The world is moving towards green, low-carbon development. Green investments are growing constantly. In 2022, investments in the global energy transition exceeded $1 trillion and, for the first time ever, were equal to fossil fuel production costs. Renewable energy sources attracted one of the largest shares of capital. Growing interest in the global green agenda could help developing countries attract international support through climate-related expertise and financing.

Climate change is a crucial issue for Central Asia. The region is among the most vulnerable to climate change. Central Asian economies face two types of climate-related risks. Regarding physical risks, there are adverse climate change consequences in the region such as the drying of the Aral Sea, a shortage of water resources, food security risks, and increased frequency of extreme weather events. Climate change is becoming an increasingly severe challenge for the Central Asian agriculture sector. Transition risks (related to regulatory changes in global markets) are also significant for the region. After the imposition of the EU carbon border tax in 2026, Kazakhstan exporters may lose up to $250 million in revenues per year.

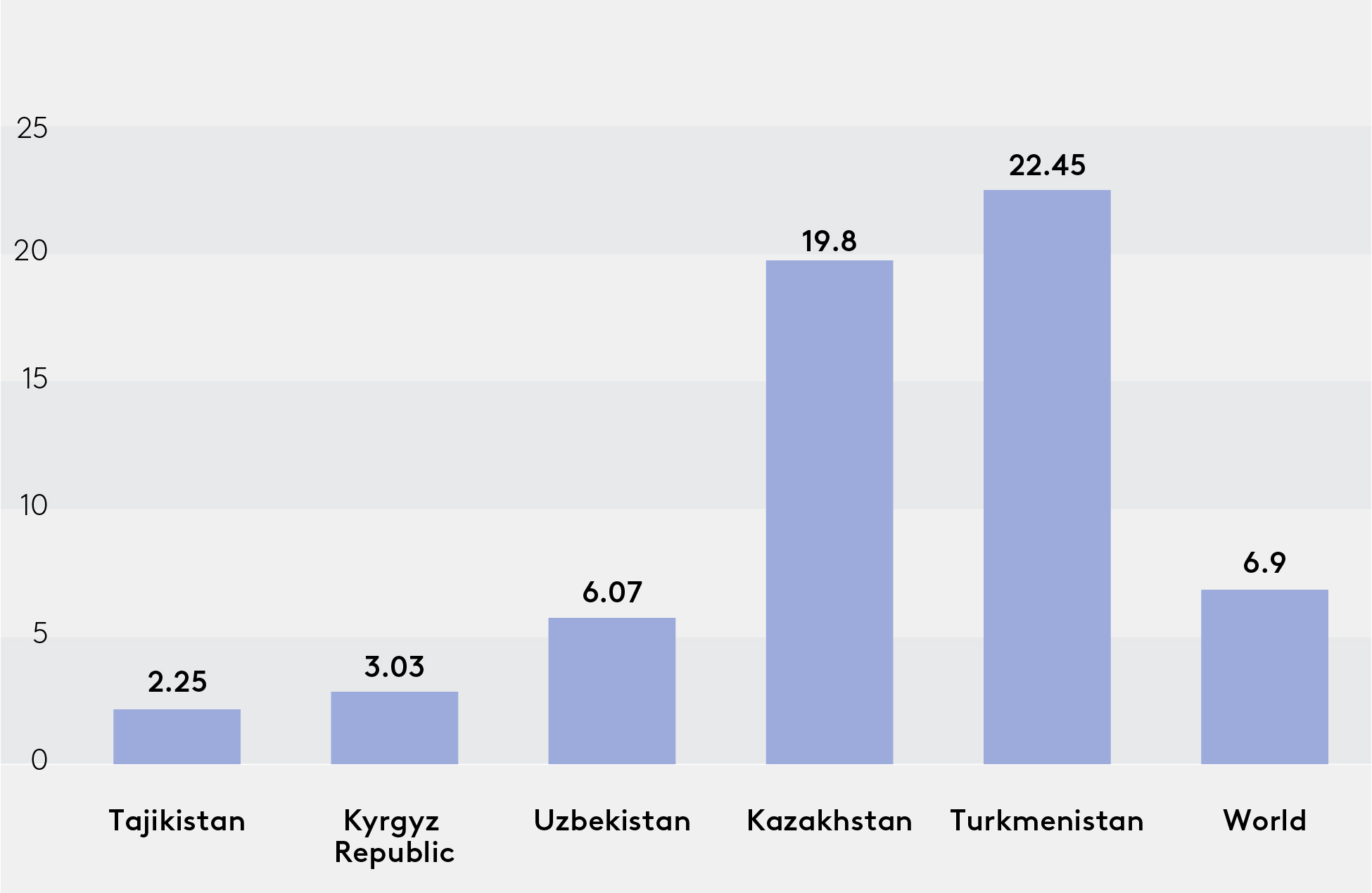

The levels of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions differ significantly among Central Asian countries. The exports of Turkmenistan and Kazakhstan are highly dependent on hydrocarbons, and as a result, they produce high GHG emissions (22.45 and 19.8 CO2 equivalent tonnes, respectively) through fugitive emissions. Conversely, the Kyrgyz Republic and Tajikistan demonstrate the lowest levels of GHG emissions (3.03 and 2.25, respectively) due to their substantial reliance on hydropower in the energy sector.

Per-capita greenhouse gas emissions in CO2 equivalent, tonnes, 2021

Source: Our World in Data.

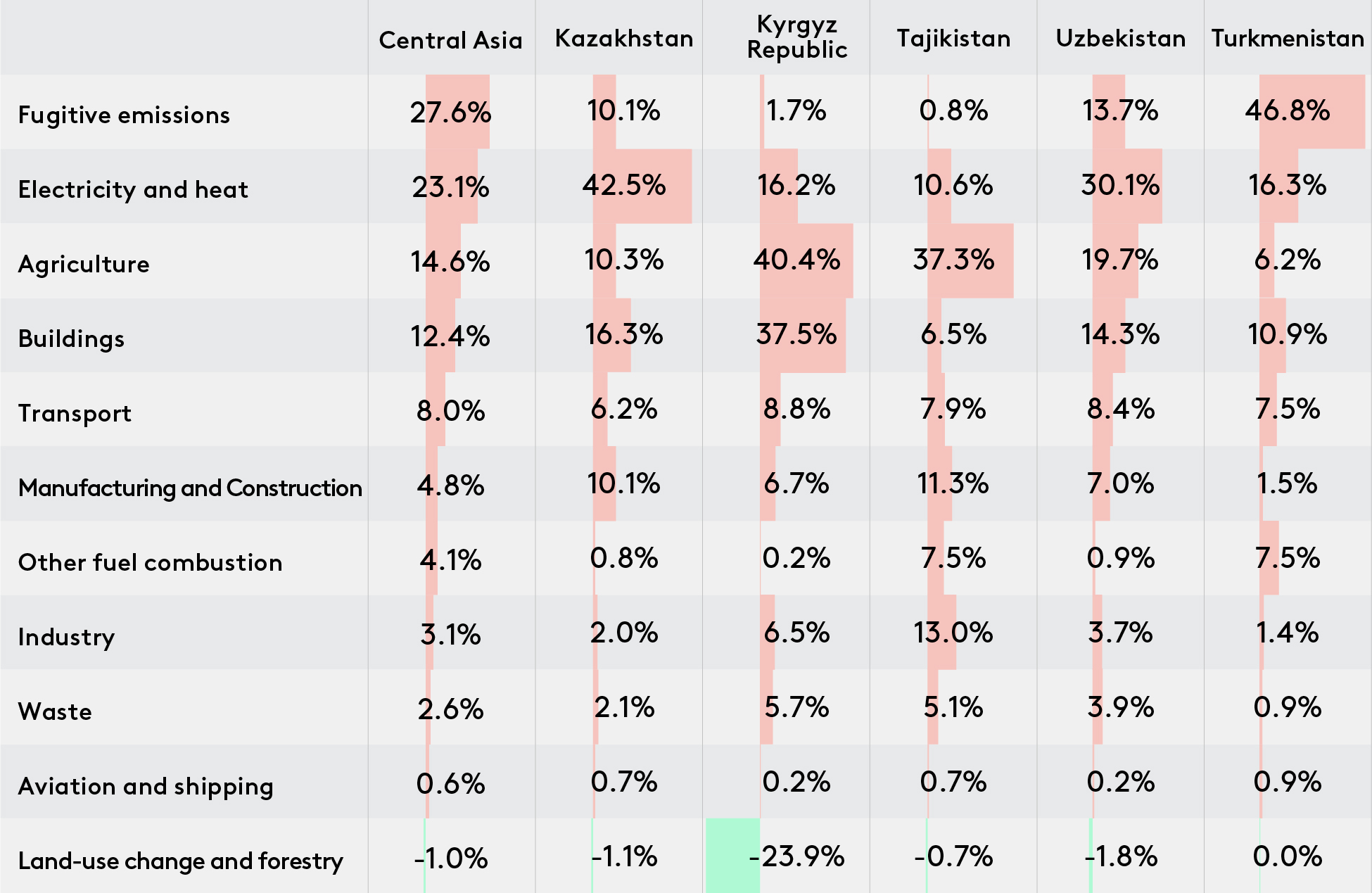

There are four key “pain points” in the region’s sectoral structure that produce the highest volume of GHG emissions and should be in focus: fugitive emissions, electricity and heat production, agriculture, and buildings. These sectors produce about 80 percent of GHG emissions in Central Asia. Coal-fired power generation continues to account for a significant share of the region’s total greenhouse gas emissions. It leads to high emissions in the electricity and heat production and buildings sectors. For example, the electricity and heat sector produces 42.5 percent of GHG emissions in Kazakhstan, while buildings account for 37.5 percent in the Kyrgyz Republic.

Greenhouse gas emissions by sector in CO2 equivalent, 2019

Source: EDB calculations based on Climate Watch.

The region needs more investment in the development of new generation capacity, including hydro power plants, solar and wind power plants, the construction and upgrade of water treatment facilities, and so on. Climate finance instruments provided by multilateral development banks (MDBs) for adaptation and mitigation could further boost the low-carbon transformation of the region.

Aside from financing, the MDBs may also help develop climate projects and assess climate risks and opportunities. They can arrange syndicated loans, provide technical assistance, share the expertise required for feasibility studies, mitigate risks or offer guarantees for their reduction, and this will encourage private investment in green projects. They also focus on ways to see whether climate finance or ESG practices are effective and create long-term impact. MDBs’ cooperation on these issues is also important.

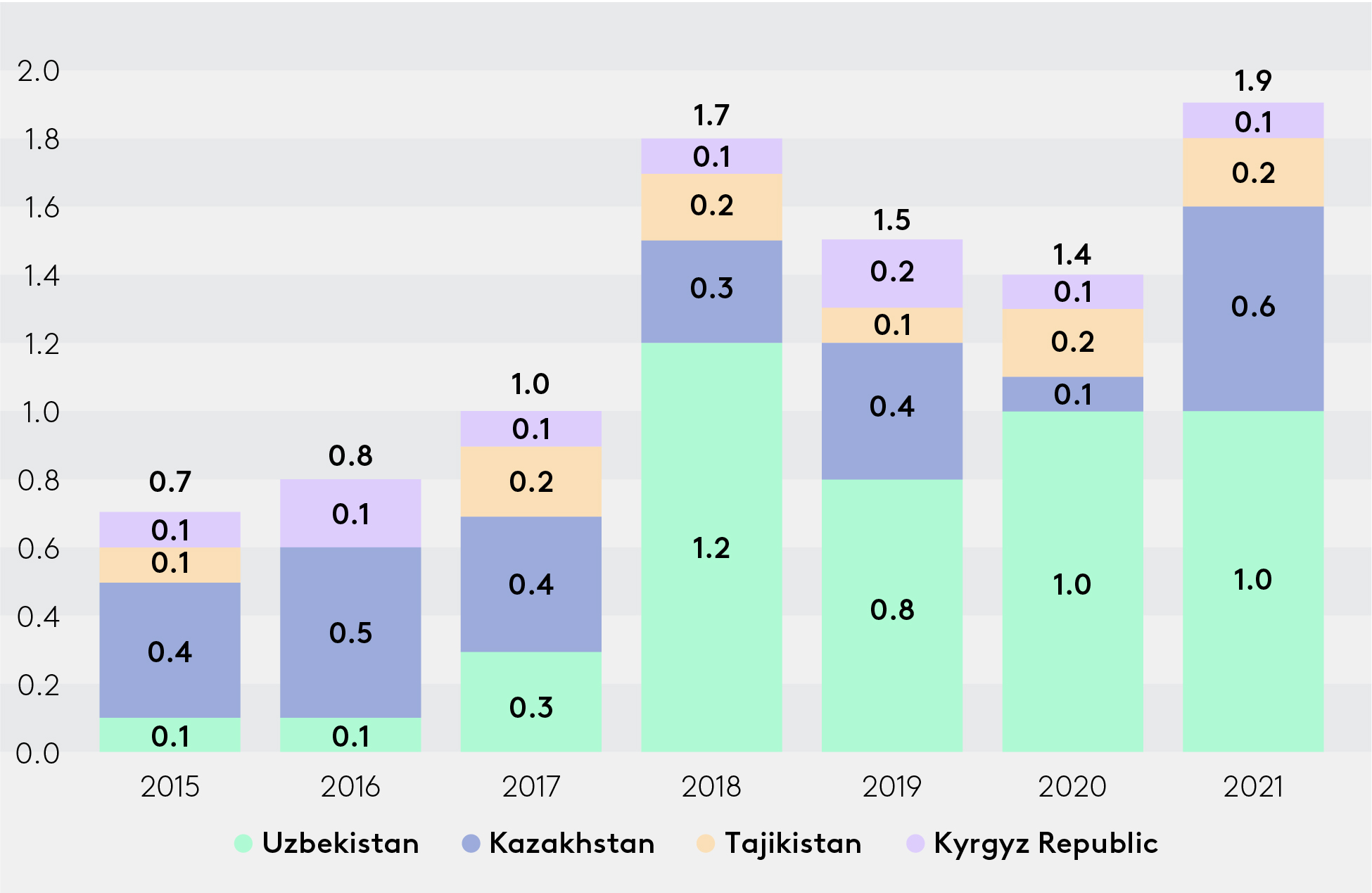

In 2021, major MDBs provided more than $81.7 billion in climate finance worldwide, of which $50.7 billion was channeled to low- and middle-income countries. In 2021, Central Asian countries received $1.9 billion in climate finance, or 2.2 percent of the total amount, in comparison with Central Asia’s 0.4 percent share of global GDP. From 2015 to 2021, Central Asia obtained $8.9 billion from MDBs as green finance. In particular, Uzbekistan received almost half of the total amount – $4.4 billion (49.1 percent). Reforms initiated in Uzbekistan in 2017 (currency and price liberalization, customs and tax reforms, etc.) drove up the incoming flows of climate finance. Kazakhstan received $2.6 billion (29.4 percent), Tajikistan received $1.1 billion (12.1 percent), and the Kyrgyz Republic received $0.8 billion (9.2 percent). Turkmenistan received almost nothing (0.2 percent).

Central Asian countries could attract more external climate finance due to the region’s high physical climate risk. Without external sources, the green transformation of Central Asia will be a burden for national budgets. Implementing green projects, low carbon technologies, and digital solutions to prevent climate change and protect the environment are highly capital-intensive measures. For example, estimates suggest that the countries of the region may face costs ranging from 100 percent of national GDP (Kyrgyz Republic) to 300 percent (Kazakhstan) in order to achieve carbon neutrality. There are some ways, however, to attract green finance to the region for its low-carbon transformation.

First, the countries could provide more high-quality bankable projects and develop connections with MDBs operating in the region. For example, Turkmenistan has enormous potential to expand ties with MDBs, in particular for upgrading the extractive industry and reducing fugitive emissions. Uzbekistan could serve as a successful example of how Central Asian countries work with MDBs.

Second, the Central Asian governments could focus on investments in renewable energy sources. Central Asia has great potential for hydro, solar, and wind power generation. At the same time, the countries should continue to develop balancing power capacities such as gas and nuclear generation. In particular, Central Asia has huge potential to develop nuclear power generation, inasmuch as Kazakhstan is the world’s largest producer of natural uranium and a major manufacturer of nuclear fuel components.

Third, external support could work together with domestic policymaking. National regulation is equally important, such as green taxonomies. For example, Kazakhstan has already adopted its own taxonomy of green projects, while Kyrgyzstan is in the process of developing taxonomies for green finance.

Fourth, supranational support from multilateral institutions could be useful for enhancing regional competencies. For instance, the countries could share regional experience and successfully implemented measures, as well as spreading energy-efficient technologies in the region. Improvement of energy efficiency is key to reducing carbon intensity and should be part of the green transformation strategies of the agriculture, industry, and buildings sectors.

Fifth, moving towards a more regional ESG (environmental, social, and governance) finance market could be helpful to attract private capital to green projects, as well as for issuing ESG bonds. The Astana International Financial Center could ensure the development of green finance policy and green financing instruments both in Kazakhstan and the Central Asian region as a whole.

Finally, governments, international development institutions and the private sector need to work together in combating climate change. Taking control of climate risks would take more financial resources, more effective national policies, and more cooperation. Then it could become a valuable factor for long-term sustainable economic growth.

MDBs’ total climate finance of Central Asian countries, $ billion