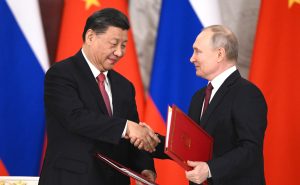

There is an almost hysterical need to find fissures in the Sino-Russian relationship. Yet, the most obvious thing to come out from Chinese President Xi Jinping’s visit to Moscow was the fact that both he and President Vladimir Putin want to highlight to the world how close they are. No one forced Xi to go to Moscow, and Putin chose to make this a high-profile state visit. Their warm words to each other overheard as they left dinner may have seemed staged, but at the same time were unnecessary unless the point was to emphasize partnership. The endless search for gaps misses this clear strategic alignment which should be taken and reacted to at face value.

The narrative of underlying disagreement and dislike between Beijing and Moscow is likely born from the same place that the Cold War Two concept emerges from. During the first Cold War, China and Russia were at odds beneath their common Communist spirit, and the U.S. demonstrated impressive diplomatic deft in focusing on this to pull them apart. The times have changed, however, and the key thing now holding China and Russia together is an antipathy toward the West.

It is abundantly clear that there are disagreements between Moscow and Beijing at every level. India, for example, is a power that has a strong relationship with Moscow, but a violent one with China. The Russian intelligence service continues to detain scientists they claim are selling their country out to China. Shortly before Xi’s visit a group of Chinese miners were murdered in the Central African Republic, with the Chinese leader pledging their murders would be avenged. A rumor rattling around the Chinese internet was that they had been executed by Russian Wagner forces. All of this serves to show competing geopolitical interests as well as bilateral paranoia at a public level and within their respective security apparatuses.

Similarly, the economic sphere is riven with contradictions. No big gas deal has yet been signed – likely evidence of China deciding to play hardball on negotiations now that they have the upper hand and more options at hand (as well as the fact that to rebuild the infrastructure within Russia to shift European-facing gas to Asia will take some time). Yet at the same time, Moscow is clearly looking to sell more to China and Beijing is buying. Within the private sector, some Chinese firms see the evacuation of Western brands from Russia as a great market opportunity, while at the same time large tech firms like Huawei or Alibaba are pulling people out or suspending investments. Opportunity and fear of secondary sanctions are often wrapped up together.

But in focusing on all of these contradictions, we are missing that this is often the nature of international relations. To paraphrase British Prime Minister Lord Palmerston: Countries have interests, not friendships. The transatlantic alliance may have NATO binding it together, but is equally riven with contradiction and disagreement – Turkey’s role in the negotiations around Finnish and Swedish membership has highlighted this. European and American companies usually compete on the international stage and within each other’s markets, while the authorities seek to protect their own national firms. And it is worth remembering that we are only two short decades since the U.S.-led invasion of Iraq – a war that tore at the fabric of the transatlantic alliance.

It is hard to understand why we cannot then see this echoed in the China-Russia relationship. Both have problems, disagreements, and contradictions with each other, and yet their leaders are happy to grandstand together on the world stage.

The overarching issues they wanted highlighted during this encounter was their proximity and the fact that they are both pushing forward the development of a non-Western led order (made up of institutions like BRICS, the Shanghai Cooperation Organization, and more). At an individual level, Beijing struck its pose as the peacemaker seeking to help resolve the Ukraine war (building on its success in the Middle East between Riyadh and Tehran), while Moscow got high level support on the global stage.

We have yet to see Beijing’s support go beyond this to actually arming Russia with the lethal hardware that they want to fight in Ukraine. And we have yet to see Moscow try to force Beijing to do something they do not want to do in advance of Russia’s interests.

The final point to make is that while it may be clear that Beijing increasingly has the whip hand in the relationship, this does not in itself necessarily mean anything. Growing Russian dependence on China does not hand all the chips to Beijing, but merely strengthens China’s hand in individual negotiations and potentially weakens Russian domestic capability in the longer run. This does not, however, lock Moscow into doing whatever Beijing wants. China has a few other “allies” in its immediate neighborhood where on paper it also has the “whip hand” – Pakistan, North Korea, and Myanmar – and in each case, Beijing struggles to get them to do what China might want. In fact, these countries have a tendency to do what they want rather than what China tells them to do, which sometimes actually appear to go against Beijing’s interests.

The West should take the Sino-Russian relationship at face value, focus less on how to pull the two apart and instead de-hyphenate them in their strategic thinking. They are not in lockstep across the board, but they are clearly in strategic alignment at a global level. Focusing on the relationship in this way will help identify where the differences mean one cares less than the other and therefore is a place where thinking of them as a union would be a distraction. It might also then offer some ideas as to where actually the differences in opinion matter on the ground, rather than seeking ones where little strategic advantage can be leveraged between Beijing and Moscow.