Located on the west side of Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park, a 4.5 meter stone tower stands on a large turtle-shaped base. The turtle faces the direction of the Korean Peninsula; as Korean legend goes, the spirits of the dead ascend to heaven on the back of a turtle. At the top of the tower, there is a crown engraved with two dragons.

This is the memorial dedicated to South Korean victims of the 1945 atomic bombing of Hiroshima.

Japanese Prime Minister Kishida Fumio and South Korean President Yoon Suk-yeol will visit this monument on the sidelines of the Group of Seven summit in the city, which will take place from May 19 to 21.

With the two leaders expected to lay a bouquet of flowers and bow deeply before the memorial stela, their visit will be surely a very passionate and emotional event, staging a dramatic political show that marks a watershed in the historic reconciliation between the two nations. No South Korean president has ever visited the memorial in Hiroshima before, as those Korean A-bomb victims have been largely a “forgotten people” in their mother country.

As for Japan, Kishida will become just the second sitting prime minister to visit the stone tower since its completion in 1970. Obuchi Keizo paid his respects with a visit on August 6, 1999, making him the first – and, until next week, the only – Japanese prime minister to do so.

It is said that there were about 3 million Koreans in Japan at the end of World War II. The Korean Atomic Bomb Victims Association estimates that 50,000 Koreans were exposed to the atomic bombing of Hiroshima, of whom 30,000 died. They were both residents of the city and forced laborers brought from the Korean Peninsula during Japan’s colonial rule from 1910 to 1945.

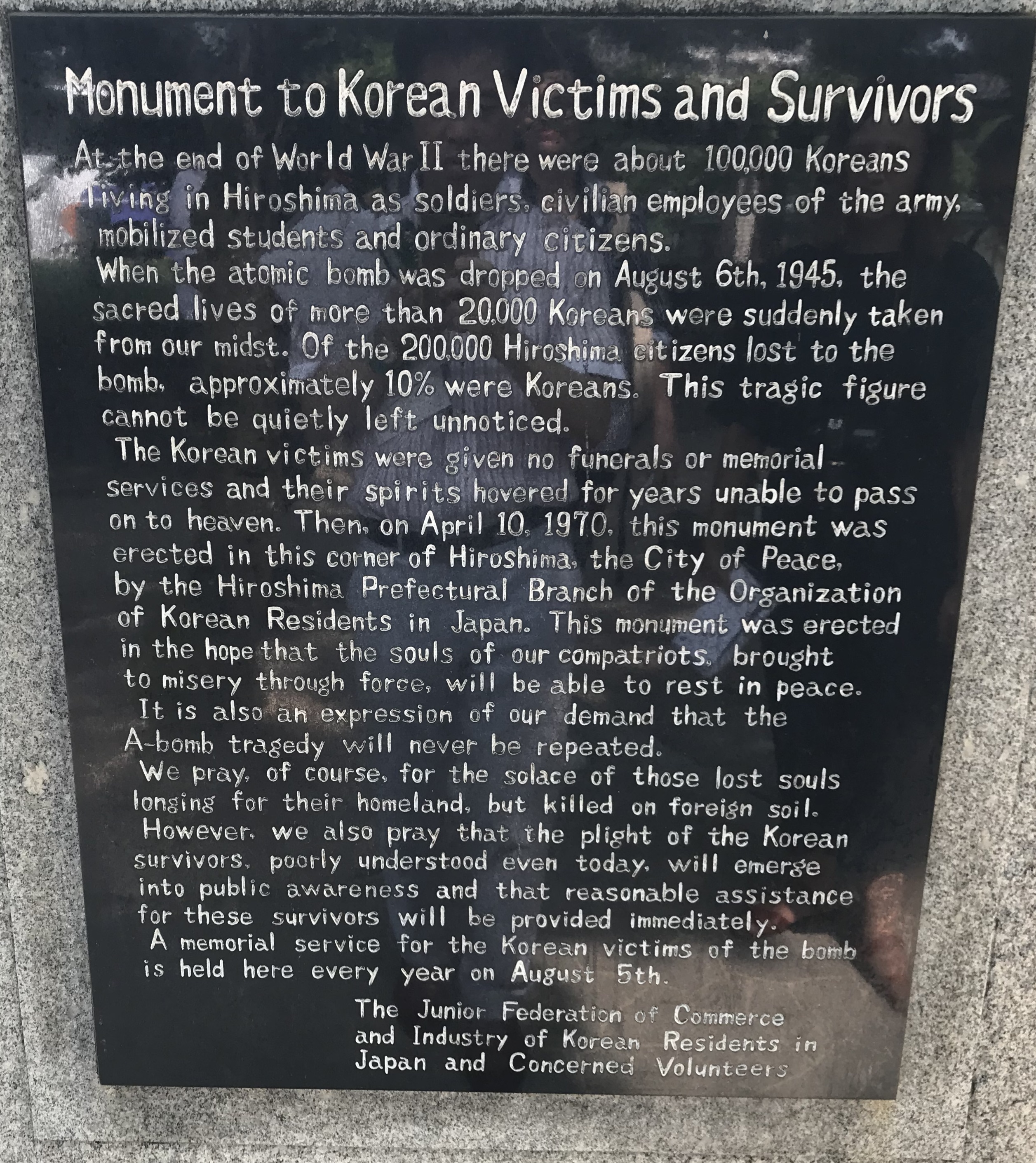

The inscription on the stone tower says, “When the atomic bomb was dropped on August 6th, 1945, the sacred lives of more than 20,000 Koreans were suddenly taken from our midst. Of the 200,000 Hiroshima citizens lost to the bomb, approximately 10% were Koreans. This tragic figure cannot be quietly left unnoticed.”

The full inscription on the Monument in Memory of the Korean Victims of the A-bomb in Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park. Photo by Takahashi Kosuke.

“The South Korean president’s visit to the cenotaph is something that we Koreans in Hiroshima have been long wishing for, so we are very happy now,” Kwon Joon-oh, 73, a second-generation A-bomb survivor, told The Diplomat on May 12.

“Prime Minister Kishida has been criticized for his lack of apology in Seoul, but I think that even if he doesn’t directly say an apology, visiting the monument itself represents an apology,” said Kwon, who serves as vice chairperson of a special committee for atomic bomb victims in the Hiroshima office of the Korean Residents Union in Japan (Mindan). The Hiroshima branch of Mindan was the group responsible for erecting the monument in 1970 and still manages it today.

“This monument was erected in the hope that the souls of our compatriots, brought to misery through force, will be able to rest in peace,” the inscription states. “However, we also pray that the plight of the Korean survivors, poorly understood even today, will emerge into public awareness…”

Kwon strongly hopes Yoon will hold a face-to-face meeting with South Korean A-bomb survivors living in Hiroshima during the G-7 summit.

“Japan’s foreign ministry is basically in control of the G-7 leaders’ schedule, so President Yoon may not have time to meet us,” Kwon said with a mixture of anticipation and dread.

The monument’s epigraph reads, “The Monument in Memory of the Korean Victims of the A-Bomb: In memory of the souls of His Highness Prince Lee-Woo and over 20,000 other souls.” The prince was a nephew of Prince Lee-Eun, also known as Yi Un, the last crown prince of the Joseon Dynasty.

Prince Lee-Woo (also knows as Yi U) came to Japan in 1922 to receive education as a military man. He was lieutenant colonel in the Second General Army located in Hiroshima in August 1945. He was riding his horse to work when the bomb exploded. He fled westward, but by the time he reached the west end of Honkawa Bridge, he was no longer able to move. He died the next day.

In 1970, the monument to Korean victims of the atomic bombing was originally erected near the place where the prince was found dead.

However, in the 1980s, people began to question why the monument was outside of the Peace Memorial Park, with critics saying the location symbolized ethnic discrimination. The memorial was relocated to Peace Memorial Park in response to strong requests from the Mindan, as well as citizens and students on school excursions.