The debate about whether South Korea should pursue independent nuclear armaments is once again making headlines. A recent survey showed that nearly 77 percent of South Koreans believe in the necessity of developing a domestic nuclear weapons program. The issue has gained even more traction with major government figures, including the president himself, floating the possibility of South Korea going nuclear.

But this isn’t the first time that Seoul has considered or even pursued a nuclear weapons program. In fact, back in the 1970s, the United States was more concerned about a nuclear program in the South than the North, a scenario that seems unimaginable today.

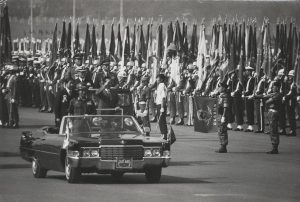

In 1972, South Korean President Park Chung-hee launched a clandestine military nuclear program called “Project 890,” the existence of which was only discovered by Washington in late 1974. This was a period of high anxiety for Park, who had witnessed the murder of his wife by a pro-North Korean assassin in 1974 while also discovering several North Korean infiltration tunnels under the DMZ in 1974-75. Besides this, Park was also displeased with the Nixon administration’s decision in early 1970 to withdraw a U.S. Army division, amounting to 20,000 troops out of the 63,000 stationed in the South at the time.

As seems to be the case now, the South Korean leadership in the 1970s was growing increasingly skeptical of U.S. security guarantees. Despite Seoul’s repeated hardline stance on the issue, however, Washington was able to convince South Korea against going nuclear. With the risks in 2023 higher than ever, it’s worth taking a look back to reflect on what can be learned today from what happened in the 1970s.

Project 890

South Korea’s nuclear ambitions started becoming a major issue in 1974, when U.S. intelligence began gathering increasing evidence of Seoul’s efforts in this area, estimating that if Park’s plans were not stopped, the South could acquire nuclear weapons by 1980.

The United States also discovered that South Korea was negotiating with France to purchase a chemical separation plant, which could be used to produce plutonium from spent reactor fuel. South Korea was also in talks with Canada to buy a nuclear reactor. By November 1974, a French diplomat confirmed that France was indeed considering selling a reprocessing plant to South Korea.

By February 1975, Washington was considering inhibiting South Korean access to sensitive technology and equipment both through unilateral and multilateral coordinated actions. U.S. intelligence at the time showed that, besides nuclear capabilities, South Korea was also looking into ways to improve its missile technology.

One March 1975 telegram from the State Department sent to the U.S. Embassy in Seoul clearly stated that Washington “would not intend to provide technology and/or equipment which we would feel might be harmful to our own interests and the stability of the area.”

Throughout this time, U.S. and French diplomats maintained close communications and cooperation on the issue of the potential sale of the reprocessing plant. In fact, France was willing to accept U.S. requests to call the deal off with South Korea as long as they received “reasonable financial compensation.”

By August 1975, U.S. Ambassador to South Korea Richard Sneider was actively trying to persuade Seoul to call the French deal off, arguing that the best course of action would be the joint exploration of possibilities for a multilateral reprocessing facility. The South Korean side, however, disagreed and said they wanted the French plant as a “learning tool” and reacted with an “expression of surprise” at the ambassador’s remarks.

In fact, Seoul said it had tried to reach out to various U.S. organizations in 1972 for assistance in developing a fuel reprocessing plant, but got no response. As a result, they turned to the French. According to the South Koreans, canceling the French contract would be “impossible” and they instead urged the United States to accept it and conduct inspections as needed. Construction of the plant in Daejon was reportedly already underway in September 1975.

South Korea was also upset at the perceived discriminatory treatment of Washington when it came to Tokyo and Seoul. Given that the Japanese were buying a much larger reprocessing plant from the French, officials in South Korea wondered why Washington was “singling out” Korea. In response, Sneider said Japan “was not on the DMZ.” In the case of South Korea, Washington had to take into account Chinese, Soviet, and North Korean reactions.

Dissuading Seoul

Despite strong opposition from Seoul, Washington stood its ground. With U.S. pressure growing, by December 1975 South Korea sought “concrete information” about possible U.S. nuclear aid if Seoul decided to cancel the reprocessing deal. Washington’s position was that it would be prepared to send U.S. personnel to the South for peaceful nuclear cooperation after South Korea made the decision to cancel the French deal.

Meanwhile, Canada also stepped up its efforts to convince Seoul to cancel the French deal, asking for assurances that the reprocessing plant would not be built; otherwise, Canada could not sell South Korea its reactors. The move ultimately worked, with the two sides signing an agreement in January 1976 in which South Korea assured Canada that “it is not pursuing acquisition of the reprocessing facility.” The sale of a Canadian reactor to South Korea went ahead the next day.

While Park seems to have ended Project 890 by late 1976, research efforts into nuclear proliferation reportedly continued in the following years. In particular, Seoul’s confidence in Washington suffered yet another blow in 1977 when U.S. President Jimmy Carter ordered the withdrawal of nuclear weapons from South Korea along with the 2nd infantry division.

Despite its domestic efforts, however, South Korea’s nuclear ambitions went nowhere. By 1978, the only way for Seoul to acquire a reprocessing plant was to build one, and Washington had already blocked supplier nations from providing such plants to Korea. Needing support from Washington after seizing power in 1980, Chun Doo-hwan scrapped whatever was left of South Korea’s domestic nuclear weapons and missile programs.

The issue seems to have been put to rest in 1981, when the Reagan administration pledged to maintain troop levels in exchange for Chun redirecting nuclear energy research to civilian purposes.

Lessons Learned and What’s at Stake Today

South Korea’s first attempt at going nuclear leaves us with several lessons and warnings. First, if it was impossible for Seoul to secretly pursue a nuclear program in the early 1970s, there would be absolutely no way of doing so now.

Second, although South Korean technology today is far superior to what it had in the 1970s, it would still need support from the international community to develop nuclear weapons. However, with South Korea being a signatory to the Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) and nuclear non-proliferation being established as a firm principle in the international community, going the nuclear path would mean violating legal agreements, which would lead to diplomatic isolation and multilateral backlash from the international community.

Choosing the nuclear option would also greatly damage the South Korea-U.S. alliance. Washington did not support Seoul going nuclear in the 1970s and maintains this stance today. In addition, South Korea would be jeopardizing its nuclear energy industry as well, since many of its reactors rely on U.S. and other foreign licenses to operate.

Besides this, and perhaps most importantly, South Korea going nuclear would make any calls for the denuclearization of the North completely void. This would prolong the Korean War, make diplomacy almost impossible, significantly raise military tensions on the Korean Peninsula, and even possibly lead to a regional (nuclear) arms race.

Such a scenario would be highly unfavorable for all players involved, in both the short- and long-term. South Korea must realize that its highly-trained conventional forces, backed by U.S. conventional military support, are enough to respond to North Korean military provocations. While the current level of U.S. reassurances to the South may be insufficient for many, the answer should not be the pursuit of nuclear weapons.

The best way to deter a North Korean attack is through diplomacy and dialogue with Pyongyang. This is the only way to come to a peaceful solution, to have a chance at arms control in the North, and to get to a place where peaceful coexistence is possible.