February 15, 2023, marks the 2000th day since the start of the ethnic cleansing of the Rohingya.

Although the historical background of the Rohingya crisis is much longer and more complicated, going back to World War II and including previous massacres/exoduses in 1978, 1991-92, 2012, and 2016, it was only in August 2017 that the news hit the global headlines and the story became well-known.

In August 2017, the Kofi Annan Commission (established by Myanmar’s civilian National League of Democracy government to settle the Rohingya problem) prepared its report, a failed compromise. One day later, Myanmar military posts were attacked by the Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army, a guerrilla group operating in the Rakhine region. In their collective response, the Tatmadaw, Myanmar’s army, resorted to the worst retaliation possible.

The Tatmadaw started a brutal campaign against the Rohingya. In the months that followed, more than 700,000 Rohingya fled to Bangladesh as the Tatmadaw committed ethnic cleansing and crimes against humanity, with “genocidal intent.”

For Bangladesh, the crisis meant a new and unprecedented strain. The country has received Rohingya refugees since 1978, but the scale in 2017 was incomparable to previous exoduses. The official Bangladeshi position toward the Rohingya crisis has combined the acceptance of the refugees with the hope that the influx of people would only be temporary.

On the one hand, Bangladesh openly welcomed the repressed group, presenting itself as a “good global citizen.” On the other hand, Dhaka later declared that the Rohingya must return to their origin country as soon as possible, and that it is Myanmar’s obligation to repatriate them while the international community and the United Nations must persuade Naypyidaw to do so. Since this never happened, Bangladesh and its citizens have to live with the consequences of the prolonged stay.

As the religious, cultural, and humanitarian imperative to help oppressed brethren meets the socioeconomic tensions produced by forced immigration on such a scale, it is of vital importance to hear the voices of the Bangladeshi people. As part of the Sinophone Borderlands public opinion survey in Bangladesh in June-August 2022, more than 1,300 Bangladeshi respondents were asked an open-ended question about their perception of the Rohingya people. Respondents were drawn from all regions of Bangladesh and included a representative sample of age groups and genders. The timing of the survey coincided with the fifth anniversary of the brutal Tatmadaw offensive that sent Rohingya refugees fleeing across the border from Myanmar into Bangladesh.

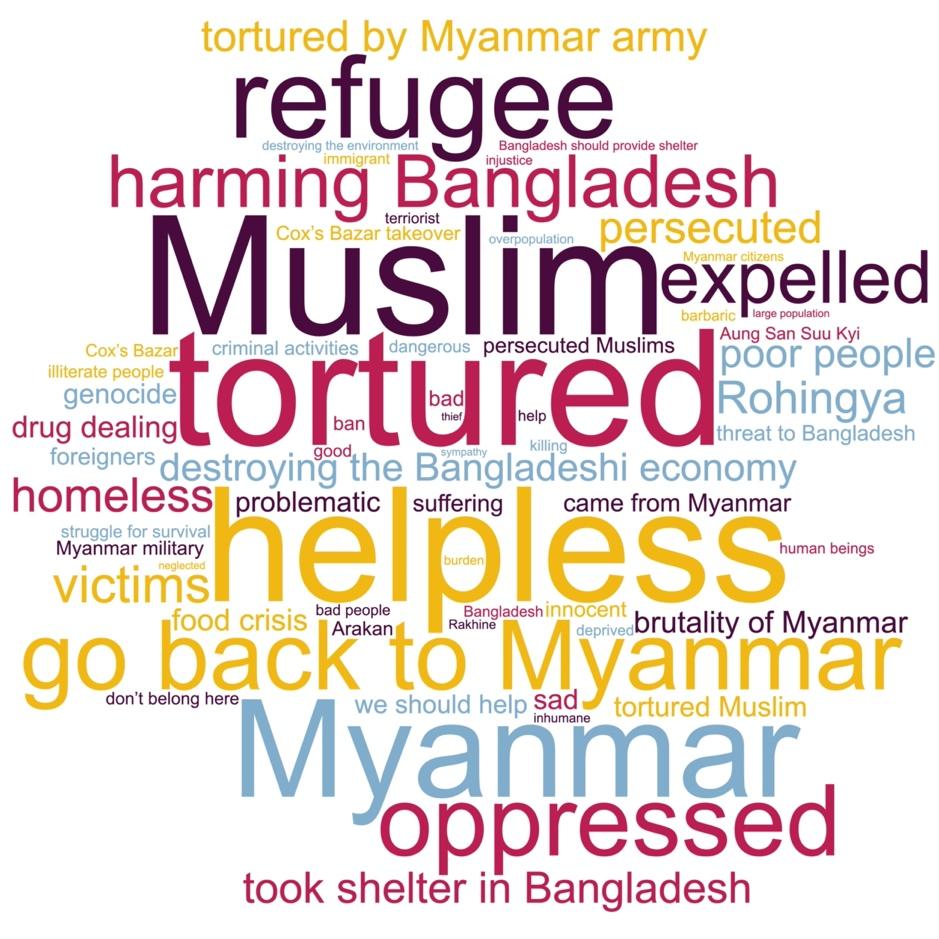

The survey question asked what first came to people’s minds when thinking of the Rohingya. The most common answers, as the word cloud above reveals, were “Muslim,” “tortured,” “helpless,” and “Myanmar.” This gives us a good idea of how Bangladeshis perceive the Rohingya people: as persecuted, helpless, Muslim people originally from Myanmar.

The reason for the Rohingya being in Bangladesh is very clear to Bangladeshis, who provided responses such as “came from Myanmar,” ”tortured by Myanmar army,” or “brutality of Myanmar.” Also, the fact that the Rohingya people are predominantly Muslims is well-known and often highlighted in the responses (“tortured Muslims” or “persecuted Muslims,” for example).

While the Rohingya are seen by many Bangladeshis as persecuted and expelled victims of the Myanmar army and people feel they should help them (see responses such as “expelled,” “victims,” “homeless,” “persecuted,” “neglected,” and “we should help”), there are also voices that see the Rohingya people as a threat (“destroying the Bangladeshi economy” or “harming Bangladesh”) and advocate for sending them back to Myanmar (“go back to Myanmar”). Issues such as drug dealing and a food crisis came up several times. Also, some label the Rohingya as foreigners who don’t belong to Bangladesh.

That said, most Bangladeshis highlight the struggle for survival of the Rohingya people and express sadness over their situation and sympathy toward them.

To conclude, the results of the survey show that among Bangladeshis, empathy toward the Rohingya, the repressed Muslim brothers and sisters, so far trumps tensions and challenges produced by their enforced, prolonged stay. Yet, the longer the Rohingya crisis is unresolved, the more probable a shift toward negative perceptions becomes.