The challenges of mounting debt and climate change have emerged as two of the most pressing issues for developing countries, and Sri Lanka is no exception. The global economy currently faces serious debt distress, and developing countries are pressed to find innovative solutions that address both climate and debt crises under the constraints of the current global financial architecture.

At the 2023 Summit for a New Global Financing Pact, Sri Lanka’s President Ranil Wickremesinghe called for a “separate, innovative process for middle-income countries” to address their debt challenges, and advocated for “timely and automatic access to concessional financing.” In addition, Wickremesinghe called for multilateral development banks and international financial institutions to discover better solutions for providing emergency financing for countries in debt distress, adding that macroeconomic reform is essential.

During the World Economic Forum’s Annual Meeting of the New Champions, Sri Lankan Foreign Minister Ali Sabry emphasized the importance of sustainable debt restructuring, particularly for developing countries. Sabry explained that “because of the financial crisis, you can’t put your funding into other important areas such as education, climate change, and renewable energy because you are grappling with your interest and debt payments.”

Sri Lanka’s president and foreign minister have reaffirmed that converging debt and climate vulnerabilities demand new solutions and remain two of their government’s top priorities. However, Sri Lanka must find innovative approaches to sustainable development, for which access to climate finance from developed countries is essential to offset climate-induced inequality.

Climate Debt: The Mismatch Between Climate Change Contribution and Vulnerability

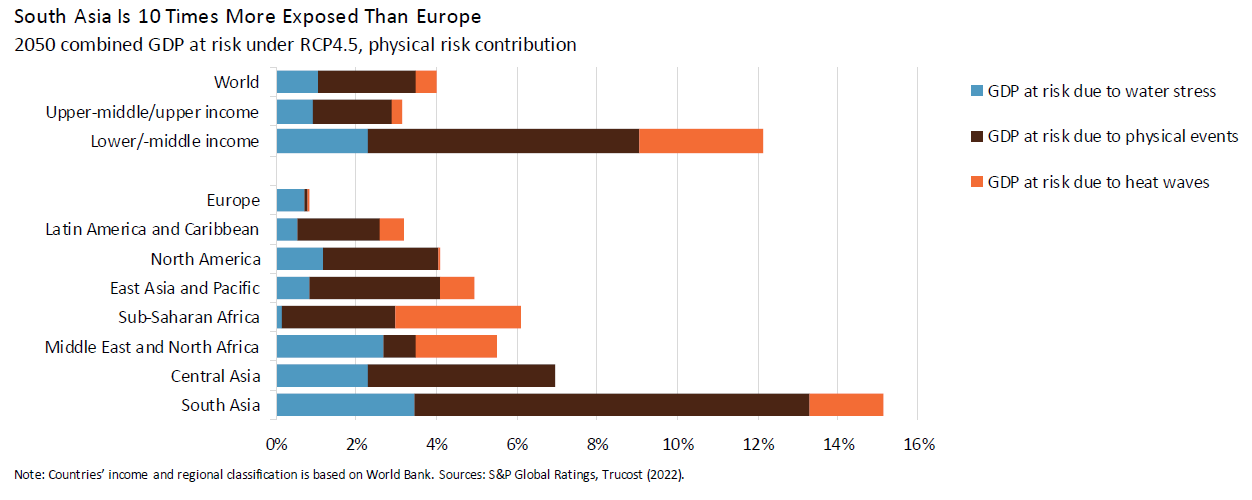

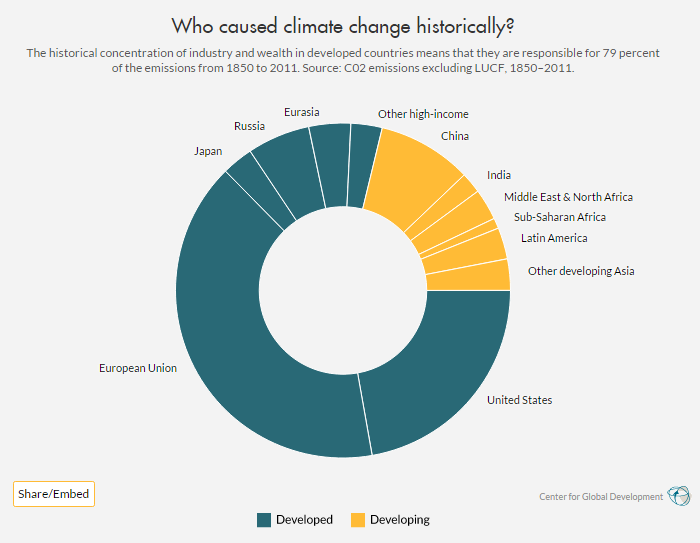

Climate change disproportionately affects the economies of developing countries, with 15 percent of South Asia’s GDP expected to be at risk by 2050. Despite being responsible for only 21 percent of cumulative global carbon emissions, developing countries stand to lose significantly more in climate-compromised GDP. Figures 1 and 2 highlight this asymmetry:

Figure 1: The Contribution of Developed and Developing Countries to CO2 Emissions. Graphic by the Center for Global Development.

Sri Lanka is categorized as “other developing Asia” in Figure 1 and as “South Asia” and “Lower/Middle Income” in Figure 2. These show that Sri Lanka faces disproportionately high economic consequences of climate change relative to its historical contribution, accounting for only 0.03 percent of global cumulative emissions.

Sri Lanka ranks 116th out of 182 countries on the climate vulnerability index, with the World Bank projecting that over 90 percent of Sri Lanka’s population currently lives in possible future hotspots for droughts and floods.

In response to climate vulnerabilities, Sri Lanka established ambitious Nationally Determined Contributions, which include commitments to reduce national greenhouse gas emissions by 14.5 percent and produce 70 percent of electricity through renewable sources by 2030. However, these climate targets are unlikely to be met due to limited fiscal resources, low tax revenues, and high levels of debt distress.

Sri Lanka requires financial support from international creditors to ensure it can mobilize the essential funds for climate-resilient investments and adaptation strategies, which will insulate Sri Lankans from the negative consequences of climate change.

Financing Climate Action

Leading economists and policy experts have called for the reform of the global financial architecture, proposing direct actions that developed countries must take to relieve debt and climate burdens on developing countries. They contend that climate finance instruments are essential for developing countries to address climate vulnerabilities in the face of mounting debt pressures, and developed countries must make this finance accessible through revenue-generating solutions. Funds for climate finance instruments and climate reparations must be made available through essential reforms to the global financial architecture, the fossil fuel industry, and global taxation mechanisms in order to redistribute wealth to fund essential climate-resilient investments in developing countries.

1. Reforming the Global Financial Architecture

Climate and debt vulnerabilities are inherently connected through a vicious cycle of debt and climate crises. Developing countries with high levels of debt are unable to mitigate climate risk, leaving them more vulnerable to the consequences of climate change. This “climate-debt trap” drains an estimated $2 trillion per year in resources from low-income countries. Since 2020, foreign debt repayments have risen by 45 percent, placing Sri Lanka and over half of all low-income countries in debt distress or high risk of debt distress.

Experts argue that the global financial system is structurally ineffective at addressing global debt crises. Enhancing financial solidarity between developed and developing economies requires the establishment of a new multilateral mechanism for sovereign debt forgiveness and cancellation. This should involve better access to concessional finance for developing countries complemented by policy autonomy, rather than imposing conditionalities and prolonging debt repayment periods.

Governments must have access to finance that facilitates a long-term attitude to infrastructure investment with non-revenue-generating benefits, which will reduce the debt pressures on developing countries investing in climate change mitigation. Policies to promote climate finance must create new opportunities for a more sustainable debt environment, without undermining global campaigns for debt justice.

2. Ending Subsidies in the Fossil Fuel Industry

Experts have urged governments to stop funding the fossil fuel industry and redirect this money toward climate finance projects for developing countries. On average, G-20 governments provide $584 billion annually as fossil fuel handouts, such as through price support, public finance, and investments into state owned enterprises.

Experts recommend that the G-20 governments end fossil fuel handouts immediately and reallocate this funding to a “Loss and Damage Fund,” which is set to be activated at the 28th session of the Conference of Parties (COP28) in December 2023. Through this fund, rich industrialized countries, whose economic growth was historically driven by fossil fuel-led industrialization, will provide financial assistance to less-industrialized countries that are disproportionately more vulnerable to the impacts of climate change relative to their industrial contribution. Developing countries’ future growth is inhibited by climate challenges, so these reparations aim to compensate for this loss of economic potential.

3. Reforming Global Taxation Mechanisms

For the first time in 25 years, extreme wealth and extreme poverty are rising simultaneously. Oxfam reports that 63 percent of all new global capital created in the last two years (amounting to $42 trillion) went to the richest 1 percent of society. This increase in global inequality undermines poverty alleviation efforts but also exacerbates climate inequality.

Economists posit that global wealth taxes are an effective solution in redistributing funds and reducing the overdependence on debt for financing development projects in developing countries. They call for incremental changes in extreme wealth taxes beginning at 2 percent, which would generate substantial funds for development and climate funds.

Moreover, it is estimated that $483 billion in tax revenue is lost every year as a result of tax evasion, 78.3 percent of which comes through OECD countries. One proposed solution is transferring the responsibility of tax regulation from the OECD to the United Nations, which would enable the creation of a universal and intergovernmental tax convention.

Furthermore, experts have called for governments to make oil and gas companies pay for the damage that they have caused. It is estimated that the share of emissions of the 21 largest fossil fuel companies from 1988-2022 will result in $5.4 trillion in lost GDP between 2025 and 2050. This comes at a time when the six heaviest-polluting companies made profits of over $354 billion in 2022. Economists promote a “polluter pays” tax on fossil fuel companies, redirecting $200-300 billion annually to environmentally sustainable industries that offset fossil fuel-induced climate damages.

The Way Forward

Experts estimate that implementing the three aforementioned solutions would free up a total of $3.5 trillion annually for global climate action. Just one-fifth of this figure would be enough to finance the loss and damage fund ($400 billion per year), meet the $100 billion per year climate finance target, cover emergency U.N. humanitarian appeals ($52 billion per year), and close the universal energy gap ($34 billion per year).

Sri Lanka’s economic and climate crises demonstrate the need for concessional finance in debt-distressed economies to address climate and debt vulnerabilities simultaneously. It is crucial that the financial system explores new solutions and redirects unproductive capital from debt repayments and subsidies to more effective investments.

This is undoubtedly a difficult process and requires significant investment from developed countries that currently experience fewer direct consequences from climate change, but a longer-term strategy is required to mitigate future damages. Without access to concessional climate finance, developing countries will continue to suffer disproportionately from the consequences of climate change, which will exacerbate future global challenges that will inevitably affect developed countries.

If Sri Lanka – like other vulnerable developing countries – hopes to meet its bold environmental commitments in the face of debt distress, it requires a holistic approach from creditors and policymakers to reallocate finance to areas with the greatest economic potential. The government must explore climate finance instruments, such as green bonds, debt-for-nature, and debt-for-climate swaps, alongside ongoing debt restructuring negotiations, as a means of creating a more sustainable debt environment and generating significant multiplier effects that benefit both the economy and the environment.

This article is based on a longer report published by the Lakshman Kadirgamar Institute of International Relations and Strategic Studies, “Climate Finance: Repairing the Past, Financing the Future.” Access the full report here.