On August 6, Ukraine published a coastal notification, declaring the waters of six Russian ports on the Black Sea – Anapa, Novorossiysk, Gelendzhik, Tuapse, Sochi, and Taman – as a zone of “military threat.” This happened in response to Russia’s exit last month from a deal that had allowed safe export of Ukrainian grain. Moscow announced that it would view all ships heading to Ukrainian ports in the Black Sea as carriers of military cargo, and the countries under whose flags these ships are registered as participants in the war on the side of Kyiv.

The situation escalated significantly after Ukrainian maritime drones struck Russian vessels near Novorossiysk and Kerch in early August. Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy issued a warning that Russia risks losing its ships if it continues to block the Black Sea waters and the export of grain. Sergey Vakulenko, a nonresident scholar at the Carnegie Russia Eurasia Center, wrote recently that the Ukrainian drone attacks on Russian ships near Novorossiysk and Kerch are part of a plan aimed at reducing Russian exports from Black Sea ports, primarily oil.

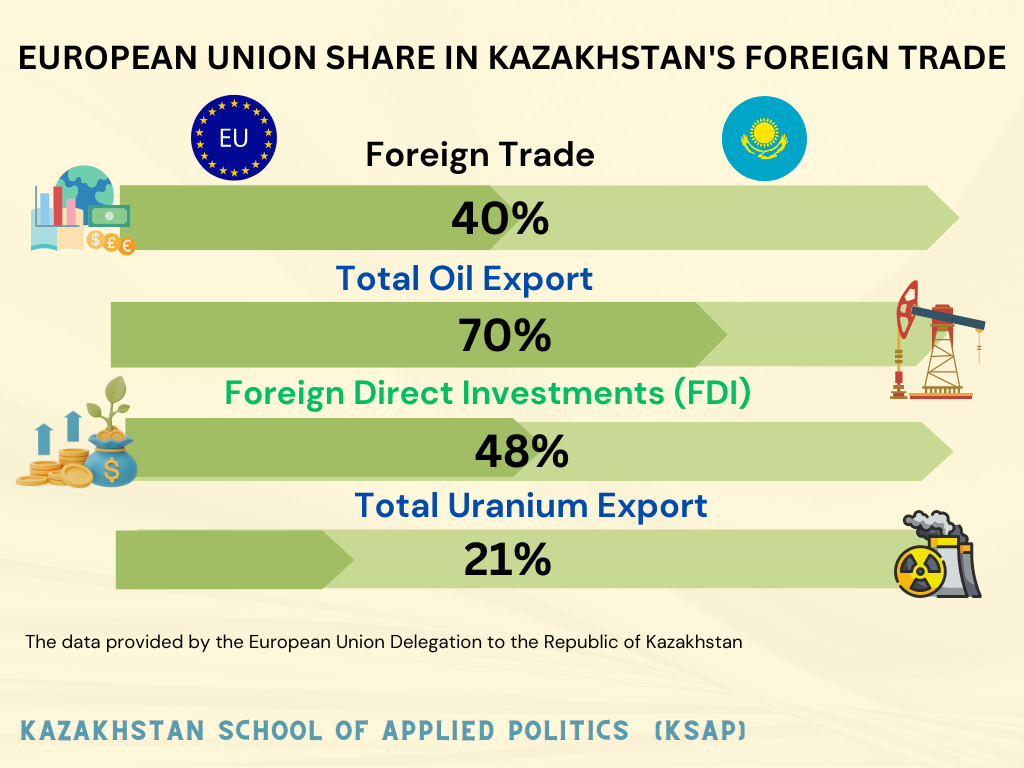

Such significant blows to oil infrastructure could also damage the export of Kazakhstani oil. The main portion of Kazakhstan’s oil exports (around 70 percent) are sent through the Yuzhnaya Ozereevka terminal near Novorossiysk to European Union countries. The EU currently serves as the primary and most important trade and economic partner for Kazakhstan. The EU accounts for 40 percent of the country’s external trade and 48 percent of total foreign direct investment (FDI) inflow.

Furthermore, Kazakhstan supplies 70 percent of its exported oil to EU countries and ranks third among non-OPEC members in terms of raw material supplies to the European Union. The share of Kazakhstani oil makes up about 6 percent of total EU oil imports. Kazakhstan also provides 21 percent of the uranium imported into the EU.

Considering that oil is the primary export commodity ensuring the inflow of foreign currency for Kazakhstan, trade with the European Union is a crucial element in the architecture of the country’s economic stability and security.

Concerns about the unreliability of transportation and transit routes through Russian territory, through which the export of Kazakhstani products occurs, predate Russia’s attack on Ukraine. Unfortunately, Kazakhstan’s problems with exports to Russia and transit through Russia have been chronic.

Russia regularly, in violation of the rules governing the Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU), unilaterally restricts the access of Kazakhstani products to its domestic market, applying non-tariff regulatory methods, including unjustified decisions by regulatory government organizations (Rospotrebnadzor, Rosselkhoznadzor). Additionally, Kazakhstani goods transiting through Russian territory to external markets face systematic problems (such as Russia’s imposition of a quota on the export of Kazakhstani coal through its territory in 2019), often driven by political motives. These disruptions regularly result in multimillion-dollar costs for Kazakhstan’s economy.

At present, the situation has been significantly aggravated by economic sanctions imposed by the West against Russia and Belarus. This has ultimately undermined the long-term, relative stability of the already problematic “Northern Trade Route” for Kazakhstan. For many years, while enjoying economic comfort and aligning their path with Russian interests, the political elite of Kazakhstan often neglected serious steps toward diversifying export routes. As a result, the authorities effectively pushed the country into a “transit trap” set by the Kremlin, which had a negative impact on the country’s economic development and heightened Kazakhstan’s economic and, consequently, political dependence on Russia.

Now the Trans-Caspian International Transport Route (TITR) project, passing through Azerbaijan and Georgia, is gaining new momentum. Kazakhstan’s President Kassym-Jomart Tokayev, at the summit of the Council of Cooperation of Arab States of the Persian Gulf (CCASG) and Central Asian countries held on July 19, 2023, in Saudi Arabia, announced plans to increase cargo transportation along the TITR to 500,000 containers per year by 2030. In comparison to the Northern Corridor, the TITR (the so-called Middle Corridor) offers a more economical and faster trade route, reducing the distance by 2,000 kilometers. Additionally, it benefits from favorable climatic and political conditions. Good neighborly and partnership relations with Azerbaijan and Georgia (through which the Trans-Caspian route passes), as well as the political predictability of these countries, can ensure more favorable transit conditions for Kazakhstan.

The development of the TITR and other alternative transport routes will be a significant step in ensuring economic security. This is part of a natural response to ongoing problems with transporting goods through Russia. The benefits of the development of the TITR should be shared by all the countries along its route. Among the main advantages that the participating countries will gain from the project, the following can be highlighted: Transit fees and additional revenues; creation of necessary economic infrastructure to facilitate unhindered transit, including pipelines, railways, ports, and terminals; increased geopolitical influence through control over key transit routes; and stimulating the development of the energy sector through the passage of oil through specific territories.

For Kazakhstan, in particular, the development of the TITR offers broader access to global markets for selling oil and other goods and accelerated transportation through the use of Azerbaijan’s developed infrastructure for oil delivery and processing, ensuring more efficient supply management. The route also diversifies risk: With multiple routes in place, Kazakhstan can reduce the likelihood of problems or delays in transit.

An important outcome of this project could be closer cooperation between Kazakhstan and Azerbaijan, which would have a positive impact on various aspects of interaction. This could range from joint investments in infrastructure and exchange of experience and technologies, to strategic strengthening of political, economic, and cultural ties between the two countries.

Unfortunately, but for quite predictable reasons, the TITR project faces strong opposition from Russia. Recently, Russian media employed a set of political technology clichés, describing the situation as a “game in the dark.” (One headline, for example, read: “A Game in the Dark: Kazakhstan is Building a Transport Corridor around Russia”). This is not surprising, considering that successful completion of the project would strip the Kremlin of an important leverage point over Astana.

The significant economic effects that Kazakhstan would benefit from in developing the TITR would not favor the Kremlin, which is accustomed to “twisting the arms” of economically vulnerable neighbors.

It’s also worth noting that the project comes with its challenges. Among the major obstacles are the complex logistics of the route and high investment costs for rolling stock and infrastructure. The logistical complexities involve double transshipment between rail/road and sea transportation through the Caspian and Black Seas. Currently, cargo transportation across the Caspian is primarily carried out by Azerbaijani vessels. To achieve the declared capacity, substantial investments are needed in transportation infrastructure and the expansion of the maritime trading fleet. Additionally, customs inspection times need to be reduced.

The realization of the TITR project will require not only financing but also strong political and diplomatic will, as well as competent project management from the governments involved.