Sitting in my university office in Paris, I was recently visited by a young French student wishing to learn the Urdu script. He had traveled to Turkey to study Indian Sufism, and his teachers had told him that learning to read Urdu was an essential first step on that path. It was another reminder of how the script preserves vital links to the past despite ongoing threats to its future.

In India, Urdu holds a prestigious position as one of 22 official languages recognized in the constitution. However, its unique Perso-Arabic script remains threatened by frequent calls for its abolition. Commentators and campaigners have long argued that replacing the Urdu script with either the Latin or Devanagari alphabets (used for English and Hindi, respectively) would forge links between different communities and promote communal harmony.

But despite being sometimes couched in talk of unity and progress, those calls are part of the ongoing “war on Urdu” in India. Replacing the Urdu script would do irreparable damage to the language and the links that it promotes with the exceptionally rich and complex culture of the subcontinent. To understand the threat that Urdu script faces and the importance of preserving it, it is necessary to look back at its history and forward at what its future might hold.

The History of Urdu Script in India

The French font designer Ladislas Mandel once wrote that “a letter is not only a mere sound, it is the trace of mankind.” Indeed, script is one of humanity’s engineering marvels, and the development of the first writing system in ancient Sumeria around 5,300 years ago can be considered the dawn of history, allowing the spoken word to be set, sometimes literally, in stone. In the millennia that followed, hundreds of different scripts were developed, and around 300 of them are still in use today.

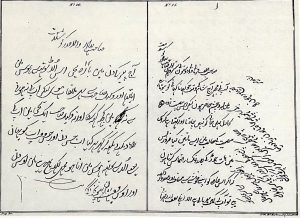

The Urdu script draws heavily on the Perso-Arabic script that developed in Persia after Islamization, but it also carries influences from Sanskrit. It spread into the areas that correspond to modern Pakistan and northern India, where it went on to play a major role in both the Muslim and the Hindu cultures of the region.

The famous devotional ghazal poetry of Muslim writers such as Mirza Ghalib, Muhammad Iqbal, and Faiz Ahmad Faiz is unimaginable without the Urdu script. However, what is less well known is that the first poems on the Hindu festival Holi were also composed in that same script (by Makhdum Khadim in the 16th century).

Historical Threats to the Urdu Script

Nevertheless, despite such eminence, the status of Urdu, and its unique script, has long been threatened in India. The celebrated 19th-century Hindi poet Bhartendu Harischchandra called Urdu “the language of dancing girls and prostitutes,” an insult that endures to this day on the lips of anti-Urdu activists.

In the early 20th century, calls for the abolition of the Urdu script came from some surprising sources, including such literary giants as Saadat Hassan Manto and Ismat Chughtai. Despite their literary fame being dependent upon the Urdu script they used, both writers’ affiliations with the Marxist-influenced literary progressive movement led them to believe that conversion to the Latin alphabet was essential for the language’s future.

Perhaps they were also influenced by similar reforms that took place in the 20th century, most notably Ataturk’s Latinization of the Turkish language in 1928, which rendered the whole population illiterate for a decade and erased 600 years of cultural and linguistic heritage in the blink of an eye.

Around the same time, 131 communist delegates at the Soviet Union’s Baku Turcological Congress voted to impose the Latin alphabet on the languages of over 50 ethnic minority populations living between Azerbaijan and the Arctic. That decision would have sparked mass illiteracy, deprived the region’s many Muslims of their connections with the Quran, and, according to French journalist Xavier Montéhard, brought about the downfall of the Soviet Union.

Nevertheless, despite the pressure placed on traditional scripts by modernization movements in the 20th century, Urdu’s script was championed by such towering figures of Indian history as Mahatma Gandhi. Urdu’s esteemed place in Indian culture was recognized in the country’s 1949 constitution.

Modern Threats to the Urdu Script

However, neither constitutional protection nor the evidence of the damage done by abolishing scripts elsewhere have stopped calls for the abolition of the Urdu script. Now that pressure appears to be coming from two very different directions: young Urdu speakers and Hindu nationalists.

The former group is showing increasing disenchantment with the script of their mother tongue in favor of using Roman Urdu on many social media platforms. However, the latter group poses a more nefarious threat, perpetuating the false belief that Hindi and Urdu are the same language and arguing that Urdu should abandon its script in favor of Devanagari, used for Hindi.

Proponents of such positions in India argue that the Urdu script is foreign, fraudulent, and restricted to Muslim culture. Moreover, Pakistan, the bête noire of Hindi chauvinists, has adopted Urdu with its script as its national language.

But what would happen if such calls were to be heeded and the Urdu script formally replaced by an alternative? The historical evidence from Turkey and the Soviet Union suggests that the effect on literacy and culture would be devastating.

More recently, academics Shaira Narmatova and Mekhribon Abdurakhmanova have shown how Uzbekistan’s decision to shift from the Cyrillic to the Latin alphabet in 1993 led to a significant decline in literacy among young people. Meanwhile, the winner of the 2022 Sahitya Akademy prize for Urdu literature, Dr. Anees Ashfaq, has argued that the Urdu language will die if its script is converted.

So, what can be done to save the Urdu script and the centuries of cultural knowledge that it contains?

Saving the Urdu Script

The threats Urdu faces are different in source and nature, but the remedy to them all is the same: cultivating an understanding of the unique value of the Urdu script and the precious role that it plays in Indian, and global, culture.

The first element of the script’s value is the perfect fit that it has with spoken Urdu. The Devanagari script used for Hindi is not suitable for the Urdu consonantal system. For example, many Urdu consonants have no equivalents in Devanagari, like khe خ , zal ذ , ze ز , zhe ژ , ghayn غ , qaf ق .

Similar problems exist when trying to represent spoken Urdu in the Roman alphabet. Indeed, the Urdu lexicographer Rauf Parekh asked how the Roman alphabet can be used to write Urdu or any other language when it does not even represent all sounds that occur in English.

No script developed for another language can truly represent spoken Urdu. Any shift to another script would cause much of the vocabulary of Urdu to be lost, meaning its literary heritage would not be understood by the coming generation.

Any script is a precious reflection of human civilization and erasing any would also wipe out a part of our rich global heritage. But the loss of the Urdu script would be particularly acute because the Urdu script opens a window to a vast part of Indian culture.

So, the attempt to preserve Urdu must emphasize its long and proud history on the subcontinent and how it is intertwined with both the Hindu and Muslim cultures of the region. Trying to represent its words with another alphabet would be like deconstructing the Taj Mahal and rebuilding it with different bricks; some surface similarities might remain but the building would no longer be the same.

India is a country whose wonderful diversity stems from the richness of its past. Attempts to forcibly cut out elements of that diversity would sever our links with our past, with grave consequences for our future. The more that people perpetuate myths that erase elements of Indian history, the more they cultivate the attitude that certain scripts, languages, cultures, and peoples do not belong in India.

The preservation of the Urdu script is an essential intellectual endeavor for Indian social democracy. It is no exaggeration to say that our cultural diversity depends upon it.