The Diplomat author Mercy Kuo regularly engages subject-matter experts, policy practitioners and strategic thinkers across the globe for their diverse insights into U.S. Asia policy. This conversation with Dr. Alicja Bachulska – policy fellow at the European Council on Foreign Relations, Warsaw office and research fellow at CHOICE – is the 376th in “The Trans-Pacific View Insight Series.”

Explain Beijing’s agenda in prolonging negotiations with Moscow over the Power of Siberia 2 pipeline.

It seems probable that China believes that time is on its side. The war in Ukraine and Western sanctions against Russia are not going to end anytime soon, and for Beijing, this translates into a stronger bargaining position vis-à-vis Moscow. China continues to support Russia diplomatically and economically, and the Chinese Communist Party is very much aware of the growing asymmetries between Moscow and Beijing, which work to the detriment of the former. From this perspective, China is trying to leverage its position in prolonging negotiations over the Power of Siberia 2 pipeline. While pricing is one of Beijing’s concerns, there are also other factors at play, such as China’s own plans to diversify its energy sources, with Beijing wanting to avoid overreliance on one single partner. Moreover, China is rolling out its own green transition, so the Chinese leadership might be unsure how much Russian gas it will need in the medium to long term.

How does Beijing’s upper hand reflect power dynamics between China and Russia?

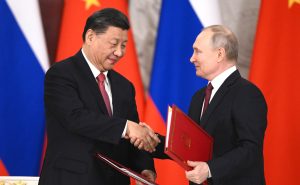

While Beijing is now Moscow’s most influential and internationally renowned partner, Russia is not necessarily becoming a straightforward “vassal” of China. Power dynamics between the two countries are much more complex than that. Although Moscow increasingly counts on Beijing when it comes to its economic performance, China’s overall share in Russia’s trade remains relatively small. The same applies to Chinese investment in Russia. Moreover, Moscow possesses some know-how and technology that Beijing finds extremely valuable, such as the technology to produce aircraft engines, crucial to China’s military modernization. This means that Putin still has quite a lot of leverage in his negotiations with Xi. Even though many in China perceive Russia as unpredictable and Sino-Russian relations as far from perfect, the shared goal of weakening the U.S.-led international order continues to bind the two countries together.

What is the impact of President Putin’s protracted war in Ukraine on Chairman Xi Jinping’s calculus toward the future of Putin’s leadership?

China’s initial reaction to Putin’s aggression suggests that Beijing might have believed Moscow’s narrative on the “special military operation.” In other words, China expected it to be quick and successful, with a decisive victory achieved within days of the invasion. In retrospect, this could have been a miscalculation on Beijing’s side. Nevertheless, although Russia’s overall weakness and Ukraine’s strength might have come as a surprise to many in China, the development of a protracted war has not fundamentally changed Beijing’s strategic calculus. China does not want to see a seriously weakened Russia, since regime change in Moscow could translate into far-reaching destabilization on China’s own border. It could also constitute a huge gain for the West. Xi and Putin share the same worldview, in which Western liberal democracies led by the U.S. present an existential threat to the current regimes in Beijing and Moscow, thus pushing the two leaders even more closely together in their shared fight to rebuild the post-cold war global order. That is also why Xi Jinping is unlikely to change his approach towards Putin any time soon.

Examine the approach of Visegrad 4 to managing the China-Russia power play in Central Eastern Europe.

Given Hungary’s visibly pro-Russian stance, there is no unified approach towards managing China-Russia relations in the Visegrad 4 countries. While Poland, Czechia and Slovakia now see China as an enabler of Russian aggression, Hungary remains the region’s Trojan horse. Beyond Visegrad 4, however, many Central and Eastern European (CEE) countries seem to be at the forefront of a more assertive debate about the future of Europe-China relations. Sino-Russian strategic cooperation, their shared opposition to NATO and other U.S.-led institutions, as well as Beijing’s unwillingness to condemn Moscow’s aggression have drastically altered the perception of China in the CEE region, most profoundly in the Baltic states, Poland, and Czechia. Beijing is now seen as an actor with ambitions to reshape the European security architecture in line with Moscow’s interests, which essentially puts China at odds with many in Central and Eastern Europe. This is also one of the factors behind the recent intensification of informal ties with Taiwan. Given the history of anti-authoritarian and anti-communist struggles in CEE, Taiwan’s resilience strikes a familiar chord among some political elites and the public more broadly, especially in countries such as Czechia.

Assess the competition for influence in Europe between the U.S.-EU leadership and the China-Russia partnership.

These kind of binary terms might not necessarily reflect the reality on the ground in Europe. While the consensus within the broader political debate is that transatlantic cooperation is the fundamental basis of European security and stability, the degree to which it is seen as a priority vis-à-vis the implications of Sino-Russian cooperation varies from country to country. Some states, such as France, believe that striving toward “strategic autonomy” should be a priority for Europe, while others, such as most CEE countries, tend to focus on the immediate implications of war and the fact that the US remains the sole security guarantor on the continent. In this context, the sense of urgency when it comes to dealing with the effects of Sino-Russian cooperation on the security situation in Europe is disproportionately accentuated by CEE members of the EU rather than their Western counterparts. These kinds of diverging views accentuate the existing tensions within Europe and enable China to drive a wedge between the “old” and the “new” EU member states.