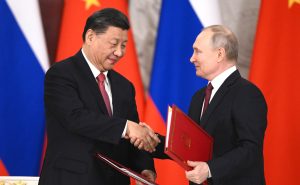

Chinese President Xi Jinping’s first visit to Russia since 2019 was filled with pomp and circumstance: red carpets, horse guards, military bands playing “majestic welcome music.” That’s no surprise, as China has become Moscow’s most important backer in the wake of Russian President Vladimir Putin’s decision to stage a full-on invasion of Ukraine in February 2022.

The ongoing war in Ukraine provided the backdrop for Xi’s visit, which came roughly a month after China issued a formal position paper on its stance toward the conflict. Beijing’s emphasis on a negotiated settlement – and its recent role in brokering a diplomatic breakthrough between Iran and Saudi Arabia – raised speculation that China is looking to take an active role in mediating an end to the Russia-Ukraine war.

But Xi’s time in Moscow makes it abundantly clear that China is mostly interested in talking peace as a fig leaf for engaging more and more deeply with Russia. Xi is not serious about seeking to pressure Moscow into a real peace proposal (which would involve, at the very least, withdrawing Russian troops from Ukrainian soil).

After all, Xi told Putin during their talks that China and Russia “should support each other on issues concerning each other’s core interests.” And he also specifically told reporters that “since last year” – meaning, since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine – “the all-round practical cooperation between China and Russia has yielded fruitful outcomes, and continued to manifest its strengths of solid fundamentals, high complementarity and strong resilience.”

“No matter how the international landscape may change, China will stay committed to advancing China-Russia comprehensive strategic partnership of coordination for the new era,” Xi declared. Chinese officials have made that statement numerous times since the invasion, and it effectively nullifies any potential for China to be a serious mediator. Beijing may have leverage over Russia, but it has zero intention of using it to push for peace.

That much was obvious from the China-Russia joint statement on “Deepening the Comprehensive Strategic Partnership of Coordination for the New Era,” issued during Xi’s trip. Interestingly, China and Russia have quietly dropped the “no limits” formulation that appeared in the joint readout following the February 2022 Putin-Xi summit, and has featured in nearly every press clipping on China-Russia relations ever since. But that shouldn’t be read as a downgrading of the relationship; the 2023 joint statement repeats the formula that China-Russia relations are at their “highest level in history.”

Just as in February 2022, the latest joint statement has a heavy emphasis on working together to reshape the global order toward “multipolarization” and away from “hegemony,” essentially a call for diluting U.S. global leadership. China and Russia upheld their unique framings of “democracy” and “human rights,” which allow governments to define those concepts for themselves (and thereby evade any criticism for human rights abuses or authoritarian rule). And, clearly fearful of the possibility of regime change at home or in their near abroad, China and Russia agreed to hold an annual meeting of their ministers of public security and interior affairs, with the expressed purpose of “preventing ‘color revolutions.’”

China and Russia also plan to expand their economic cooperation, including investment and trade. There’s a notable new mention of ensuring the “resilience of industrial and supply chains,” an echo of the United States’ emphasis on the same topic in the context of weaning itself and others off economic dependence on China. Energy cooperation remain the main pillar of their economic relations, but there are also mentions of expanding cooperation in agriculture and the financial sector.

In their separate “Pre-2030 Development Plan on Priorities in China-Russia Economic Cooperation,” China and Russia specifically stressed ensuring “long-term and mutually beneficial” supply chain cooperation in metallurgy, mineral resources, fertilizers, and agriculture “to ensure food security.” They also pledged to improve cross-border logistics. Sino-Russian trade has become more important for Russia as it faces stringent sanctions from the West, and China is keen to seize the opportunity to expand trade and investment ties for the long haul.

The main joint statement ends with a lengthy discussion of global hotspots, starting with the “crisis” – never a “war” in Chinese or Russian statements – in Ukraine. The statement said that Russia “welcomes China’s willingness to play an active role in resolving the Ukraine crisis through political and diplomatic means,” a sentiment also repeated in the separate readouts of Xi’s meetings with Putin. But this is by no means a serious step toward peace.

For starters, the repeated insistence that “no country should achieve its own security at the expense of the security of other countries” is darkly laughable in the context of Russia literally invading another country in an attempt to ensure its own security from a nebulous future threat. Likewise, the statement is predictably far more concerned with criticizing those who “add fuel to the flames” and “prolong the war” – a reference to the U.S. and European states providing arms for Ukraine to defend its territory – than promoting a Russian withdrawal.

In that sense, China’s position on Ukraine has not changed meaningfully since the start of the war. But it is notable that the topic is now a major part of the public statements following Sino-Russian meetings. In contrast to a previous meeting with Putin where Xi didn’t even mention Ukraine – at least not according to public releases – it was clearly a focus of his conversations in Russia. Rather than ignoring the crisis, China is trying to position itself as a peacemaker.

However, it will be far more difficult for China to replicate the successful Iran-Saudi Arabia deal by mediating between Russia and Ukraine. For one, as Guy Burton pointed out in his analysis for The Diplomat, the Iran-Saudi agreement “highlights the extent to which Chinese participation required a process to already be in place.” Iraq and Oman had already done much of the heavy lifting – arranging initial talks and mediating in the early stages – before China stepped in to see the agreement over the finish line. In this case, China would be starting from scratch.

Second, China’s success in negotiating between Iran and Saudi Arabia was due to its leverage, especially over Iran. Beijing is one of Tehran’s most important global partners; that means Iran has a clear vested interest in keeping Beijing happy. “[T]he fundamental reason why China could finish off the job of meditating between Saudi Arabia and Iran is that China has a bigger impact on Iran than other countries,” Mu Chunshan argued.

China does not have that sort of influence over Ukraine, which is supported at the moment by Western powers. In fact, Xi hasn’t even spoken to Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy since Russia’s invasion, although there was much speculation about a first phone call to follow Xi’s Russia trip.

And while Beijing has influence over Russia, China has already made clear that it won’t use it. Xi himself declared openly that “consolidating and developing China-Russia relations well is China’s strategic decision, based on its basic interests and the larger trends of global development.” Xi also made clear that Russia holds “leading position” in China’s diplomacy, adding that the general direction of China strengthening strategic cooperation with Russia is “unswerving.”

Anyone seriously considering China playing a role as peacemaker in Ukraine needs to wrestle with its constant and overt declarations of long-term partnership with Russia, no matter what.