struck Yushu in 2010, killing thousands and destroying the town’s traditional buildings. PLA soldiers were deployed from Xining, the capital of Qinghai province, to help with relief efforts, but then were never withdrawn. Their presence became a kind of disaster occupation – a variation on “disaster capitalism” – in which rescue and rebuilding were a means to remake the town according to the terms of Chinese authority.

Traditional architecture was replaced with quadrilinear high-rises and rows of identical dwellings like low-end tract homes, to the point that Yushu no longer resembles a Tibetan town. Like the Tibetan communities displaced by the upper Mekong dams, the residents of Yushu were provided government housing, but in the form of cheap concrete boxes with no relation to Tibetan function and design, and no vestige of the autonomy and tradition residents had been forced to give up.

This was an ethnocide that didn’t even require relocating or eradicating a people, only squeezing, dissolving, undermining their identity and way of being, until they were no longer home, though they had never left.

A resettlement zone on the upper Mekong for Tibetans displaced from their land by dams, 2019. Photo by Scott Ezell.

These anecdotes of personal experience are part of a broad pattern of the Chinese state imposing ethnic, cultural, and economic hegemony on Tibet and other minority areas. These policies continue today, and Tibetan writers, activists, and monks, as well as ordinary citizens remain at risk of being imprisoned, tortured, and killed, within a national context of black jails.

In neighboring countries, China implements the same top-down model of industrial development as those I witnessed in Tibet – I have watched Chinese dams, plantation agriculture, and mining projects proliferate in Laos and Myanmar, with the complicity of local elites and with the same destructive effects on local communities and landscapes.

Western democracies rightly condemn China’s human rights and ecological record in Tibet and elsewhere. Unfortunately they have little moral authority, considering that they support equally repressive regimes elsewhere, and profit from hundreds of billions of dollars in annual trade with China, as well as carrying out their own forms of occupation and violence.

China’s policies in Tibet take place within a larger global system predicated on exploiting the cheapest sources of labor and materials, without taking into account the costs or consequences of disenfranchising Indigenous peoples and ravaging their lands. Because every major state and corporate entity today is based on this system of exploitation, top-down approaches to ecological or humanitarian issues are often ineffective, if not outright boondoggles, maintaining the status quo they purport to address.

An ethnic Han Chinese worker at a road construction site in eastern Tibet, 2011. Photo by Scott Ezell.

Healthy human communities are necessary to maintain healthy ecosystems, and returning Tibetan lands to the stewardship of Tibetans who have practiced sustainable land management for centuries is the only way to preserve their vulnerable landscapes and communities. While it is not unique in being a threatened ecosystem and culture, Tibet has singular significance as the world’s “third pole,” holding the largest amount of frozen freshwater outside the North and South Poles. Tibet has been called the “watertower of Asia,” and 2 billion people depend on ten major rivers originating on the Tibetan Plateau.

As one of the more publicized Indigenous territories under threat in the world, Tibet serves as a conspicuous example of the effects of state violence against a living set of human and natural relationships.

My recent book about eastern Tibet ends with an image of blue ink, blue rivers, and blue oceans, and a connection between all three as symbols of regeneration, cyclicity, and freedom. It has become a truism of our time that it’s easier to imagine the end of the world than the end of capitalism. Considering the global challenges we collectively face today, it would be a good beginning to imagine a world in which the affluence and subsistence of one society is not based on the destruction of another – in Tibet and throughout the world.