Since entering office in October 2021, Japanese Prime Minister Kishida Fumio has embraced many of the underlying principles of former Prime Minister Abe Shinzo’s proactive diplomacy – no surprise, since Kishida served as Abe’s foreign minister for five years. But times have changed. Following the Russian invasion of Ukraine, and the growing tensions between China and the United States, the pressure on middle powers to choose sides has become more acute. The Russian invasion has ramifications for stability and security in East Asia, raising fears that China will invade Taiwan. Furthermore, North Korea has increased its missile launches, including test flights over the territory of Japan. In this new geostrategic environment, Japan had to create a new strategy combining power projection and enhanced pragmatic diplomacy.

In the security sphere, Kishida revised the foundational documents of Japan’s national security: the National Security Strategy (NSS), National Defense Strategy, and Defense Buildup Program. The updated NSS described China as “an unprecedented and the greatest strategic challenge,” and Russia as a strong national security concern. The NSS and the related defense documents focus on Japan’s need to develop its counterattack, cyber, and missile defense capabilities. To support this, the Japanese government approved the largest defense budget in history, set at $51 billion, reflecting a 26.3 percent rise in defense spending. The Japanese strategy shift came hand in hand with a stronger emphasis on human rights, focusing on China’s human rights abuses.

Equipped with a new strategy, Kishida will host the G-7 summit in Hiroshima this May. He set out early this year to brief his G-7 partners on Japan’s program for its year as G-7 president. In January he visited France, Italy, the United Kingdom, Canada, and the United States. In March, Kishida hosted the final G-7 leader, Germany’s Chancellor Olaf Scholz, in Japan.

But it’s important to note that Kishida has not limited his diplomatic efforts to the G-7 members alone. In March he hosted South Korean President Yoon Suk-yeol, the first such visit since 2011. In May he paid a return visit to Seoul, addressing the suffering and pain during Japanese occupation of Korea, in a signal of rapprochement between the two U.S. allies. Kishida has invited Yoon to attend the G-7 summit as a guest, meaning Yoon will travel to Japan yet again next week.

In March, Kishida traveled to India, where he met with his close Indo-Pacific partner, India’s Prime Minister Narendra Modi, and announced his commitment to a free and open Indo-Pacific, including helping emerging markets in the region. Kishida also invited Modi to attend the G-7 summit as a guest.

Right after his India trip, Kishida also made a surprising visit to Ukraine, pledging additional aid, sending a clear message of support and condemnation of Russia’s violence. At the same time, Chinese President Xi Jinping was in Russia to show solidarity with President Vladimir Putin, in what was seen as a demonstration of a clear divide between the democratic camp and the authoritarian camp.

But while a divide between democracy and autocracy might play well in the United States and Europe, it resonates less in the Global South more generally. Although the divide between the two camps is deepening, there are many countries who do not want to choose sides. These countries have been severely impacted by the superpower competition and the Russian invasion that led to hikes in prices, hampering the progress of these emerging markets.

Despite many of these countries not being fully democratic, the liberal camp should not discard them. This is not a zero sum game – there are many opportunities for cooperation with non-aligned countries and Japan has an important role in leading this effort. Especially in the current geostrategic atmosphere, it is necessary for the liberal camp to engage with the Global South and offer it a viable alternative to China.

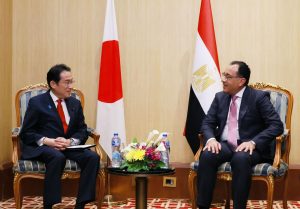

As a demonstration of Japan’s commitment to the developing world, Kishida spent a week in early May – crucial time in the lead-up to the G-7 summit – visiting four African countries: Egypt, Mozambique, Ghana, and Kenya. His intension was clear: to convince leaders in the Global South that the G-7 summit is relevant and even beneficial for them. In that regard, it’s important to note that Japan has invited the current chair of the African Union, Comoros, to attend the upcoming G-7 summit.

Kishida said in Mozambique that “the G-7 will take steps at the next summit to demonstrate a greater involvement in the Global South.” He added, “Japan must maintain its commitment to the rule of law and serve as a bridge between the G-7 and the Global South.”

In an attempt to offer a sustainable alternative to China, Kishida had discussions with the four African countries on ways to advance economic cooperation. Japan has a lot to offer African countries, and the Global South more broadly, especially in tech, innovation, and financing for mega projects. Although such cooperation is welcomed by African countries, it does not guarantee their support of the broader Japanese goal of gaining support of the FOIP and solidarity toward Ukraine.

Japan’s engagement with the Global South continued with the visit by the prime minister of Bangladesh, Sheikh Hasina, to Tokyo. Japan attaches great importance to Bangladesh, as its rapidly growing economy generates many opportunities for enhancing investments and joint projects in the energy sector, cybersecurity, and more. Nonetheless, Tokyo’s interest in Bangladesh is not limited to economic cooperation alone.

During Hasina’s visit, Japan – a long time contributor to the Bangladeshi economy – finalized its funding of the Matarbari deep sea port in Bangladesh, in a move that emphasizes the value of Bangladesh to Japan’s FOIP strategy and as a connecting hub between South Asia, East Asia, and the Middle East. The deal comes after the failure of India and China to develop the Mongla port, proving that Japan can offer an alternative for the Global South.

Japan’s new proactive strategy is instrumental in increasing cooperation and pragmatic engagement with the Global South countries. Ahead of the G-7, Japan has an opportunity to manifest its multifaceted policy more effectively, not only with an elite group of like-minded countries but with the very much important Global South as well.