The re-invasion of Ukraine by Russia in 2022 is proving to be a key testing ground for modern theories of war and cybersecurity. Analysts with a focus on the Asia-Pacific region should pay careful attention to the course of the conflict to extract critical lessons. Many expected a revolution in warfare aided by advanced artificial intelligence or cyber strikes. Instead, the war has demonstrated the importance of precision strikes, a Cold War era technology. The conflict has reverted to attritional trench warfare from the last millennia. This leaves current and future “edge” technologies that use cyberspace without a significant role in impacting the conflict.

As professional pundits bang the drums of cyber war, the failure to properly evaluate the role technology plays in modern conflict is telling. Observers miss critical advances in warfare, believing in the promise of new disruptive technologies. Even analysts from the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) have assessed that Russia executed a “cyber thunder run,” a quick burst in attacks that paved the way for conventional forces when the war began. To evaluate these expectations, beliefs, and assess a more accurate role of cyber competition, our research team quantified attacks, targets, and methods.

In a recently released Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) report, we find that there is considerable evidence of an uptick in cyber conflict associated with the war, yet few significant cyber operations. Moreover, we witness little change by Russia in its targets or methods before and during the conflict. Analysts in the Asian region should focus on the critical investments that aid the defense in moderating the impact of technology on the battlefield. It will be important to redirect best practices to increase resilience to limit the ability of emergent technologies to alter the dynamics of war.

Documenting Cyber Operations in Ukraine

Collecting data on cyber operations during the Russo-Ukrainian War is clearly possible. Fixating on early media reporting is a common mistake because such information is often incomplete. For our report, we leveraged public information on operations released by Ukraine and Microsoft to document ongoing attacks during the conflict.

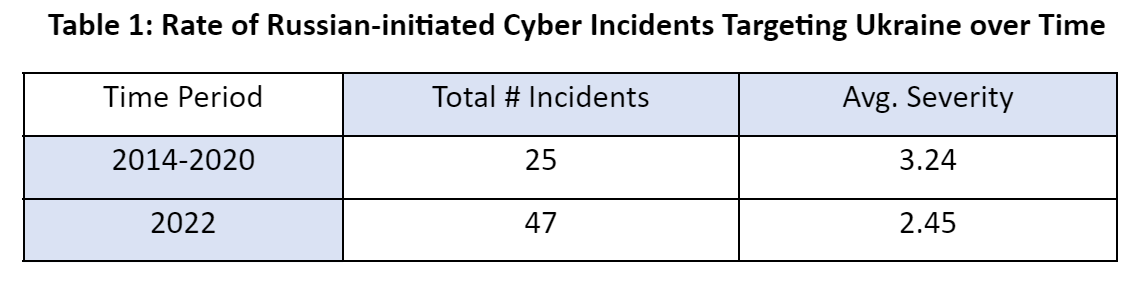

As Table 1 demonstrates, during the first months of the present-day Russo-Ukrainian war there were 47 cyber incidents with an average severity of 2.45 on a scale of 1 to 10 (with 0 indicating no cyber activity and 10 marking cyber incidents with the potential outcome of massive deaths). Overall, the severity declined when compared to the pre-war sample. During the 2014-2020 period, cyber operations were a useful tool in sowing confusion, avoiding attribution, and preventing escalation. However, when full scale conflict began these attributes became less salient and conventional weapons of destruction were the preferred military tactic.

Source: Cyber Operations during the Russo-Ukrainian War, From Strange Patterns to Alternative Futures

Since cyber operations ultimately represent a weak form of coercive diplomacy, these cheap signals fail to achieve sufficient leverage to compel a target. There has never been a concession, documented as a change in behavior in the target, during the cyber exchanges between Ukraine and Russia, both before and during the war. We also note that Russia didn’t even shift targets toward the Ukrainian military, instead continuing to focus on civilian targets.

Based on Microsoft’s reports on the war, we would also expect coordinated cyber actions with conventional operations – in the form of multidomain operations – should support, or complement, Russia’s overall efforts to dominate Ukrainian forces on the battlefield. Yet, our analysis shows that there are only seven instances (15 percent of the sample) of multidomain operations. Searching for an impact from cyber operations through severe events, concessions, or coordinated multidomain action, we find very little evidence for each expectation, demonstrating that the cyber lessons from this war are confounding to conventional narratives.

Implications for Asia-Pacific Region

There is little clear demonstrable impact on the course of the war enabled by cyber operations. Those with a role in the conflict recognize this reality, with a representative of the U.S. Department of Defense noting, “I think we were expecting much more significant impacts than what we saw… it’s safe to say that Russian cyber forces as well as their traditional military forces underperformed expectations.”

While it is difficult to draw large conclusions from one example, crucial cases often animate discussions and shape future operations in different geopolitical situations. The outcome of cyber conflict in Ukraine was more restrained than most thought likely, with defense and collaboration with partners playing a critical role while an volunteer army of hackers gave up rather quickly.

This suggests that regular cyber forces will be critical in any forthcoming conflict in the Asia-Pacific region. No state can depend on volunteer armies of citizen hackers. More importantly, states in the region that are pressed by Chinese-directed cyber operations need to collaborate with security partners and the private sector to enable the defense in the future.

Our findings cement the historic inability of cybersecurity to be a coercive force in warfare. What this means for war in Asia, or the defense of Taiwan, will be a critical task for regional strategists to sort out. There appears to be a clear case for influence operations as tools to shape public opinion, but there is little evidence that cyber operations can serve as a magic bullet to enable China’s vision of reclaiming lost territory.

Lessons for the Future

Expect China to learn from Ukraine’s success and seek to prepare the environment for a conflict of their choosing. While cyber operations will continue to be useful tools of repression, there is little that these hybrid tools can do on the battlefield to aid a conventional invasion.

According to our CSIS report, we envision two key future paths in the Asian region. Continued cyber stalemate with foiled cyber offensive operations peppering the landscape is likely. China will continue to invest in domestic surveillance and intelligence collection, possibly learning from Russia’s failed efforts to integrate cyber operations with conventional war fighting capabilities.

The second path, and not mutually exclusive, suggests that the real utility of cyber operations might be to control the information environment both within China and globally during any potential conflict. Digital lies can help create an international backlash against any targeted nation and the United States, creating dissent at home and aboard. Propaganda tailored to the American Right during the Russo-Ukrainian War destabilized networks of support for a vulnerable Ukraine.

As we are witnessing during the war, with everything on the line for both Russia and Ukraine — national survival, the stability of leadership, and the status of the global international order — Russia failed to leverage cyber actions in support of combat operations. It is unlikely that China will fail in the same ways, but it’s also becoming more evident that waging cyber conflict for coercive intent is currently a bridge too far as long as vulnerable states take defense seriously.