At the dawn of a new political era in Germany, the German population’s growing mistrust of China is a trend with significant implications for the country’s foreign policy.

In the March 2023 edition of the monthly political opinion poll ARD-Deutschlandtrend surveyed Germans were asked to identify their nation’s most trustworthy partners. The results revealed that a vast majority of respondents – 83 percent – do not consider China to be a trustworthy partner, a degree not far short of the levels of mistrust respondents have toward Russia (88 percent). Conversely, 33 percent of respondents view India as a trustworthy partner, while 59 percent believe the United States to be a trustworthy partner – the highest since before the election of President Donald Trump in 2016. Meanwhile, trust in China remains at the all-time low that it reached in 2020.

According to the November 2022 edition of ARD-Deutschlandstrend, which surveyed Germans on their relations with China, about half of the respondents said that they want to decrease economic ties with China, despite it being Germany’s second-largest export market and largest source of imports. This attitude is remarkable from a utility perspective. Additionally, 69 percent of the surveyed Germans view Chinese foreign direct investment as critical, with the Chinese stake in a container terminal in the Port of Hamburg being a hot topic in Germany in late 2022.

The reasons behind this German attitude are revealed in the same November survey, which found 87 percent of respondents expressing a belief that the federal government should avoid becoming economically dependent on non-democratic countries. Moreover, 68 percent of the respondents think that the human rights situation in China should take precedence over German economic interests when dealing with the country. A similar proportion of respondents agreed with the proposition that China threatened world peace.

Recent opinion polls reveal an interesting trend in Germany’s approach to China. While economic interest has traditionally played a major role in Berlin’s dealings with Beijing, it seems that normative and value-based considerations are now becoming more prominent, alongside a politico-strategic angle strongly drawing on security policy. This shift in public sentiment could be a key indicator of where German-China policy may be headed in the years to come.

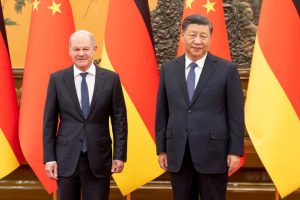

Last year, Chancellor Olaf Scholz declared a political “turning of times,” or Zeitenwende, signaling Germany’s desire to diversify its political and economic ties. However, recent research suggests that German business is not fully on board with this shift. In fact, the country’s economic dependence on China is growing. Imports from China are outpacing exports, and many German industries still rely heavily on Chinese imports.

Indeed, despite the recent shifts in public opinion, German companies seem unwilling to cut back on their China business, even in the face of political pressure. One example is BASF, the world’s largest chemical producer, which recently announced a €10 billion investment in China. According to BASF, the Chinese market accounts for 15 percent of its revenue and 40 percent of the global chemicals market, making the investment a sound business decision.

Germany’s economic connections to China present a complex challenge to its goal of diversifying its global relationships. However, the country’s evolving normative approach to China cannot be dismissed. It is worth noting that the calls from Germany’s comparatively sheltered population to reduce ties with China come at a time when the country’s economy has remained robust and stable, at least in part thanks to its strong economic relationship with China over the last 15 years.

The question remains whether the German population and the German political elite are willing to endure the economic hardships that may result from reducing business ties with China. Only if Germans stay true to their value-based approach to China at the ballot box, even in the face of economic hardship, will the German government have the political leverage to force German enterprises to reduce their exposure to China.

As Germany contemplates how to (partially) fill the potential economic void that would follow reduced economic ties with China, the question looms large: what comes next? While recent high-level state visits suggest that Germany is looking towards Southeast Asia and India, it is important to note that the German public’s trust in India, while higher than in China, also remains relatively low. Furthermore, many countries in Southeast Asia have a history of human rights abuses. Even India’s democracy has faced criticism in recent years, raising questions about how an increasingly values-based approach to foreign policy can be reconciled with deepening ties in these regions.