Our popular memory of World War II in the Asia-Pacific theater focuses almost entirely upon the maritime dimensions of this titanic struggle between the Allies and Japan. This simple narrative holds that the U.S. Army fought the war in Europe while the U.S. Navy dealt with Japan in a waterborne and aerial struggle, and the U.S. Marines did the ground fighting, seizing a series of key islands as stepping stones on the road to Japan.

The vast majority of books about the war have focused on the naval dimensions or on famous Marine-dominated battles such as Iwo Jima and Tarawa. Wikipedia’s extensive Pacific War entry mentions the U.S. Army only a few times and with no actual source citations. HBO’s excellent, gritty miniseries “The Pacific” largely ignored the Army’s role to tell the story of the war through the experiences of three Marines: John Basilone, Robert Leckie, and Eugene Sledge. The series thus reinforced the notion that the Marine Corps did the ground fighting against Japan.

But the reality is that the Army fought the vast majority of the ground war — and did the bulk of the fighting overall — and it did the plurality of the dying to win victory over Japan. The Marine Corps made 15 amphibious combat landings over the course of the entire war. In the spring of 1945, Lieutenant General Robert Eichelberger’s Eighth Army alone carried out 35 amphibious landings over just a five-week period in the Philippines. At full strength, and at its largest size ever, the Marine Corps mobilized six combat divisions, comprising about a quarter million troops in theater, all of whom were fully dependent on the Navy and the Army for logistical support, since the Corps was designed to function as an expeditionary fighting force, not a self-sustaining military organization. By contrast, the Army deployed 31 infantry and airborne divisions, plus several more regimental combat teams and tank battalions whose manpower equated to three or four more divisions. In addition, the Army handled enormous logistical, transportation, intelligence, medical, and engineering responsibilities.

I should hasten to add that my intention is not to denigrate the Marine Corps. Quite the contrary. The Marines comprised only 5 percent of the U.S. armed forces in World War II, and yet Marines suffered 10 percent of all American battle casualties, including over 19,000 fatalities. From Guadalcanal to Okinawa, Marines played a key role in a plethora of crucial victories and more than earned the service’s vaunted reputation for valor, a fact that most any soldier who fought alongside the Marines readily recognized. But, as those percentages indicate, Marines were few in number, and the war in the Asia-Pacific was vast, requiring large ground forces in a supposedly maritime theater.

To wit, by the summer of 1945, 1,804,408 Army ground soldiers were serving somewhere in the Pacific or Asia. They were part of the third largest land force ever fielded in American history, behind only the European theater armies in World Wars I and II. And yet, in our popular memory, the Army in the Pacific remains, for such an enormous force, surprisingly anonymous. A staggering 111,606 Americans were killed or went missing in the war against Japan. The greatest plurality of these deaths, 41,592, occurred among Army ground soldiers. So indisputably, the Army, by design, did most of the planning, the supplying, the transporting, the engineering, the fighting, and the dying to win World War II in the Asia-Pacific.

Why is it so important 80 years later, in the 21st century, to understand these historical facts?

Certainly not for narrow reasons of parochial service pride or counterproductive interservice rivalry. Any rational person understands the fundamental importance of sea power and air power, whether in 1945, 2025, or beyond. Even so, if we mistakenly believe that the war against Japan was largely a maritime struggle involving only expeditionary ground forces, then we are highly likely to misunderstand the nature of any future conflict in the Indo-Pacific region. If Army ground forces played an outsized role from 1941-1945, then there is a likelihood that this will happen again. Contrary to the old yarn, history does not necessarily always repeat itself. But it does demonstrate patterns.

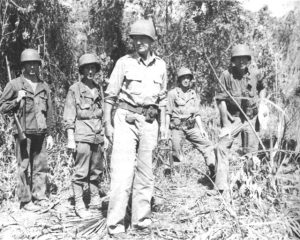

The unglamorous locales of the Pacific War, from the jungles of New Guinea, Guadalcanal, and Mindanao to the frozen valleys of Attu, the rocky caves of Biak and Peleliu, the ruined metropolitan blocks of Manila and Cebu City, the grassy hills of Guam, and the mind-numbing ridges and peaks of Myanmar, carried with them a troubling whiff of clairvoyance.

“This is the Pacific, WWII, all over again,” Stanley “Swede” Larsen, who served in World War II with the 25th Infantry Division, wrote from Vietnam in 1965 to one of his former World War II commanders. Now a general, Larsen saw “the same shortages, same malaria problems, personnel headaches, transportation bottlenecks etc. Little… could I have guessed exactly 20 years ago that we would go full circle and be back at the same game, in the same part of the world.”

Indeed, as Larsen indicated, the battlegrounds of the Pacific, and the war itself, hinted strongly at the patterns of succeeding history, especially for the Army, which, as an institution, shaped so much of that history. In my 2010 book “Grunts: Inside the American Infantry Combat Experience, World War II Through Iraq,” I demonstrated that, during a time of enormous advances in aerial, seaborne, nuclear, communications, and space age technology — the existence of which was supposed to make ground fighting obsolete — instead the opposite occurred.

Wars were largely decided on the ground and, correspondingly, that’s where the casualties occurred. From Korea to Afghanistan, over 90 percent of American wartime casualties have been suffered by ground troops, most of whom were Army soldiers killed, wounded, or captured somewhere on the Asian land mass. Subsequent conflicts in Syria, east Africa, and especially Ukraine have only demonstrated even more this tendency for the ground as the arena of decision, even in modern warfare. It doesn’t take special insight or expertise to understand this, just a basic familiarity with the relevant history.

I truly hope that Army leaders, and defense policy decision makers as a whole, will study the Army’s World War II experience in the Asia-Pacific theater to arrive at the obvious conclusion that a future war in this part of the globe is highly likely to involve substantial ground forces that will play a key role in deciding the outcome of the conflict. In practice, this means the Army must once again take the lead in fighting, and logistically supporting, such a war.

The Indo-Pacific is not exclusively a maritime theater. If World War II teaches us anything, it is that navies, armies, and air forces are intertwined, best functioning as coordinated forces, but that ultimate victory usually depends on the control of key ground, with the corresponding bounty of resources, sustenance, and populations. In short, land forces matter greatly, even in areas dominated by oceans.