Vietnam’s government has requested social media platforms to use artificial intelligence models in order to automate the detection and removal of politically sensitive online content, its latest attempt to control what information flows through the country’s digital networks.

The request, which was reported by Reuters (via state media) on Friday, requires platforms like Facebook, TikTok, and YouTube to coordinate with authorities to stamp out content deemed “toxic.” This designation, in Reuters’ paraphrase, includes “offensive, false, and anti-state content.” The order was made during the Ministry of Information’s mid-year review.

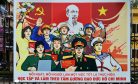

The request is just the latest sign of the Communist Party of Vietnam (CPV)’s desire to narrow the scope of social media platforms to be used to stir up dissent. Unable or unwilling to block these platforms outright, as is the case in China, the CPV authorities have nonetheless attempted to keep them on a tight leash.

Over the past few years, Vietnam has increased its pressure on social media networks to remove politically sensitive content – a flipside to the political clampdown that has seen dozens of independent journalists and human rights defenders arrested and sentenced to heavy prison terms.

In 2018, it passed a cybersecurity law that forces Facebook and Google to take down posts deemed to be threats to national security within 24 hours of receiving a government request. To show it was serious, the government at one stage even threatened to throttle access to Facebook if the company did not comply with its demands.

Given Vietnam’s importance as a digital market –the country has the seventh-largest national pool of Facebook users in the world and the sixth largest on TikTok – the tech giants have generally been responsive to government requests that it take down “offensive” content. As Nguyen Khac Giang and Dien Nguyen An Luong wrote in a recent paper for the ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute, “Vietnamese authorities have become increasingly adept at exploiting their economic leverage to arm-twist Big Tech into compliance.”

According to Facebook’s own data, the platform removed nearly 2,000 pieces of content in 2021, and a further 984 in the first half of 2022 – the most recent figures available. Most of them were removed for, in Facebook’s words, “allegedly violating local laws on providing information which distorts, slanders, or insults the reputation of an organization or the honor and dignity of an individual.”

At its mid-year conference, the Ministry of Information claimed that during the first half of this year, Facebook removed 2,549 posts, while YouTube removed 6,101 videos and TikTok took down 415 links – all following government take-down requests. In late 2020, Amnesty International claimed that Facebook and YouTube were responsible for “censorship and repression on an industrial scale” in Vietnam.

In addition to take-down requests, Vietnam has also erected a sturdy legal framework to keep the online sphere under tight control. It has forced foreign tech firms to establish representative offices in Vietnam and store users’ data locally and is preparing new rules to limit which social media accounts can post news-related content.

In May, the government announced that it would be mandatory for users of Facebook, TikTok, and other social media networks to verify their identities, citing the need to combat online scams and other forms of online crime – a category within which the CPV includes political dissent of various degrees. Around the same time, the CPV announced an investigation into the social media app TikTok, which is massively popular among the young and is beginning to challenge Facebook as the country’s preferred social media network.

The state media report cited by Reuters did not give details on when and how these platforms had to abide by the new requirement. It is not clear if it even represents much of an advance on the existing controls. It nonetheless represents a further tightening of the ratchet in terms of the CPV’s control of the online sphere, and his efforts to ensure that the agenda of Big Tech conforms to its own.