“ASEAN’s failure to move beyond its moribund consensus should be an overdue wake-up call for the administration of U.S. President Joe Biden,” Scot Marciel, a former U.S. ambassador to Myanmar, wrote this week, regarding the country’s ongoing conflict. Of the many moral and practical reasons why the international community must take a more hands-on approach to the Myanmar crisis, one often overlooked is to save ASEAN – the Association of Southeast Asian Nations – from itself.

It is not in the interest of Western democracies, Japan, South Korea, or China to have a weakened ASEAN, certainly not one pulled apart by bickering over how to respond to the Myanmar crisis, nor for the bloc to be humiliated by its ineffectiveness in handling a crisis with which it was never designed to cope. Southeast Asia is home to just under 9 percent of the world’s population and a little under that share of global trade. That’s only going to grow this century. It’s also located near geopolitical hotspots. The South China Sea disputes shade the maritime area. Taiwan is just over 1000 kilometers from the shores of the Philippines.

ASEAN is not a moral vehicle. It’s deeply cynical in its belief that it cannot interfere in the conduct of neighbors. ASEAN won’t do sanctions. There’s no love for democracy amongst half of the members. Thailand looks on, ruled by the same people who came to power in its own military coup. The governments of Cambodia, Laos, and Vietnam all came to power through the barrel of the gun, and have never since allowed it to gather dust. Singapore consistently briefs that it firmly stands behind ASEAN’s principle of non-intervention in other states’ affairs. Vietnam really doesn’t care. The Philippines doesn’t want any part in this, neither does Cambodia now that it’s no longer ASEAN chair. Malaysia appears to be losing interest. Indonesia (now ASEAN chair) says it intends a new bold policy, but there’s little evidence of it – and even if there was, it risks even more division and outright mutiny from the other members.

The junta’s failure since day one to stick to ASEAN’s Five-Point Consensus is deeply embarrassing for the bloc. ASEAN’s failure to admit this and punish the junta accordingly is far more serious. “We must understand that although we clearly disapprove of the coup, and we don’t recognize the current military junta, it does not give ASEAN a license to interfere in its domestic affairs,” Singapore’s foreign minister, Vivian Balakrishnan, said last weekend. Perhaps he would have been better off saying that ASEAN lacks any mechanism to meaningfully hold the junta to account. Even if the other nine members were united on a decision (which they’ll never be) ASEAN lacks teeth. Indeed, ASEAN lacks the will and the means to foster any positive change in Myanmar.

Its reputation has surely taken a beating since early 2021. Give ear to a Jakarta Post editorial published last November: “The world had pinned hopes on Myanmar’s closest neighbors in Southeast Asia to put pressure on the junta. But the continued defiance and the killing and jailing of its own people is creating a lot of frustration. Many are starting to question ASEAN’s effectiveness and credibility.” Or as Cambodia’s King Norodom Sihamoni said last year: “it can undermine the very foundations of our ASEAN Community, which we all have worked so hard to build.”

The Myanmar crisis has arguably been the biggest shakeup of the bloc since its expansion in the 1990s. Some politicians now talk openly about expelling a member. It’s debating the merits of strict non-intervention and what role values like liberty should play in regional affairs. Perhaps, seen positively, all this all a necessary response from a regional organization that had grown rather cumbersome and arrogant in recent years, too self-satisfied with the leaders of foreign powers who fly in to laud the notion of “ASEAN centrality” and the region’s successes. On the other hand, utopianism often breeds nihilism, and there’s nothing to suggest that the problems created by the Myanmar crisis won’t destabilize the bloc over the long term.

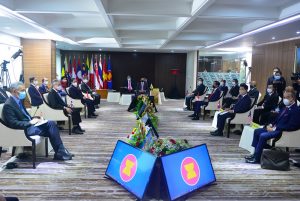

The danger is that ASEAN’s finer points are irrevocably blunted. It excels at forming trade agreements and pacts. It has tempered the underlying revanchism common amongst the populations of its members and which was a source of so much instability in the 20th century. And it’s a conduit to the outside world, not least by allowing the relatively powerless but prescient Southeast Asian states to play a grander role on the world stage than they would be able to do alone. It also brings foreign politicians together through its summits and dialogues. It’s not mere lip service when the leaders of major powers talk about ASEAN “centrality.” The Indo-Pacific is a far more peaceful place with ASEAN.

To put the matter bluntly: ASEAN needs an off-ramp. It needs to be provided with a way to extract itself from the crisis without too much shame, but one which, in the process, doesn’t undermine the Myanmar people’s struggle for liberty. This will necessarily mean a more proactive position from not just Western democracies but also from China and Japan. It may be overly sanguine, but the Myanmar crisis is one issue in global politics over which Washington and Beijing are not a million miles away from one another.

Perhaps, as many analysts suggest, the U.S. and other Western democracies need to increase their funding to the anti-junta resistance movement and offer far more recognition to the shadow National Unity Government (NUG). That should have been a given, despite what ASEAN thinks. Rather than playing peacemaker, ASEAN needs to become more of a conduit, the moderator that brings together other powers to discuss the issue. Or, instead, as with the South China Sea disputes, ASEAN needs to step away and allow individual Southeast Asian states to choose their own way on the Myanmar conflict, which might allow the likes of Indonesia and Malaysia to work more closely with the Western democracies (and allow the disinterested states, like Vietnam, to butt out of the crisis entirely).

The “how” is difficult. But the “why” is obvious. If the international community wants a healthy and confident ASEAN, one that can ensure Southeast Asia doesn’t become enmeshed in new Cold War divisions or member states don’t revert back to revanchism, it needs to offer ASEAN an out; a humiliation-free way of admitting defeat.