The news that China’s population shrank in 2022 caused a sensation. Despite it being a relatively modest drop of around 850,000 (or a loss of 0.6 per thousand), many articles not only expressed shock, but also proposed dramatic assessments of the consequences on both the Chinese and global economy.

The sensationalism that accompanied reports of China’s declining population demonstrates a lack of understanding of China and the world’s demographic trends. Indeed, the fact that China’s massive population was going to inevitably decline was already well-known; the United Nations’ Department of Economic and Social Affairs projected last year that population decline would begin in 2023. DESA also forecasted that the total population of the planet will start declining in around 60 years, so China is far from an outlier in this regard.

What in fact makes China different with respect to other countries, especially those that were in a similar socioeconomic situation immediately after World War II, is the speed with which its fertility has declined. And while many analysts might blame the longstanding one-child policy for that, the data suggests otherwise.

Figure 1 shows that, contrary to the prevailing narrative, the most substantial fall in the total fertility rate (TFR), that is the average number of children per woman, occurred between 1965 and 1980, i.e., before the introduction of the one-child policy. In those 15 years, China’s TFR fell from 6.56 children per woman to 2.87. It would then fall under the replacement fertility rate of 2.1 in the early 1990s, thus aligning China with the average values recorded in high-income countries (HICs).

As a matter of fact, China’s population trajectory is analogous to those of the most developed countries. It has been known for a long time that the demographic transition has broadly the same demographic consequences in all countries, as it always triggers a three-phase process: In the first phase a population increases at increasing rates, in the second it increases at decreasing rates, and in the third it declines. Therefore, it is appropriate to abandon the idea of China as a unique case (which, unlike the West’s exceptionality, almost always has a derogatory connotation) and analyze what is happening in countries already in a similar demographic situation.

According to some commentators who believe there is a direct relationship between demographic and economic trends, China’s population decline will trigger an economic crisis that will impact the global economy. However, recent works instead show that the relationship between population and economic growth is negative, which was actually the prevailing opinion until the early 1980s. Already in the 1930s, in response to John Maynard Keynes’ position that demographic decline leads to a decrease in aggregate demand, Polish economist Michał Kalecki (an unsung hero of macroeconomics) argued to the contrary: “What is important… is not an increase in the population but an increase in purchasing power. An increase in the number of paupers does not enlarge the market.”

Additionally, the hope of a demographic dividend, which assumes a direct relationship between demographic and economic growth, is not in line with reality. Poor countries are in fact facing educational and employment challenges that are far beyond their possibilities.

To correctly understand the impact of the demographic transition, keep in mind that it generates a specific transition in each age group: first in the young, then in the working age population, and finally in the elderly. Consequently, each age group goes through a phase of growth at increasing rates, a phase of growth at decreasing rates, and then a phase of decline.

Over the past 250 years, the nearly 200 countries on our planet began to walk down the path of the demographic transition at different moments in time, as they reached a certain level of modernization, so that now they are now distributed in a long line along the same path..

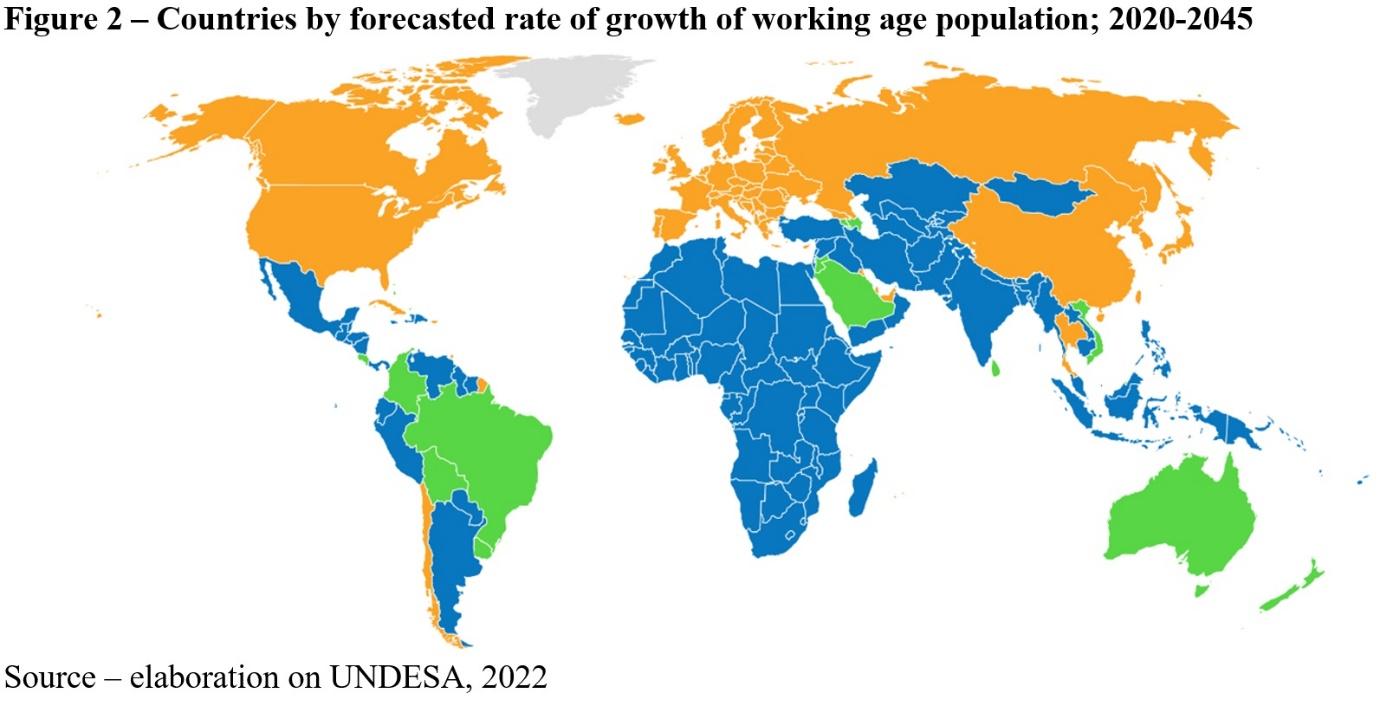

Figure 2 simplifies this situation by dividing the world’s countries in three groups: 1) in orange, a group of mostly developed countries (including China), characterized by a declining working age population; 2) in blue, a group of developing countries in which the working age population is exploding; 3) in green, a smaller group of countries in an intermediate position.

It is realistic to assume that in the countries in the first group – including China – the labor force will necessarily decline once the participation rate has reached its physiological maximum. This will result in a structural labor shortage, the actual amount of which will depend on the interaction between the demographic sphere (which determines the reduction of the labor force) and the economic sphere (which determines the variation in the level of employment).

In conclusion, there are no obvious reasons why a fall in population will inevitably lead to a fall in production. That said, it is also true that the demographic transition creates the preconditions for the emergence of a structural shortage of labor that could lead to a fall in production. In practice, however, this has not been the case in the countries that have already found themselves in this situation, as well documented by European Union data.

EU countries were the first to be affected by the demographic transition, and their working age populations started to decline at the beginning of the 21st century. Over the 1995-2020 period, the EU’s working age population was affected by a natural decline of 20.6 million (-6.4 percent), which was, however, more than offset by a migration balance of 26.2 million (a little more than 1 million per year). As a result, the working age population increased by 5.6 million, from 323.2 to 328.8 million. (Table 1). Since employment increased by 33 million, the rate of employment surged from 61.5 percent in 1995 to 70.5 percent in 2020. In conclusion, EU countries confronted the decline in labor supply produced by the demographic transition resorting to a higher rate of employment and (at times illegal) immigration.

Since 2013, China also finds itself with a declining working age population. Chinese economists and politicians, however, have long argued that the resulting decline in labor supply may be confronted by increasing productivity made possible by AI and robotization.

I have argued in previous works that while it is in Beijing’s interest to implement all active labor policies that could reduce its structural shortage of labor, there are theoretical and empirical reasons to believe that such measures (including technological advancement) will not suffice to bridge the need for foreign workers. Moreover, unlike the EU, China’s rate of employment is already very high, so further contributions by the local labor supply can only be very modest.

While the example given by European countries may be quite instructive, it is also important to note that despite needing millions of migrants, EU member states have tried their best to prevent their arrival by all possible measures, save directly shooting them. These policies have and continue to be ineffective in deterring migrants, come at a huge monetary cost, and, most importantly, have caused the deaths of thousands of men, women, and children.

Since migrants will inevitably go where there is work, the question that Beijing has before itself is simple: either adopt a humane and rational immigration policy or follow the missteps of the EU. This rational policy would consist in co-managing migration flows consistent with China’s labor needs – which I have estimated at around 190 million for the period 2020-2045 – with countries characterized by a structural excess of labor, for instance those with which Beijing already cooperates within the framework of the Belt and Road Initiative. To achieve this, Beijing should assess its qualitative and quantitative labor needs, finance the training of future immigrants in the countries of departure (as a sound economic approach would suggest), and proceed with their transfer and integration into the Chinese labor market.

The alternative is to try to “fight the market” by attempting to prevent the arrival of illegal, but strongly needed, migrants. As the EU example shows, this will be very expensive, leave migration flows in the hands of organized crime, and likely cause the deaths of thousands of people who will do all that is possible to reach China’s vast labor market.

In conclusion, what could cause an economic crisis in China is not the decline of the total population, but rather Beijing’s possible reluctance to resort to immigration, a measure certainly not appreciated by the Chinese population but no more embraced by EU citizens. This would have several consequences. On the economic front, it would result in Chinese and foreign companies not being able to find needed labor force, meaning increasing wage pressure. More broadly, a restrictive immigration policy would cause a growing number of migrant deaths, which would tarnish Beijing’s image in the Global South. Finally, it would prevent China’s global rise.

Beijing has historically been pragmatic, and its institutional characteristics could make it more able to confront public opposition to migration. Considering the importance that economic growth plays in the covenant between the Chinese government and its citizens, one can hope that China will adopt a rational migration policy to avoid the political risks of an economic crisis induced by demographic trends, as done – however unwillingly – by the EU, the United States, and other high-income countries.