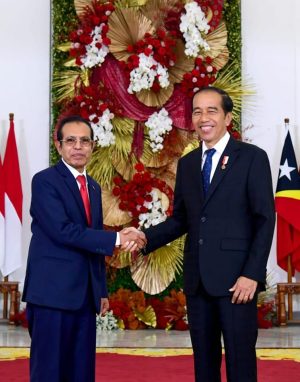

On February 13, Timor-Leste’s Prime Minister Taur Matan Ruak met his Indonesian counterpart President Joko “Jokowi” Widodo in the Indonesian satellite city of Bogor, home to one of the country’s many presidential palaces. It was from such palaces that Indonesian presidents once exerted political control over the former province of East Timor, which eventually split from Indonesia and officially became independent in 2002 after 24 years of occupation. Although East Timor was once described as the “pebble” in Indonesia’s shoe, the leaders of both countries now stood on even ground as “good neighbors,” despite their troubled past.

While both presidents were visibly pleased with the meeting, shaking hands and smiling for the press, the fact that a sitting Indonesian president happily met with a former Timorese resistance leader still going by his nom de guerre – Taur Matan Ruak means “two sharp eyes” – speaks volumes about how far the bilateral relationship has come over the past two decades.

The two countries signed off on several agreements to expand economic cooperation and improve technical cooperation in industry and higher education. They also reaffirmed their existing collaboration in the banking, energy, and telecommunications sectors. Importantly, Jokowi announced that Indonesia was in the process of drawing up a “full road map” for Timor-Leste’s admission as ASEAN’s 11th member state.

Timor-Leste, which was granted “in principle approval” to join ASEAN late last year, has been attempting to obtain full membership for over a decade – a decision that requires a unanimous vote from every member state. Last year, the country’s President José Ramos-Horta lamented that getting into ASEAN was akin to trying to get into heaven.

While many ASEAN member states continue to express trepidation about Timor-Leste’s accession, Indonesia has consistently been a staunch supporter of Dili’s membership.

With Indonesia at the helm of ASEAN this year, Timor-Leste undoubtedly has high hopes. Indeed, Dili probably views Jokowi’s chairmanship as a golden opportunity, even expecting Indonesia to maximize its position as chair to accelerate Timor-Leste’s admission. The last time Indonesia held the ASEAN chair was in 2011, the same year that Dili formally applied for membership to the regional bloc.

But why is Indonesia, once locked in a seemingly inescapable and bitter conflict with Timor-Leste, making Dili’s ASEAN bid a priority? To understand this, we need to first understand how Timor-Leste went from being a “pebble” in Indonesia’s shoe to a “good neighbor” in less than a decade.

Reconciliation and Rapprochement

The rapid rapprochement seen between Jakarta and Dili can be traced back to Indonesia’s democratization in the late 1990s. While international attention had begun returning to Indonesia’s brutal occupation of Timor-Leste after the 1991 Santa Cruz massacre, it was the downfall of Indonesia’s civil-military government under political strongman President Suharto in 1998 that paved the way for Timorese independence.

Facing both internal pressure to reform and external pressure caused by the 1997 Asian financial crisis, Jakarta’s hold over the province of East Timor became increasingly untenable. For Indonesia’s first post-Suharto civilian government under President B.J. Habibie, a referendum on the province’s separation from Indonesia was seen as a way of finalizing the issue. While Indonesia’s withdrawal from its former province was marked by violence, both Jakarta and Dili quickly moved to put history behind them.

This process of reconciliation was institutionalized through the Commission of Truth and Friendship, which was finalized in 2008. The commission didn’t seek to exact revenge or even obtain justice for the hundreds of thousands of victims of the occupation, but was a pragmatic mechanism for amnesties that allowed both countries to move forward with a blank slate. In other words, the Timorese were willing to trade justice for the new nation’s peace and prosperity.

From Jakarta’s perspective, there was a need to move past the legacy of “losing” East Timor – a cataclysmic event given Indonesia’s dogmatic view of its territorial integrity. Importantly, however, Indonesia’s relinquishment of Timor-Leste was always going to be a necessary step in solidifying Indonesia’s newly found democratic identity and securing the financial assistance it needed to fix the country’s dismal fiscal state. Certainly, any ongoing aggravation against the newly independent country would have only served to isolate Jakarta and evoke haunting memories of Konfrontasi.

Dili’s willingness to look past Indonesia’s 24-year occupation is perhaps the most surprising part of its relations with Jakarta today. Whether this forgiveness is nominal or genuine among Timor-Leste’s political elite is difficult to know, but the decision to move forward was one rooted in a realistic appraisal of the enormous challenge of nation-building that faced Dili after gaining independence. Cordial relations with Indonesia, a country whose borders still echo memories of invasion, were seen as necessary for Timor-Leste’s security and economic survival.

Since 2002, the bilateral relationship has continued to grow. Despite an ongoing land border dispute, Indonesian leaders have frequently referred to Timor-Leste as a “good neighbor,” with Jokowi even calling both countries “close brothers.” Indonesia remains one of Timor-Leste’s most important trading partners and both countries have continually expanded military ties, mostly in the form of training opportunities for Timorese officers in Indonesia.

But in a relationship where Dili clearly needs Jakarta more than Jakarta needs Dili, why has Indonesia been at pains to see Timor-Leste join ASEAN?

A Win-Win for Jakarta and Dili

For Indonesia, and indeed Jokowi himself, Timor-Leste’s admission into ASEAN is a win-win prospect that would benefit Indonesia’s security, boost its regional influence, and augment its political clout.

Firstly, Jakarta’s engagement with Dili has always been about ensuring stability on its borders. After all, it was Jakarta’s fears of a Southeast Asian “Cuba” on its doorstep that drove Suharto to invade the former Portuguese colony in 1975.

Indonesia and Timor-Leste share a land border on the island of Timor, with there being a Timorese exclave known as Oecusse inside Indonesia’s half of the island. Supporting Timor-Leste’s development and maintaining cordial relations benefits Jakarta as much as it does Dili. An underdeveloped Timor-Leste, or worse, a failed state, would create a “weak underbelly” for Indonesia’s overall security. For its part, Timor-Leste has experienced its fair share of instability since 2002. A political crisis in 2006 saw foreign troops intervene on behalf of the Timorese government after dozens were killed and 15 percent of the population was displaced by political violence.

Bringing Timor-Leste into the ASEAN fold is a way of boosting the country’s underdeveloped economy, which to this day remains highly dependent on the export of hydrocarbons. Indeed, as one of the region’s youngest and most underdeveloped countries, Timor-Leste stands to benefit immensely from greater access to the ASEAN market and the bloc’s vision for an ASEAN Economic Community.

Secondly, Timor-Leste’s admission into the bloc would help firm up Jakarta’s influence over Dili by further integrating the country into Southeast Asian regionalism.

Indonesia has long been touted as the “first among equals” within ASEAN, meaning Timor-Leste’s accession would provide Jakarta with another mechanism through which it could influence Dili. On the other hand, Timor-Leste’s integration into Southeast Asian regionalism is a way for Jakarta to ensure that the influence of other foreign powers is diluted.

First among these fears is China’s outsized influence in the small island nation – one led by a seemingly never-ending list of white elephant projects. Portugal and Australia, one a former colonizer and the other a leader of the U.N.-mandated intervention force that went into the country after Indonesia’s chaotic withdrawal, also maintain strong levels of influence in Timor-Leste today. Pulling Dili further into its orbit through ASEAN-centric mechanisms at the expense of China and Timor-Leste’s historic links to the Lusophone world is certainly part of Jakarta’s calculus.

Finally, while some have framed Indonesia’s support for Timor-Leste’s ASEAN membership as a way of paying a “lifelong debt” to the Timorese, gaining political clout and shoring up a political legacy is probably just as important. While Jokowi is unlikely to get Timor-Leste’s ASEAN bid through the necessary bureaucratic hurdles under his chairmanship, he will probably still make it a priority and see the country further integrated into ASEAN-centric mechanisms as an “observer.”

Jokowi is unequivocally a domestic president, having focused on infrastructure development and carving out his own legacy by moving the country’s capital to East Kalimantan. Unlike his predecessor Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono – a true foreign policy president known for his summit diplomacy – Jokowi’s engagement on the international stage has tended to have a clear domestic agenda behind it.

But as he nears the end of his two-term presidency in 2024, Jokowi may look to secure his own legacy on the regional stage as ASEAN’s chair. Hinting at their troubled past during a meeting with Jokowi last July, Timorese President Ramos-Horta said it would be “highly symbolic” for Timor-Leste to be admitted into ASEAN under Indonesia’s chairmanship. While such a move would represent a foreign policy, and arguably a domestic coup for Jokowi given both countries’ interlocked past, ASEAN’s consensus-driven politics will continue to be the deciding factor in Timor-Leste’s ASEAN bid.