In the hierarchical structure of the Chinese party-state, lower level cadres with good career prospects always try to avoid being stuck in a post for too long without a meaningful promotion. The rules of elevation are rather vague and competition usually fierce, but one of the most transparent factors is the age constraint. To climb the career ladder successfully, the lower levels have to be passed early enough.

For the most ambitious and fortunate, the coveted provincial-ministerial rank (governors and ministers), which opens a chance for a further national level career, usually has to be attained in their early 50s. Outstanding cadres with aspirations for national leadership get there in their 40s.

The age limits were codified in 1982, at the beginning of the Reform and Opening era, and since then strictly applied. The regulations stipulated the retirement age for provincial-ministerial level top jobs at 65, and for their deputies and all other senior cadres at 60.

In 1997 the customary age requirement of 67 was introduced as the age limit for nominations to the highest national level posts, especially to the Politburo and its Standing Committee. Those age limits were widely regarded by the leadership as a necessity to renovate the party structures in a way that assured stable and predictable generational changes.

But during the preparations conducted by Xi Jinping to extend his rule beyond two terms, the strict and clear regulations became an inconvenient constraint. In September 2022, just before 20th Party Congress and among many more prominent changes, the revised version of the regulations for appointing party cadres got rid of rigidly defined retirement ages and the number of terms in office that are permitted.

As is well known, at the 20th Party Congress, not only was the two-term limit and rule banning new appointments past the age of 68 for national leaders disregarded by Xi Jinping himself, but the newly elected Politburo included two more members that had passed the retirement age. Nevertheless, considering all the nominations that took place at the Congress, there wasn’t any massive departure from past practices on age and term constraints. The difference is that the rules are no longer strictly applied, thus leaving space for all kinds of exceptions and making promotion paths even more vague and uncertain.

The same ambiguity in observing the age constraints applies also to the provincial level leaders. The age and term limits still seem in force, and the latest provincial level nominations confirm that. Half of the provincial party secretaries were changed after the 20th Party Congress, and among the top provincial level jobs (including governors and mayors), there is no official that was nominated before 2020. But among the newly designated, the new party secretary of Guangdong, Huang Kunming, a long-time follower of Xi Jinping, was appointed at the age of nearly 66 – an age suitable for retirement at this level, although he concurrently is also a second term member of the Politburo.

Xi Jinping not only obtained an unusual third term as a supreme party-state leader, but by not hinting at any potential successor he gave the strong signal that he will hold more terms to come. This way, Xi also eliminated the need to look for a successor and groom suitable candidates. Contrary to the previous efforts to prepare in advance for leadership change, now looking for a replacement candidate became not only unnecessary but even undesirable; Xi would prefer to avoid creating any potential challengers.

Rising Stars No More

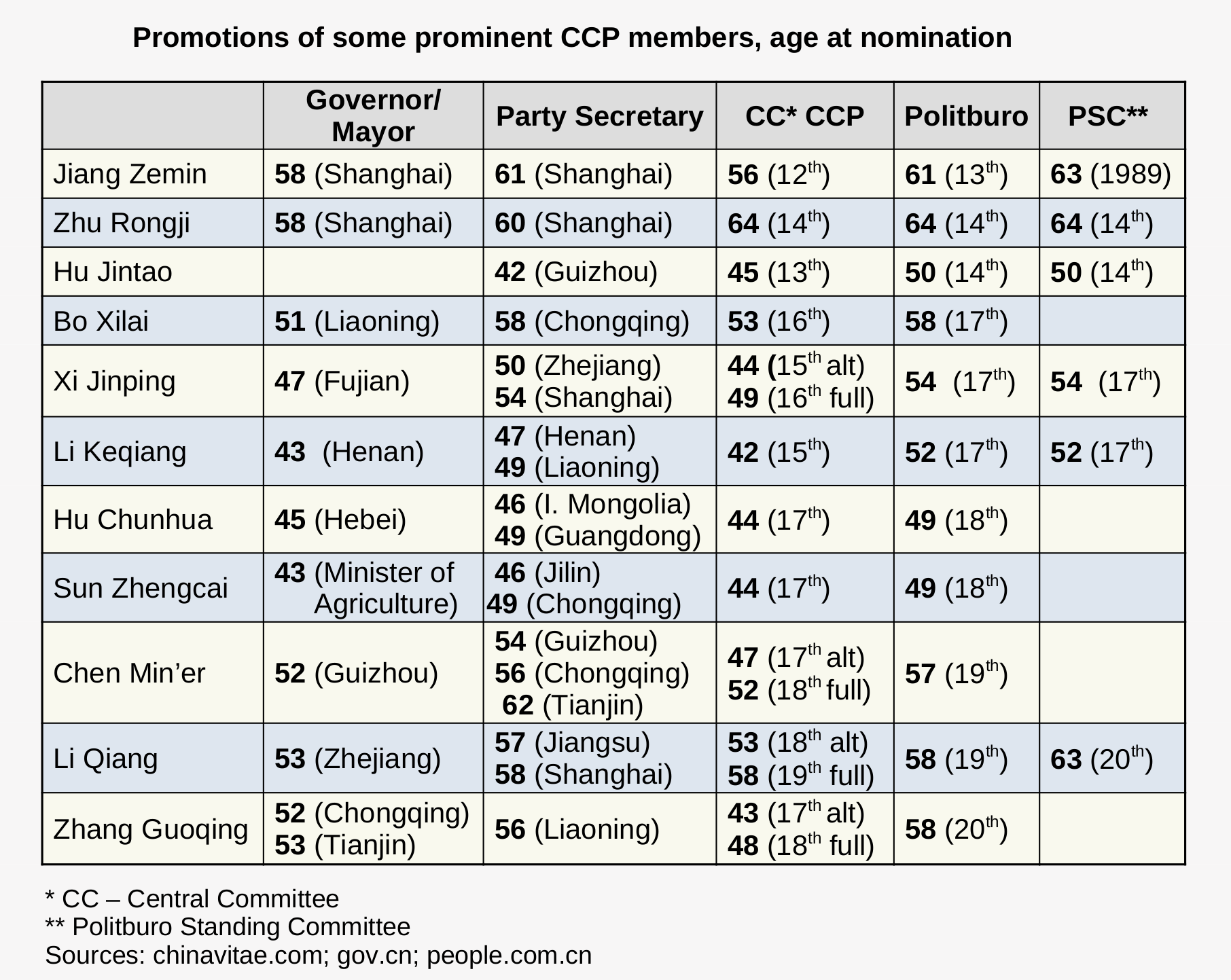

With the highest job out of the race, the whole dynamic of reshuffling posts on the highest levels was inevitably changed. In the past, preparing the future leadership meant placing promising candidates on the fast track of promotions, which meant reaching provincial-ministerial level in their 40s, the Politburo in their late 40s or early 50s, and the Standing Committee of the Politburo at least in their late 50s.

The future leader was supposed to be chosen from among the Standing Committee members to assure the continuity of leadership practices. And the custom of each leader serving two five-year terms at the helm meant that at the start of the second term he should not surpass the age limit of 68. To meet these requirements, a candidate for top leader should get membership in the Standing Committee at the age of 58 or younger, to spend a term learning the ropes before assuming the top job by the age of 63.

The candidates for potential party leaders, with their fast track of promotions, are easily discernible among a cohort of regular cadres. They can become targets for challengers, but the case of Bo Xilai suggests that standing up against a better positioned candidate is a rather daunting task (Bo, in contrast to Xi Jinping, was not a Standing Committee member). Their biggest weakness is vulnerability to factional struggles, since their standings are usually obtained by aligning themselves with powerful superiors.

In the “New Era” of Xi Jinping’s rule, the most obvious example of a career sidelined by factional politics is Hu Chunhua, who was aligned with the rival faction of Premier Li Keqiang. At the 20th Party Congress, Hu was removed from the Politburo (where he had been a member since 2012) at the age of just 59.

His career until 2017 seemed exemplary for a future contender for the highest post: At 44 Hu became a member of the 17th Central Committee in 2007; at 45 he got the provincial-ministerial rank with the nomination for governor of Hebei; at 46 Hu was already the party secretary of Inner Mongolia. Then in 2012, at the age of 49, Hu was elevated to Politburo and later in the same year appointed party secretary of Guangdong, one of the crucial provincial posts.

But under Xi Jinping’s rule, Hu’s ties to Hu Jintao and Li Keqiang became a burden. Even though he became vice premier in 2018, the subtle sign of his sidelining came when he was not elevated to the Standing Committee at the 19th Party Congress. The final blow came last year via his demotion from the Politburo.

The similarly impressive career of Sun Zhengcai came to an even more spectacular end. Sun was demoted from the post of Chongqing party secretary, as well as losing Politburo and party membership, just at the age of 53. He was subsequently tried and imprisoned on corruption charges. A contemporary with Hu Chunhua, they shared the same rapid promotion pace; both were linked with the Hu-Li faction and groomed as their successors before that became a reason to put them out of elite politics altogether.

All Xi’s Men Have Nowhere to Go

But in the Xi Jinping era, it’s not only promising rising stars from rival factions whose careers are being blocked. Even inside Xi’s own support group, the younger members are treated with caution and not allowed the spectacular advancements seen in the past.

Chen Min’er can serve as an example. Working under Xi Jinping in Zhejiang, his national level career started late. In 2012 he became a full member of the Central Committee at the age of 52, and subsequently got the post of Guizhou governor. After two years, he was nominated as party secretary of that province at the age of 54, then, before the 19th Party Congress in 2017 he was assigned as party secretary of Chongqing (a replacement for the demoted Sun Zhengcai). That post is linked with a Politburo seat, which was subsequently given to Chen at the 19th Party Congress. He was 57 at the time, not young if measured by previous standards, though still one of the youngest in the Xi group.

But at the 20th Party Congress in 2022, Chen didn’t make any significant advancements in his career. He wasn’t chosen to the Standing Committee, but instead was shifted from Chongqing to Tianjin party secretary at the age of 62. This way he remains a valuable asset in Xi’s camp, but, at the same time, due to his age, he ceased to be a serious candidate for the highest posts.

Li Qiang, another member of Xi Jinping’s faction, and chosen to become the new premier at next week’s National People’s Congress session, is one year older than Chen Min’er. The two shared the same pace of promotions, with Li getting the post of Zhejiang governor in 2012, and party secretary of Jiangsu in 2016. He became a full member of the Central Committee only in 2017, but simultaneously gained a seat in the Politburo and the post of party secretary in Shanghai, at the age of 58. Then in 2022, then 63, he was elevated to the Standing Committee and destined to head the State Council.

Being always loyal to Xi Jinping, Li was ultimately rewarded with China’s second highest post, but at an advanced age that excludes him from any speculation about being a possible successor. Moreover, he will turn 68 by the next Party Congress, and that makes the next premiership appointment an open question. To continue in the job for a second term, Li will need strong backing from Xi Jinping.

Another example of the new generation of officials faring well in the Xi era is Zhang Guoqing (born in 1964). In his early 50s he won the prestigious posts first of mayor in Chongqing, then mayor in Tianjin, and in his mid-50s he advanced to became a party secretary of Liaoning province. But while this relatively fast-track career earned him a Politburo seat at the 20th Party Congress in 2022, he was already 58 at the time. After being replaced in the party secretary post, he seemingly is being prepared for a high level government job assignment in March. But at the next Congress he will turn 63, and any further advancement in his career would be for one term only.

China’s Top Political Bodies Are Getting Older

The visible reluctance of Xi Jinping to enable and support fast promotion paths even for his own adherents is understandable when taking into account a desire to extend his rule for more terms. Xi intends to block the emergence of possible contenders for power. As a result, there is a tendency in the provincial and national level nominations to give preference to slightly older candidates. That has resulted in a lack of distinctly younger office holders, which contrasts with previous practices aimed at grooming successors.

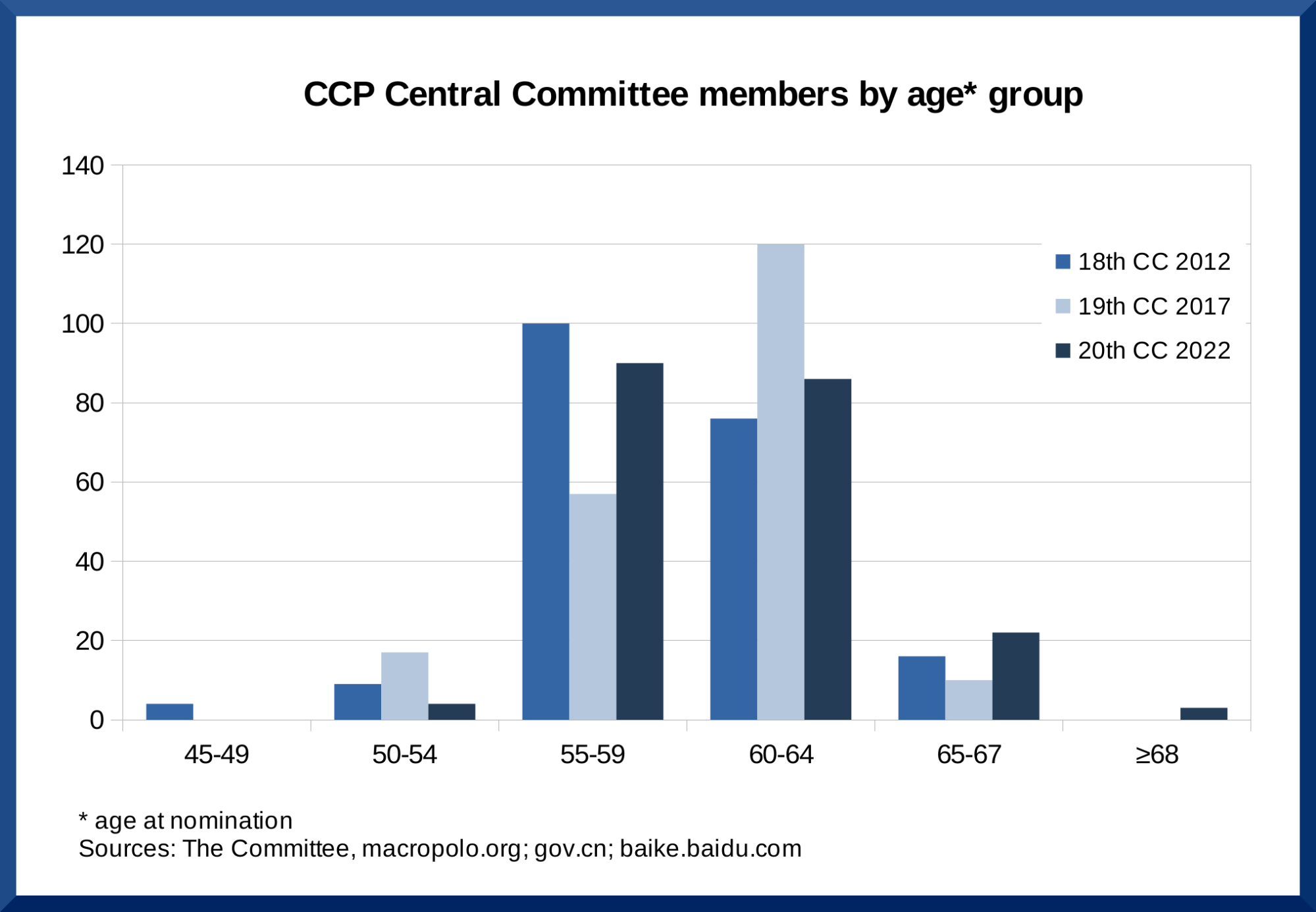

We can see this by comparing the ages of the Central Committee members from the last three terms. The 18th Central Committee, formed at the beginning of Xi’s era in 2012, was least influenced by him. In the 19th and 20th Central Committees (formed in 2017 and 2022, respectively), there were no members in their 40s, whereas in 2012 the youngest member was 45, with three more in that age group. In 2017 the youngest Central Committee member was 50, and 17 members were younger than 55 years old, whereas in 2022 the youngest was 53 and only four were younger than 55.

Moreover, the age limit of 67 at the time of nomination was strictly observed before 2022, when exceptions were made for three members of the Politburo (including Xi Jinping). The current Central Committee also has the highest number of the most senior members, aged 65-67. On the other hand, a high number of Central Committee members in their 60s elected in 2017 resulted in a high number of retirements last year, which enabled more balanced distribution between two core age groups of the late 50s and early 60s in the current Central Committee.

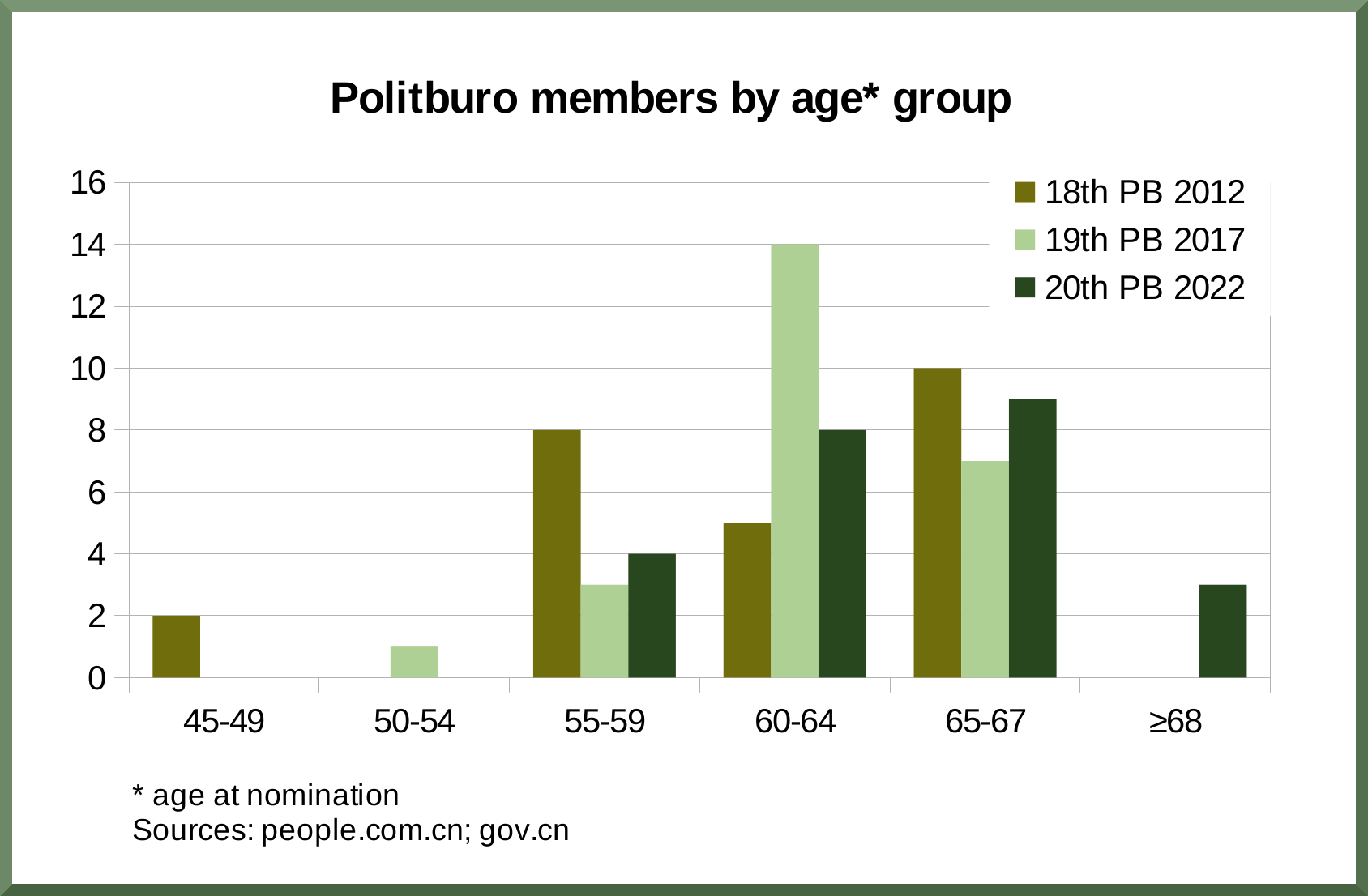

A similar trend is visible in Politburo membership. In 2012 there were two members in their late 40s (Hu Chunhua and Sun Zhengcai); in 2017 the youngest member was 54, whereas in 2022 the youngest is 58. The age limit of 67 was broken in 2022 – not only for two continuing members of the Politburo but also for a newcomer (Wang Yi), which further confirmed the relativity and flexibility of such age limits for those backed by the supreme leader.

But in the Politburo Standing Committee, the only exception to the age limit of 67 was Xi himself, although from 2017 onward, there were no members of Standing Committee younger than 60. In contrast, in 2012 the two youngest members of that supreme body were Xi Jinping and Li Keqiang, both still in their 50s – clearly positioned as leaders-in-training.

The situation among top provincial level cadres (governors and party secretaries) is more complicated, because the nominations and changes don’t need to follow the pace of party congresses, and are usually more frequent. Nevertheless, there is also a visible tendency there to avoid the distinctly younger candidates, especially in their 40s and even in their early 50s.

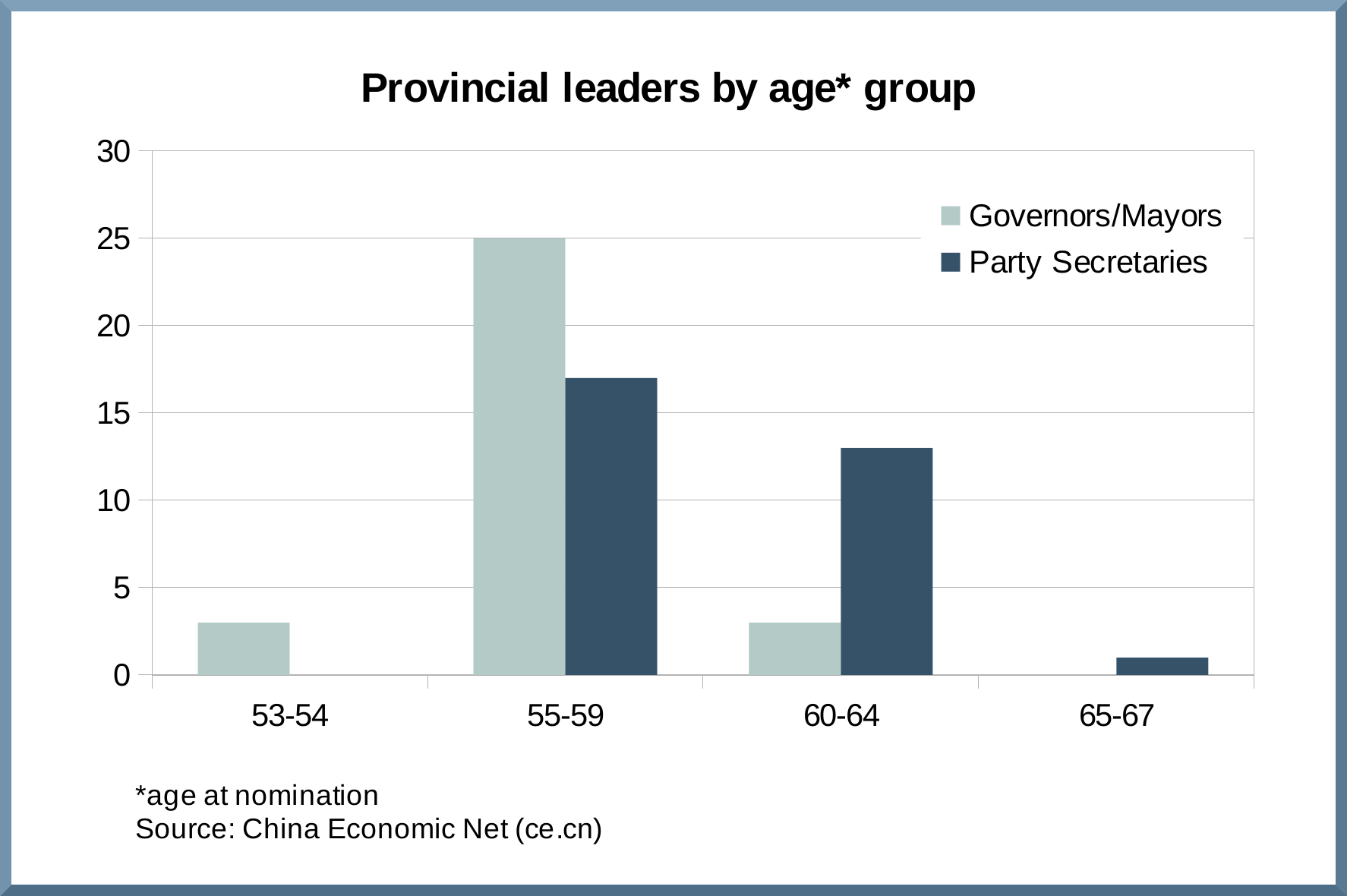

In the group of 31 top administrative entities, including four municipalities, 26 provinces, and five autonomous regions, there isn’t any governor, mayor, or chairman among current office holders that was younger than 53 at the time of their nomination, and no party secretary who was younger than 57 when nominated.

After the 20th Party Congress more than half of provincial-level party secretaries were changed (16 out of 31) and only four governors. Those changes further confirmed the trend of avoiding nominations of distinctly younger officials. Although two of the recently appointed governors are among the youngest in this group – at 53 and 54 respectively – another new government is among the oldest (age 60). Together, amid governor level posts, the overwhelming number of nominations went to cadres in their late 50s (25 out of 31).

The preference for older candidates is especially pronounced when comparing with the past. In 25 of the 31 entities, among the last three office holders there were predecessors in their early 50s, and in five provinces among the last three predecessors were officials in their 40s.

A comparable trend appears among provincial level party secretaries. Three newly appointed ones are, at 57, among the youngest ones, but eight of them are older than 60 – including Huang Kunming of Guangdong, the oldest at nearly 66 at the nomination time. This situation also contrasts with previous practices. Among the last three predecessors of current provincial level party chiefs, there were office holders in their early 50s in 10 provinces, and three entities saw party secretaries in their 40s.

The Political Consequences

The tendency to nominate older cadres for provincial and central leadership posts seems to fit Xi’s intention to abandon the tradition of grooming a successor. It allows him to avoid the creation of potential challengers, impatient enough to start questioning the validity or necessity of breaking term and age rules for the convenience of the supreme leader.

It is difficult to estimate the real impact of those changes for the career paths and motivations of younger cadres, who will have to adjust their plans and desires to the new circumstances. Overall, it is not necessarily damaging for the organizational efficiency of the party apparatus, and at the lower levels the impact can even be hardly noticeable. But with the top leaders getting older, and the long term prospects of power wielding uncertain, the lack of obvious candidates for replacement makes the whole situation precarious and suggests a chaotic transition of power when the necessity arises.

In such a resourceful and enormous organization as the CCP, there will always be a sufficient number of potential candidates ready for the task. Such leaders could have the career paths more like Jiang Zemin and Zhu Rongji, who appeared as national leaders out of necessity after the Tiananmen massacre – a fact reflected in their relatively advanced age (see the first chart above). But they were chosen by Deng Xiaoping himself, who continued as an informal supreme leader – and Deng didn’t forget to additionally pick up the very young Hu Jintao as the next in line, thereby confirming the necessity of grooming a successor.

This time, we can expect a much more contentious and chaotic power transition period, with an unknown number of still unrevealed candidates.