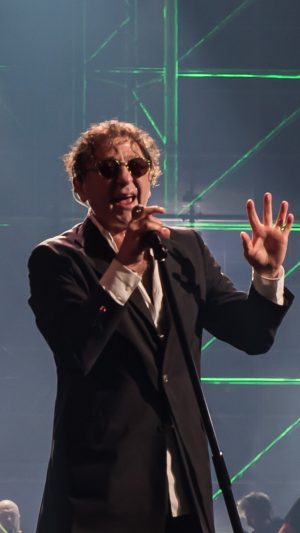

On July 6, the Ministry of Culture and Tourism of Uzbekistan announced that the concert of Grigory Leps, a Russian singer and songwriter, was canceled due to “some technical issues.” Leps, who openly supports Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, was supposed to perform on October 23 at the “Friendship of Nations” Palace in Tashkent. But news about his performance caused a wave of criticism among citizens of Uzbekistan.

Earlier, his manager, Vladimir Yuriupin, boasted, “We can do without Kazakhstan” after Leps’ concert scheduled for July 8 in Almaty, Kazakhstan, was boycotted and then canceled. Soon after, Kyrgyzstan followed suit, canceling Lep’s August 2 performance in Cholpon-Ata. And now Uzbekistan is off the schedule.

Is it over for “Z-artists” – Russian stars supportive of Moscow’s war in Ukraine – in Central Asia?

Leps is not the first Z-artist to have performances canceled in Central Asia. Since the start of the Russia-Ukraine war in February 2022, a number of shows and concerts have been canceled.

Z-artist Polina Gagarina, was scheduled to perform in Astana, Kazakhstan, in February 2023, but the show was canceled in November, 2022. Earlier this year, the Zhara music festival scheduled for March 9-12 in Kazakhstan was first forced to move to Uzbekistan. Netizens of Kazakhstan had begun a boycott of the festival because a number of organizers and participant Russian performers were supporters of the Kremlin’s war in Ukraine. Allowing them to perform in Kazakhstan would mean “supporting the war in Ukraine,” as social media users maintained. The festival was rescheduled for May 20-21 at “New Uzbekistan” Park, Tashkent.

“As an ordinary citizen, I have chosen my side,” Mirzo Zominiy, a citizen activist from Uzbekistan, told The Diplomat. He started an online boycott against Zhara with the hashtags #StopKremlinPropaganda and #StopZArtistsConcerts. “Uzbekistan is neutral [in the Russia-Ukraine war]. But I am on the side of Ukraine. I am against the fact that another country invades [Ukraine’s] sovereign territory with a terrorist act, occupies its land and exterminates its people.”

The Zhara festival was ultimately canceled.

Uzbekistan’s government keeps a neutral position on the war. Before Leps’ concert was officially canceled, Deputy Minister of Culture and Tourism of Uzbekistan Bahodir Ahmedov addressed the calls for a boycott. “Uzbekistan has not closed its doors to any artist. They come, perform their art, receive applause, and leave. … There are no obstacles to art in Uzbekistan,” he said.

Ahmedov’s comments were met with a clear reproach from Ukraine’s embassy in Uzbekistan. “[T]he performances of pro-war Russian artists in Uzbekistan may create a false appearance of their support for criminal activities aimed at inciting war, which threatens the reputation of the Republic of Uzbekistan,” the embassy said in a Facebook post. It also mentioned that the funds from performances might be used to finance atrocities against the Ukrainian people.

Private restaurants and bars in Tashkent, however, continue hosting Russian performers.

Russian singer and blogger Instasamka gave a concert in mid-June this year at a restaurant, TOKU. Instasamka is listed by the Kyiv-based non-governmental website Myrotvorets (Peacemaker) which maintains a running list of “enemies of Ukraine.” Although news about a donation by Instasamka to the Russian army was found to be fake, the website still keeps her on its list as a “provocateur” who takes part in the “propaganda of Russian Nazism, fascism and strong Kremlin values” and provides “information support for the open attack of fascist Russia on Ukraine.”

Another Z-artist, Irina Dubtsova, was supposed to perform at the Obi Hayot restaurant on June 25, but after a popular Uzbek-Russian singer Nargiz criticized the show, the concert was canceled. Nargiz, who gained popularity in Russia and moved back to Uzbekistan after she criticized the Kremlin’s “special military operation,” continues to speak out against the Russian performers visiting Tashkent.

While Central Asian states have been distancing themselves from Moscow since the start of the war, public opinion on Russia’s ongoing invasion of Ukraine remains divided. A small-scale poll (involving 1,500 people in each country) conducted last spring by Central Asia Barometer showed that 30 percent of respondents from Kazakhstan, 34 percent from Kyrgyzstan, and 47 percent from Uzbekistan believed that Russia’s “special military operation” in Ukraine was “completely” or “somewhat” justified; 44 percent Kazakh respondents, 36 percent of Kyrgyz and only 16 percent of Uzbeks thought the operation was somewhat or completely unjustified. The second wave of the survey in fall 2022 also found that 39 percent of respondents from Kyrgyzstan and 31 percent of respondents from Kazakhstan blamed Ukraine or the United States for the war.

This perception, however, might have changed, at least a little, in favor of Ukraine since the second wave. A survey conducted among 1,100 people in Kazakhstan in May 2023 by Kazakh research groups MediaNet and PaperLab revealed that only 12.8 percent of respondents supported Russia while 21.1 percent supported Ukraine. At the same time, anxiety over a possible Russian invasion of Kazakhstan has risen from a mere 8 percent in the previous cycle of polls to 15 percent in May.

It is hard to find polls from Uzbekistan. In general, we can observe three groups of people, noted Zominiy: “The segment of the population with a common sense – people who care about Uzbekistan’s politics, its independence, the neutrality, and international image, [as well as about the] pride and honor of the population. There is a group of bland and indifferent people. And there are ardent pro-Kremlin people and bots.”

There is another layer of the society – the religious community. For them, standing against or for war does not matter. They pay attention to morality and oppose concerts as such from religious and morality perspectives.

While judging public opinion of the war, it is worth keeping in mind two important factors. First, Russian media propaganda has a large audience in Central Asia. Central Asia Barometer’s above-mentioned poll shows that 64 percent of respondents from Kazakhstan, 65 percent from Kyrgyzstan, and 6 percent from Uzbekistan watch news and entertainment from Russia. Second, Russia still remains the most favorable destination for millions of labor migrants from Central Asia. During the first quarter of 2023, Russia welcomed 630,859 labor migrants from Uzbekistan, 349,357 from Tajikistan, 172,591 from Kyrgyzstan, and 34,783 from Kazakhstan.