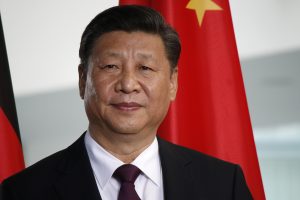

The Diplomat author Mercy Kuo regularly engages subject-matter experts, policy practitioners and strategic thinkers across the globe for their diverse insights into U.S. Asia policy. This conversation with Chun Han Wong – China correspondent at the Wall Street Journal, Pulitzer Prize finalist, and author of “Party of One: The Rise of Xi Jinping and China’s Superpower Future” (Avid Reader Press 2023) – is the 367th in “The Trans-Pacific View Insight Series.”

Explain how the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) made Xi Jinping, and how Xi is remaking the party.

Xi Jinping is inseparable from the Communist Party. “Born red” into a revolutionary family, he grew up within the party’s byzantine inner circles and has known no other political power in China. His formal education was disrupted by Mao Zedong’s Cultural Revolution, but Xi received a first-class education in politics. He saw up close how the bureaucracy functioned; how the revolutionary elite behaved; and how leaders accumulated, exercised, and, in some cases, lost power.

Even when many of his generation turned their backs on an institution that ravaged their youth, Xi showed a sense of noblesse oblige, joining the party after repeated rejections and pursuing a political career at a time when it offered few of the material benefits that it would later be associated with.

While some observers liken Xi to a second coming of Mao, citing similarities in style and rhetoric, this comparison falls short in explaining Xi’s approach to governance. The chaos of the Mao era seemed to imbue Xi with a strong desire for control. Whereas Mao could mobilize the masses and circumvent the party bureaucracy, often lurching toward disastrous radicalism, Xi exercises his power through the party machinery. Since taking power in 2012, Xi has become Communist China’s most prolific codifier of state laws and party regulations. He enforces political loyalty and public order punctiliously, using the party’s disciplinary and security apparatuses. The party of Xi, as he hopes to make it, is unapologetically Leninist – a disciplined, driven, and united political force that unswervingly executes leadership directives.

Identify the key factors and people shaping Xi’s leadership style and worldview.

Memoirs, interviews and writings by members of the Xi clan and their associates show that Xi Jinping regards his late father, the revolutionary elder Xi Zhongxun, as a key influence. These accounts memorialize the elder Xi as an austere parent and committed cadre who believed that “the party’s interests come first” – a principle that the younger Xi has carried forward in his efforts to restore the Communist Party’s centrality in China. Other prominent politicians of his father’s generation – including Geng Biao, China’s defense minister in the early 1980s – also mentored Xi Jinping during his early career, shaping his perspectives on political, military, and economic affairs.

More recent influences include Wang Huning, an academic turned party theorist who has argued that a powerful, highly centralized state is essential for governing a vast and diverse China. Wang has also styled himself an astute analyst of the West, most notably in a 1991 book, titled “America Against America,” where he compared American democracy and individualism unfavorably with Chinese cultural norms – views that now appear to animate Xi’s domestic and foreign policies. Wang continues to wield significant policy influence in his second term in the party leadership, notably keeping his seat as a deputy head of a powerful party commission overseeing economic and governance reforms.

Analyze the parallels between the rise of Xi as supreme leader and China as a superpower.

Over his decade in power, Xi has imposed himself as China’s preeminent leader and restored the Communist Party’s dominance over society. He treads a similar path on the global stage, presenting himself as China’s face to the world and a leading statesman who can provide a stabilizing influence during tumultuous times. Xi’s strongman persona at home runs parallel to the image he seeks for his country abroad – confident, forceful, and unflappable in the face of stern challenges. This carefully crafted profile also feeds the nationalistic fervor that Xi fans for his leadership and Communist Party rule.

The transition to Xi’s forward-leaning posture from his predecessor Hu Jintao’s understated demeanor reflects, in both style and substance, China’s changing stature in early decades of the 21st century. To be sure, China was already growing more assertive during the Hu years, but Xi has proven much more effective in projecting this fast-rising power’s strength and reach. Xi confronts pushback against his agenda on both domestic and international fronts, but he has not and, arguably, cannot countenance any retreat that could undermine his standing.

Evaluate Xi’s effectiveness in harnessing “discourse power” to frame China’s narrative and national identity vis-à-vis the West.

Xi asks a lot of his charges when it comes to flexing China’s global influence, but the results appear mixed at best. The Communist Party’s tactics for shaping domestic narratives often don’t translate well abroad, and the hawkish instincts that Xi inspires across the party similarly prove counterproductive. The aggressive “wolf warrior” ethos that has defined Chinese diplomacy under Xi continues to jar Western audiences – most recently when Beijing’s ambassador in Paris, Lu Shaye, questioned the legitimacy of post-Soviet states and caused backlash in Europe.

An Africa specialist earlier in his diplomatic career, Lu had written essays arguing that China must do more to flex its “discourse power,” seize the microphone from the West, and win friends across the developing world. But the Manichean lens through which many Chinese – and Western – officials view the other side isn’t self-evident nor does it necessarily resonate elsewhere. Many countries want sound and stable relations both with China and the West, and hope to see Beijing and Washington reach a new modus vivendi that can keep their strategic rivalry from boiling over.

Xi seems to understand this and has signaled a desire to rein in the most lupine aspects of Chinese diplomacy, but the core elements won’t change – a confident China will continue staking its place as a global power and never shy from a fight.

Assess the long-term impact of Xi’s efforts to influence CCP leadership succession on China’s superpower future and relations with the United States.

Governing for a third term without a clear successor in place, Xi is set to remain in power for the foreseeable future. His vision for China and its place in the world will likely continue shaping Beijing’s foreign policy and its interactions with Washington for many years to come.

From what we know of Xi’s personal views, going back to his days as a junior official, he doesn’t appear to harbor any deep-seated animosity toward the United States. He has interacted amicably with American interlocutors over the years, spoken privately of his liking for Hollywood movies and, in the early 2010s, even sent his daughter to study at Harvard University. Nonetheless, Xi, as paramount leader, has demonstrated a firm belief that the U.S. is as relentless in defending its hegemonic dominance as China is in chasing its national renaissance.

Xi and his lieutenants often say that “the East is rising and the West is declining,” a mantra that plays well domestically and also reflects genuine elite attitudes. Any successor that Xi chooses, assuming the transition plays out the way he wants, would almost certainly carry forward this approach to strategic affairs.