Last month’s arbitrary arrest and disappearance of Afghanistan’s torchbearer for education dims any hope that millions of young Afghan girls have to resume their studies.

Matiullah Wesa, 30, tirelessly traveled from village to village, at times with mobile libraries, distributing books to children, many of whom had never touched one before.

The fearless education activist would address crowds of destitute and helpless villagers, including children, in the south and in rural eastern villages ravaged by constant wars and exhausted by poverty. Many of his listeners would stand barefoot on dusty terrain, dressed in tattered garments under the scorching sun. His message was straightforward: Both boys and girls belong in schools. Wesa helped impoverished communities rebuild schools, build libraries, and provide books and other educational materials.

For the past 14 years, he deliberately stayed out of politics and only worked with Afghanistan’s most vulnerable communities, most of whom remained out of sight of Afghanistan’s pro-U.S. governments, which received billions of dollars in aid from international partners, mainly the United States, to rebuild infrastructure, with education being a key component.

The majority of Wesa’s efforts were channeled through PenPath, a nonprofit he founded in 2009 at the age of just 17. PenPath has the primary goal of “advocating for education in Afghanistan, combating endemic corruption in the education sector, and establishing libraries,” among other commendable endeavors.

In a traditional and patriarchal society like Afghanistan, where gender inequality has persisted for generations, Wesa took it upon himself to raise awareness about the importance of educating girls. He mostly spoke to men in far-flung villages about the importance of allowing their daughters to attend school.

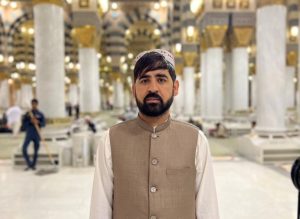

Dressed in traditional Afghan apparel, adorned with an intricately embroidered Kandahari cap and handmade Kandahari shirts, the lone education activist seamlessly blended in with the communities of rural Afghanistan.

Throughout southern Afghanistan, and Kandahar in particular, teenage girls and women are well renowned for the colorful male caps that they make, which are embellished with colorful beads, gold lace, and small circular mirrors. Women in this region also sew men’s silk-twill shirts, a process that can take months. But the women of southern Afghanistan take great pride in their regionally unique craft. Wesa regularly, and passionately, showcased the talents of local women by donning these shirts and caps.

In his own right, he was a villager and native of Kandahar. His appearance was different from the stereotyped, primarily Western, education activist who wore shirts and pants, were clean-shaven, and spoke using complex words, erecting a barrier that made it challenging for the peasants to understand and connect with the message.

Wesa was better understood by the people of rural Afghanistan because he was one of them. He explained, in terms that resonated with his audience, how educated women enable their communities to thrive. He asserted, for example, that even if a girl is impoverished, she will be able to save lives if she completes high school and becomes a nurse.

His concrete reasoning struck home with many in a community where a woman dies during childbirth every two hours. An Afghan man, regardless of his social standing, must spend a fortune to find a wife.

However, despite his selfless efforts, danger eventually caught up with him.

Wesa’s Arrest

On March 27, Matiullah Wesa was arbitrarily detained by the Taliban’s General Directorate of Intelligence (GDI) while returning from evening prayer at a mosque. The GDI also raided his house the next day after his arrest and confiscated his mobile phone and laptop.

On March 29, the Taliban spokesperson confirmed his detainment, citing “illegal activities” as the grounds for his capture. His family has been denied access to Wesa, and there is no means of contesting the legitimacy of the allegation against him.

Since his arrest, the Taliban have only offered vague statements, claiming that his activities raised “suspicion” and that he is under investigation. Prior to his arrest, Wesa was getting ready to speak at a meeting about girls’ education, the predicament of Afghan women and girls, and the best ways for the outside world to assist. His seat was left vacant after his detention.

What does the general public think about Wesa’s arrest? Many Afghans believe that the Taliban are using restrictions on women and girls in general, as well as the arbitrary arrests of prominent activists like Wesa, as bargaining chips to pressure the rest of the world into meeting their demands, including gaining international recognition. Many believe the Taliban’s exploitation of Wesa’s image and his subsequent arrest are meant for their political gain, especially considering that he was not even involved in politics.

Others claim that Pakistan has long supported and trained the Taliban as its proxies in an effort to cripple Afghanistan’s educational system and the basis for any prospects for recovery – hence the ban on education for millions of female students.

After his arrest, Taliban supporters went so far as to circulate pictures from Wesa’s phone online, falsely accusing him of engaging in immoral behavior. These photos, which at least some Taliban followers posted on social media, show him sitting with young Afghans, including women in Islamic hijabs; some of them are even wearing face masks. They appeared to be in a group discussion; a sane viewer would see nothing in those photos that suggests anything immoral.

In a photograph that circulated on Twitter and was allegedly taken from his phone, Wesa is pictured with a group of young men and women eating pomegranates, a fruit native to Kandahar.

If Taliban sympathizers and supporters hoped to use these images to smear his reputation, the move was both pointless and ridiculous.

The people of Kandahar are most proud of producing pomegranates and giving the country its founding father, Ahmad Shah Abdali. When pomegranates are in season, Kandahar residents customarily serve them to their most distinguished guests; many believe that the sweet and sour taste of their pomegranates cannot be found anywhere else in the world.

Many Afghans thus retweeted the photo, saying, “Pomegranates are not a forbidden fruit in Islam,” mocking the Taliban for failing to find any evidence that Wesa had engaged in any unethical behavior.

Wesa was a man of God. On February 28 of this year, he tweeted that he had completed Umrah, a pilgrimage to Mecca that is a shorter version of the annual Hajj gathering that Muslims are expected to perform at least once in their lives. “I am so grateful to Almighty Allah! I am very lucky to be able to complete Umra. I prayed for all my friends, family, Afghans, and my beloved country,” he wrote.

A devout Muslim, he worked relentlessly to promote girls’ education, which often meant engaging with foreign delegates, including women, and visiting European capitals. On his Twitter account, Wesa shared photos from work trips he took. In those photos, Wesa’s embroidered cap often makes an appearance atop his dark hair.

He always spoke calmly, yet his mission to foster a culture of literacy in Afghanistan challenged the Taliban’s ideology.

A Dark Future

Since taking control of Afghanistan in August 2021, the Taliban have gradually extended the ban on girls’ education. The sudden departure of the former president of Afghanistan signaled a grim conclusion to the people’s long fight for fundamental human rights, which included the rights of women to pursue education, employment, and engage in communal activities.

As soon as the Taliban ascended to power, they announced the closure of girls’ schools and universities, and soon barred women from working with both local and global organizations.

Though sporadic protests were witnessed in Kabul, Jalalabad, Khost, and other cities, the Taliban’s stance remained adamant. They insisted that the ban was temporary and conditional, subject to meeting a certain criterion appropriate for the safe resumption of girls’ education.

However, the requirements for a return to normal life for girls and women remain shrouded in obscurity, and the Taliban have never fully explained what those conditions entail. The prospects of reopening schools and universities to female students continue to be remote as the second anniversary of the imposition of the ban draws near.

The Taliban have made Afghanistan the only country in the world that forbids girls and women from attending school. It threatens to undo the huge educational gains made over the last two decades, despite all the challenges. According to a United Nations estimate for 2023, the ban will deprive 2.5 million girls over the age of 12 of an education.

Against this backdrop, Wesa’s arrest infuriated many regular Afghans, especially those on social media, who strongly condemned the international community for not doing more than expressing sympathy.

A trusted friend of Wesa, who spoke on the condition of anonymity, revealed that his unwavering commitment to challenging the Taliban’s ideology on women’s education and rights may have led to his arrest: “In Afghanistan, he was doing what the people of Afghanistan expected the free world to do.”

Wesa tirelessly championed what trapped Afghans yearned for: a world where education is a right for every girl. With time not on their side, he took on the task single-handedly, knowing that the change they needed could not wait any longer.

He aimed to show the world two things. The first was that the denial of Afghan girls’ right to education is a human rights abuse, and that the world needs to act urgently to change the grim reality for the millions languishing under Taliban rule.

Second, as an Afghan man advocating for girls’ education, he shattered the wrongful perception that Afghans are against education for women, a stance that the Taliban claim is rooted in the country’s tradition. Wesa aimed to show the free world the reality from the perspective of ordinary Afghans and gain the courage to act.

The Taliban authorities’ stance on women’s education is rooted in their interpretation of Islam. Many of them believe – and have not shied away from publicly stating – that women’s sole duty is to care for the home and please their husbands. This doesn’t require women to have an education, they say.

Others referred to schools as prostitution dens, claiming that women picked up Western ideas of immorality in schools. This is unprecedented in the Muslim world. Afghanistan under the Taliban is the only country in the world where girls and women are barred from public life simply for being female, making the Taliban the world’s most visible gender apartheid regime.

Wesa was fearless in opposing the Taliban’s misogyny. He made his stance clear on Twitter, and said he would fight “until the end to ensure that every girl in Afghanistan can attend school.”

Millions of Afghan women and girls who are prohibited from participating in public life are reminded of the Taliban’s tightening hold on their freedoms by Wesa’s detention. Many view his arrest as evidence that it may be naive to expect the free world to do action beyond issuing press releases and condemnations to ensure Afghan girls have access to school, and women can go back to work.

One of Wesa’s final tweets strikes a note of hope: “Every day, morning, evening we receive messages from desperate people eagerly asking when girls schools will open?! I always give them some sort of hope that yes schools will open and for them to be patient. This is our right and till when [sic] we should wait.”

Just days later, Wesa’s brother spoke to the BBC from an undisclosed location, expressing serious concern for Wesa’s well- being. He stated that the family has no idea what happened to Wesa following his arrest.

“Wesa has vanished,” he said. The already faint hope for Afghan girls’ education has all but vanished as well.