The Netherlands feels increasingly squeezed in the “extreme competition” between the United States and China, and has reached out to South Korea to mitigate part of its fallout.

Although they share some of the same apprehensions vis-à-vis Xi’s China, neither wants to be dragged into the U.S. fight to sustain liberal primacy as a fully aligned participant.

In a joint report by the Dutch intelligence services in late November, dire warnings were cast about China’s asymmetrical challenge. Labeling China as the “biggest threat to Dutch knowledge security,” the report stated, “Dutch businesses, knowledge institutions, and scientists are widely targeted by various (digital) attack campaigns attempting to capture high-value technology.”

Ten days before that, however, the Dutch Minister for Foreign Trade had issued a bold statement directed at the United States, saying the Netherlands limits exports of ASML, the world’s leader in lithography systems, to China “on [its] own terms.”

In 2019, after severe pressure from the Trump administration, the Netherlands banned ASML from exporting its extreme ultraviolet (EUV) lithography systems to China. These machines can produce the most advanced chips needed in, for example, artificial intelligence. EUV sales constitute half of ASML’s revenue.

These two competing pressures are a testament to the predicament the Netherlands finds itself in. The international system is undergoing profound structural change, especially impacting the semiconductor field. Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company’s founder, Morris Chang, recently lamented that globalization and free trade are “almost dead.”

As is common in times of great transformation, smaller states are seeking new alignments to offset vulnerabilities beyond their control. In the emerging new cold war, these efforts are all about creating supply lines more resilient to the whims of geopolitics.

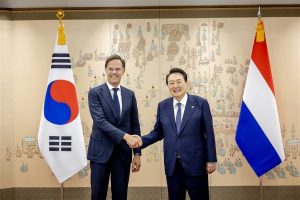

It is in this context that South Korean President Yoon Suk-yeol and Dutch Prime Minister Mark Rutte issued a joint statement on November 17 in Seoul, establishing a strategic partnership.

At the heart of the statement lies the call for greater cooperation between both countries’ public and private sectors to “jointly protect and promote critical and emerging technologies.”

Looking at the timeline, the impetus for elevating bilateral relations is obvious.

The U.S. Bureau of Industry and Security issued a one-year licensing waiver in October for Samsung and SK hynix to export chips to China. The two South Korean conglomerates operate high-end factories in China that use U.S. chip equipment and designs, bringing them under the ambit of U.S. export controls. One estimate puts the share of Samsung’s chip sales revenues that are earned in China at 25 percent; for SK hynix, that share is valued at 40 percent.

Earlier, in September, South Korea was not on board with a U.S.-proposed coordination platform called the “Chips 4 Alliance,” with Japan and Taiwan, out of fear of Chinese retaliation.

Indeed, it is not in South Korea’s interest to disrupt the current optimal ecosystem, something that was echoed in November by Dutch NXP and other European mature-node chipmakers. China is a crucial hub for the manufacturing of these kinds of semiconductors, which are used in cars and home appliances as well as for the production of key parts and materials.

Of course, it was the shortage of this segment of chips in 2020 that led to the rethink of existing supply lines in the first place. That said, a full reshoring or “friend-shoring” of production capacity that uses larger, older nodes is not feasible economically.

Toward the EU’s quest to obtain “digital sovereignty,” a logical next step in the new Netherlands-South Korea partnership could be a high-end South Korean plant in Brainport Eindhoven.

A tech hub situated less than three miles from ASML, the plant could in exchange be given preferential access to operate ASML’s newest EUV systems there. Samsung would be able to leapfrog the currently most advanced 3-nanometer process and commence with the production of the newest 2-nanometer-based chips in Eindhoven. The Netherlands’ $21 billion National Growth Fund could facilitate this initiative.

For both countries, the competition in the semiconductor sector is fierce. Taiwanese TSMC has already been swayed to build chip plants in southwestern Japan (with the Japanese government investing in a 50 percent stake) and in Arizona. Following the United States’ CHIPS and Science Act, offering vast subsidies, TSMC announced in December that it is building a second plant there and increasing its commitment to $40 billion.

Industrial policy is back, and it is front and center in today’s geopolitics. For the Netherlands, which has an open economy deeply intertwined with German manufacturing, a South Korean plant would go a long way in mitigating supply uncertainties. Besides the machines that make the chips, South Korea could diversify its export and gain closer access to the EU, the world’s largest single market.