The escalating power struggle between China and the United States, along with their respective allies, has amplified the significance of retaining a military presence in proximity to strategic choke points in the Indian Ocean. This has imposed immense pressure on smaller nations positioned along those chokepoints, given that any action they undertake is subjected to close scrutiny by those vying for supremacy in the new global power dynamics.

Unfortunately, smaller nations often lack a comprehensive understanding of the larger security context, which leaves them ill-equipped to devise an effective communication strategy to allay the concerns of other stakeholders. As a result, these nations struggle to effectively navigate the complex web of regional and global power dynamics that are at play, which further exacerbates their precarious position in the power struggle between the major powers.

Radar Stations in Myanmar and Sri Lanka

The reaction of the Indian security establishment and its media to reports of alleged Chinese-funded/operated “radar stations” in Myanmar and Sri Lanka are good examples of this.

In January 2023, Maxar Technologies, a company that works closely with the U.S. government, released satellite images that showed renewed construction activities on Myanmar’s Great Coco Island. The photos show two new hangers, a new accommodation block, and cleared land which is speculated will be used for more new constructions.

In a report for Chatham House Damien Symon and John Pollock pointed out that India has always worried that China could use Myanmar to spy on its navy in the context of Great Coco. “Conspiracy theories dominate the recent history of the Coco Island chain. Despite efforts to debunk them, they underpin almost all the conjecture around Great Coco, with any activity by Myanmar to reinforce its military presence seen as having a Chinese hand behind it,” they claim.

Quoting an “anonymous source in the security establishment,” the Indian daily, The Hindu, said that the constructions are being carried out “entirely by the Chinese” and that these facilities could be used by the Chinese military “when required.”

Meanwhile, Indian media quoting “intelligence sources” speculated that China is planning to establish a radar station in Sri Lanka’s southern region. According to the Economic Times, the proposed radar station could track the activities of the Indian Navy, and the “strategic assets in the Southern part of the country, including Kudankulam and Kalpakkam nuclear power plants. The proposed radar will also be able to track US military activities in Diego Garcia.”

“Chinese bases” in Myanmar and Sri Lanka

In recent decades, the Chinese presence in Sri Lanka and Myanmar has been the subject of speculation, controversy, and geopolitical intrigue. India believes that the two nations are an intrinsic part of a Chinese strategy to box it in and Indian media has been churning out hundreds of speculative articles relating to China being behind various developments in these nations and that these pose a grave national security threat to India.

With relations between Myanmar’s generals and China warming in the 1980s, a stream of reports emerged speculating that Myanmar would have become a “satellite” or “client state” of an expansionist China. There were two main reasons for this perception — one was the large and growing number of arms sales from China to the Myanmar junta and the other was frequent references in the media, academic literature and books to the presence of Chinese military bases in Myanmar.

In August 1992, when a Myanmar Foreign Ministry delegation went to New Delhi for talks, Indian officials made the first public reference to Chinese military bases in Myanmar. Indian Foreign Minister J. N. Dixit told the Myanmar delegation that India “made no secret about its . . . knowledge of Burma’s justification in providing construction materials to China for building a naval reconnaissance facility in a sensitive area near the Indian border [sic].”

High-ranking officials in New Delhi, who spoke on condition of anonymity continued to fuel these speculations. As a result, the idea of a significant Chinese military presence on Myanmar’s islands is now treated as fact.

Andrew Selth, adjunct professor at the Griffith Asia Institute at Brisbane’s Griffith University, says that upon careful analysis of the available evidence, it appears that there is no proof of the existence of Chinese military bases on Burmese territory. He adds that India’s Chief of Naval Staff Admiral Arun Prakash, in 2005, publicly stated that India had “firm information that there is no listening post, radar or surveillance station belonging to the Chinese on Coco Islands.”

However, this has done little to dissuade reporting on the Chinese presence in Myanmar.

Similarly, there is much speculation over a Chinese military presence in Sri Lanka. Such speculation is often centered around the Port of Hambantota, which Sri Lanka leased to China Merchants Port Holdings Company Limited for 99 years for $1.12 billion in 2017.

On November 2, 2021, the U.S. Department of Defense issued a report titled “Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China,” which stated that China has likely contemplated establishing a military base in Sri Lanka.

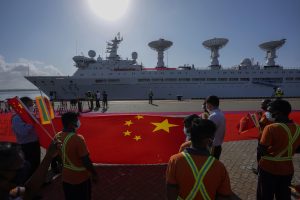

Last year, the controversy surrounding the Chinese research vessel Yuan Wang 5 showed how much India and the West are concerned with alleged signals intelligence gathering by China in the Indian Ocean.

The more recent allegations that China is planning to establish a radar station in Southern Sri Lanka relate to a project under which China plans to provide Sri Lanka’s Ruhuna University with Generation-1 capacity optical satellite imagery from a Chinese constellation. Sri Lanka’s The Morning newspaper reported that these “can be used for a range of studies including in agriculture, irrigation, cloud pattern analysis, weather prediction, coast conservation and town planning” The report went on to say that “if established, it may be the first such facility that allows local academics to have access to such technology.”

Lessons for Sri Lanka and Myanmar

Many analysts rely heavily on news reports to gather information about events in Myanmar and Sri Lanka. However, these reports – with notable exceptions – have proven to be an unreliable source of information, rooted in speculation, rumor and even fabrication.

Unfortunately, such claims have been accepted without sufficient scrutiny and are repeated in other articles and monographs. Once published, these claims are cited by other authors, lending them an unwarranted level of credibility.

Despite the significance of their developing ties and the interest of regional and international stakeholders, neither Myanmar nor Sri Lanka or even China have made a robust effort to clarify matters. While the usual mundane press releases are issued, few specifics are available regarding terms of their economic agreements, or the exact nature of their defense links. Similarly, little is known about the strategic thinking of the Myanmar junta, beyond its abiding sense of insecurity and apparent fear of foreign military intervention to restore democratic rule.

This lack of transparency has led to the emergence of various and often conflicting theories over the past 15 years, seeking to explain China’s relationship with Myanmar and Sri Lanka and its potential implications for regional security.

In his recent book “Teardrop Diplomacy,” noted Sri Lankan geopolitical analyst Asanga Abeyagoonasekera, who is senior fellow at The Millennium Project, points out that several of India’s neighbors have failed to effectively and transparently communicate their dealings with China to the wide world.

Abeyagoonasekera added that Sri Lanka is at a geopolitically vital location and almost all the major powers are interested in a foothold here. Although, Sri Lankans don’t want to be involved in international intrigues, successive governments have failed to convince China, India and the U.S. that its foreign policy is nonaligned, he said.

“Sri Lankan governments would agree to carry out various projects with foreign powers, thinking of financial gains. They do not understand the broader security context. Sri Lanka needs to mobilize all its resources to convince the major players that it doesn’t plan on picking sides,” he told The Diplomat.