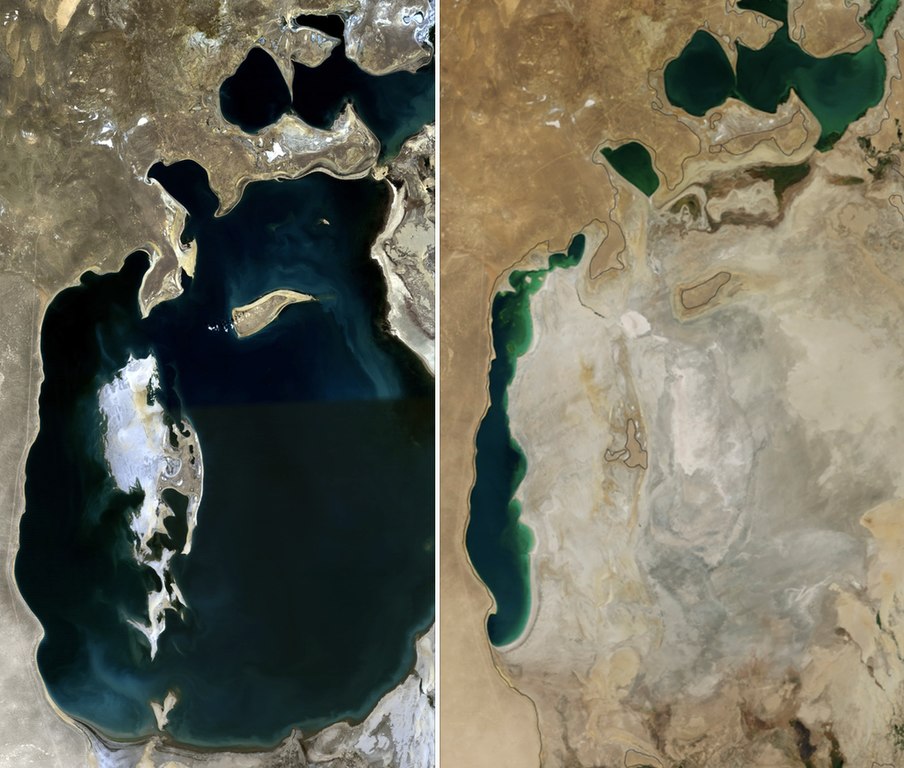

Prior to 1960, the Aral Sea was the fourth largest inland water reservoir in the planet, with a surface area of 66,900 square km. 1960 is a key date because it was the last time that the sea’s water level was stable. Since then, production of cotton, famously referred to as “white gold” due to its economic importance in the Central Asia region, increased dramatically, and so did the demand for water. Irrigation accounts for 92 percent of aggregate water withdrawals since 1960.

Climate change hasn’t helped either. Shrinking glaciers and snowfields in the Tian Shan mountains and Pamirs are expected to diminish the water inflow into the Aral Sea even further.

Projects aiming to address desiccation have had mixed results in the past. For example, the massive capture and re-channeling of the Syr Darya project completed in 2005 by the World Bank and government of Kazakhstan resulted in the stabilization of the water balance in the North Aral Sea between 2005-2011. Any improvements in water restoration have been, nevertheless, short-lived and countless initiatives have failed given the complexity of the hydrological system of the basin.

The Aral Sea in 1989 (left) and 2014 (right), as viewed in NASA satellite imagery. Photo collage via Wikimedia Commons.

Investors seems to have given up on these large-scale, cross-border and costly projects. Some schemes are still underway but they are less ambitious and their implementation is still unclear.USAID recently launched a Regional Water and Vulnerable Environment Activity 2021-2024 worth $1.35 million focused on small innovative projects across the basin. Surprisingly, the European Investment Bank announced in 2019 that it was preparing to invest 100 million euros on Aral Sea restoration projects in Uzbekistan, but the project has been delayed and plans for its implementation remain unclear.

Despite countless (failed) attempts to restore the Aral Sea, much of the region continues to suffer from extreme environmental degradation and the social and economic repercussions that follow. Forty million people live in the Aral Sea basin and are exposed to life-threatening consequences of the sea’s desiccation.

A key public health issue surrounding the desiccation of the Aral Sea is the eminent health concern that this can cause as salts, heavy metals, and chemical toxins in the air and water affect bodies. Contamination from the industrial sector is created through the discharge of poisonous residues into rivers and into the air, leading to severe cases of poisoning and chronic respiratory illnesses. A recent study found that people living in the areas closest to the Aral Sea have higher rates of cardiovascular diseases as well as psychological disabilities. Furthermore, data from local oncology dispensaries in the Aral Sea basin between 2004 and 2013 reveal higher rates of malignant neoplasm, which manifest in a multitude of different cancers.

Another increasing public health concern is the possible transmission of diseases coming from the former island of Vozrozhdeniya, a key site for bioweapon testing by the Soviet Union. Although the facilities had been decommissioned, there are concerns that diseases such as anthrax, smallpox, plague, or typhus could become exposed with further desiccation of the former seabed, in which toxic material and infrastructure are stored.

It is highly unlikely that the Aral Sea will dry up completely by the end of the century. However, the area will undoubtedly become hypersaline and of little ecological or economic value. What was once famously described as “one of the planet’s worst environmental disasters” by then-U.N. Secretary General Ban Ki-moon is more than just an ecological disaster; it is a public health emergency. Addressing this crisis should be at the forefront of any future investment in the Aral Sea basin.