Russia and China share one of the world’s longest borders, but the two sides conduct oil trade via maritime shipments, not pipelines. Defense analysts should therefore not assume that the U.S. and Allied Navies cannot interdict Russia-to-China oil shipments, although there are a number of political and military realities that make such a blockade extremely unwise outside of wartime or near-wartime conditions.

Russian Crude Oil Exports to China are Largely Seaborne, and Not as Important as Many Think

Russia’s overland crude oil pipeline export capacity to China is significant but limited. The East Siberia Pacific Ocean pipeline (ESPO) plays an important role in Russia-to-China crude oil flows, yet ESPO’s mainland China spur can only deliver about 35 million metric tons per annum, or about 0.7 million barrels per day (MMBPD), to refineries in north China. Indeed, most ESPO oil heads to Russia’s Kozmino Pacific Ocean export terminal, where it is then shipped to various destinations, especially the PRC.

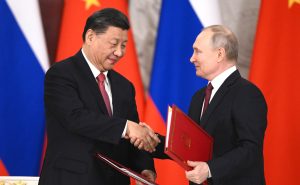

China also has overland – and indirect – pipeline ties to Russia via the Atasu-Alashankou pipeline, which transits Kazakhstan. This pipeline connection only has a capacity of 20 million tons per annum, or about 0.4 MMBPD. During the February 2022 Xi-Putin summit in Beijing ahead of the Ukraine invasion, Russia’s Rosneft oil company inked a deal with state-owned China National Petroleum Company to supply 0.2 MMBPD to China along this pipeline. Kazakhstan has historically shipped only about 20,000 bpd via Atasu-Alashankou, implying that the route could see more future flows if Kazakhstan and/or Russia can ensure adequate upstream production volumes.

At current levels, however, the two overland pipelines connecting China to Russian crude have a total maximum throughput capacity of only 1.1 MMBPD. China can import much more from Russia via tankers and is already doing so.

Russia-to-China crude flows have traditionally stood at about 1.6 MMBPD, with volumes split between overland and maritime routes, according to China energy expert Erica Downs. The overland/maritime balance shifted after Moscow invaded Ukraine, however, as Russian seaborne oil exports, shunned by Western markets, found their way to China and India via tankers. While data on Chinese maritime imports of Russian crude is somewhat opaque in the wake of sanctions, industry-leading estimates show weekly flows often well over 1.1 MMBPD. Indeed, the latest figures suggest China imported nearly 43 million barrels from Russia in March, for an all-time monthly record of nearly 1.4 MMBPD. Moreover, market participants have told this author that China’s total (pipeline and maritime) imports of Russian could theoretically reach as high as 3-3.5 MMBPD, although 2.5 MMBPD may be a more plausible maximum this year. In any event, tankers – not pipelines – are being used to conduct the majority of Chinese-Russian crude oil trade volumes.

Russian crude imports, while very important, are not as critical to Chinese energy security as some believe. China imported approximately 10.1 MMBPD of crude oil in 2022, via both pipelines and seaborne tankers. Russian total crude oil exports – including overland and seaborne routes – only accounted for about 1-in-6 barrels of Chinese imports in 2022. Russian oil exports to China are important, but Beijing sources the overwhelming majority of its crude oil imports from elsewhere.

A Blockade of Russia-to-China Crude Oil Shipments is a Foolish Idea Outside of Extreme Circumstances

While there are no serious calls for a blockade of Russian crude shipments to China, the risk of a PRC blockade or quarantine of Taiwan is rising, leading Western analysts to consider countervailing responses. Any blockade of Russian crude exports to China would carry extreme risks, raise the potential of escalation, and bring little-to-no benefit. A peacetime blockade of Russian crude exports to China should not be considered. In a wartime or near-wartime scenario, however, such as a PRC blockade or quarantine of Taiwan, the West may be able to disrupt Russian crude shipments to China, if necessary.

Blockading Russian crude exports would pose severe risks under any circumstance. Politically, any blockade would arouse the wrath of both Moscow and Beijing, poisoning whatever is left of the West’s relationship with the authoritarian bloc. A maritime cordon would also be difficult to enforce militarily, due to the presence and anti-access/area denial (A2AD) capabilities of the PRC’s People’s Liberation Army Navy, or PLAN, and Russia’s Pacific Fleet. Declaring a blockade, then failing to enforce one, would severely damage Western credibility and would likely be worse than doing nothing. Moreover, a blockade – with U.S., Russian, and Chinese warships near one another – would increase horizontal and vertical escalation risks. Due to these immense risks, there is no reason to even consider a blockade, outside of extreme circumstances.

In the event of a blockade or quarantine of Taiwan, or another near-wartime or wartime scenarios, however, Western forces could consider severely disrupting the Russia-China oil trade via cyber methods, covert action, stand-off capabilities, or some combination of the above. All these measures would bring extreme risks, however.

With Russia continuing to demonstrate poor signals intelligence (SIGINT) performance in the war in Ukraine, the West could likely easily find seams in Russian cyber defenses and disrupt Moscow’s upstream oil production, midstream transportation, or both. This option could lead to retaliatory Russian and/or Chinese cyberattacks and would likely have only a limited and temporary impact on Russia-to-China crude oil shipments, however. While a cyberattack poses the least risky blockade option, it nevertheless poses serious dangers and few benefits.

Alternatively, but much more riskily, the West could undertake covert action and disrupt shipments from the Kozmino oil export terminal and other Russian oil assets. A covert kinetic action on Russian territory would probably be detected, could easily fail to achieve its operational objectives, would only temporarily affect oil flows to China, and might lead to Russia attacking countervailing US critical infrastructure.

Finally, the U.S. and its allies could, in the event of a Chinese blockade on Taiwan, announce they would target unladen tankers returning to Russia after dropping off crude shipments in China. Targeting unladen tankers, in the event of a blockade of Taiwan, would reduce (but not eliminate) the environmental impact of disrupting the oil trade between Moscow and Beijing and minimize public opinion damage. Moreover, leveraging Western A2/AD capabilities, especially long-distance, shore-based anti-ship missiles, would not expose Western forces to undue risk. A kinetic strike on a Russian tanker, even an unladen one, would nevertheless pose enormous environmental and reputational risks. It could also lead to horizontal or vertical escalation and should not be considered outside of extreme circumstances.

Blockading Russian Crude Exports to China is Feasible, but Foolish

Russian oil shipments to China have become increasingly maritime in character and are likely to remain so – barring an expansion of Russian overland pipeline capacity to China. The U.S. and its allies and partners therefore could, if necessary, disrupt or even eliminate Russian maritime crude oil exports to China. Doing so would be extraordinarily risky, unnecessary, and useless, however. A blockade on Russian crude oil exports bound for China would pose severe political and military risks and disrupt only a small fraction of China’s import shipments.

The West, broadly defined, needs to consider the risks of a PRC blockade or siege of Taiwan, signal its strong preference for the status quo, and identify suitable countervailing pressure points. Blocking Russian oil exports from reaching China is not one of them.