The Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) has stiffened its stance toward its conflict-torn problem member Myanmar, with chair Indonesia openly acknowledging the lack of progress in implementing the bloc’s peace plan.

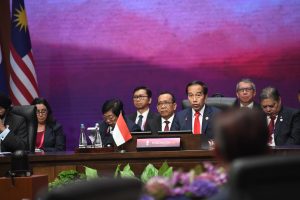

In a statement issued yesterday following its annual summit in Jakarta, Southeast Asian leaders “strongly condemned” the continuing violence in Myanmar, and for the first time directly blamed the Myanmar military for the upsurge in conflict that has engulfed the country since its takeover in February 2021.

The statement said that leaders “strongly condemned the continued acts of violence in Myanmar” and were “gravely concerned by the lack of substantial progress” on the implementation of the bloc’s Five-Point Consensus. Agreed in April 2021, the Consensus called, among other things, for an immediate cessation of violence and inclusive political dialogue aimed at the resolution of the conflict.

Most significantly, the leaders used the statement to “urge the Myanmar Armed Forces in particular, and all related parties concerned in Myanmar to de-escalate violence and stop targeted attacks on civilians, houses and public facilities, such as schools, hospitals, markets, churches, and monasteries.”

The singling out of the Myanmar military was a first for the 10-nation bloc, which has come under fire for failing to take a harder line against the Myanmar junta, which despite agreeing to the Five-Point Consensus, has repeatedly violated both its spirit and letter. As Indonesia’s Foreign Minister Retno Marsudi told reporters, there has been “no significant progress” in the implementation of the Consensus.

The statement, officially titled the “ASEAN Leaders’ Review and Decision on the Implementation of the Five-Point Consensus,” contained a number of other small but significant steps forward in the bloc’s response to the situation in Myanmar. The first was to set up an “informal consultation mechanism” – an ASEAN “troika,” as it is already being called – comprising the current, past, and future ASEAN chairs. The aim of this is to ensure a degree of continuity in the bloc’s response to Myanmar from year to year.

The statement also confirmed that Myanmar will be stripped of its next chairmanship of the bloc in 2026, presumably to avoid the damaging Western diplomatic boycott that might result from junta-hosted summits. Instead, the 2026 chairmanship “shall be assumed by the Philippines and, subsequently, the Chairmanship rotation continue based on alphabetical order, until a different decision is made.”

It has already been reported that Myanmar would relinquish the 2026 chairmanship – I wrote on the subject last month – but the statement clarified a couple of points. First, while initial reports suggested that Myanmar would put off chairmanship for a year and take up the helm in 2027, it is now clear that it will now have to wait until the next 10-year “cycle” before chairing the organization again.

Moreover, as Aaron Connelly of the International Institute for Strategic Studies noted in a useful thread on X, formerly known as Twitter, this situation differs from the 2006 suspension. In that instance, “the SPDC junta at the time was allowed given the chance to save face by ‘giving up’ the chair,” Connelly wrote. “But this document makes clear in unusually stark language that, this time, it was the decision of the other nine leaders.”

The statement also reaffirmed the decision made at the corresponding summit in 2021 that representatives of the military junta will be barred from high-level ASEAN meetings, pending “concrete progress in the implementation” of the Five-Point Consensus.

A spokesperson for the opposition National Unity Government (NUG) told Leong Wai Kit of Channel News Asia that the decision to withdraw the 2026 chairmanship was “a big blow” to the junta. The spokesperson also called on ASEAN to “take further punitive steps against the junta,” such as barring all junta representatives from all ASEAN-related meetings.”

While the ASEAN leaders did not perhaps go as far as some would have liked – the bloc said that it would retain the much-maligned Five-Point Consensus as its “main reference” for addressing the Myanmar crisis – the bloc at least succeeded in sending the junta a message that it cannot dictate terms to the ASEAN Chair.

In his thread on X, Connelly cited sources to the effect that the document, which required consensus among the “ASEAN 9,” “did not require difficult negotiations.”

“Member states are more united on Myanmar than the popular narrative would suggest, particularly following this week’s change of government in Thailand,” he said.

Whether this will make much of an impression on Naypyidaw remains to be seen. Unsurprisingly, the junta’s foreign ministry said in a statement that it “rejects” the ASEAN statement, accusing the nine other members of breaching the bloc’s norm of non-interference in the affairs of member states.

“Although the ASEAN Chair consulted Myanmar on the draft document, the views and voices of Myanmar are not taken into account,” it stated, adding that the document was “not objective and decisions are bias [sic] and one-sided.”

Perhaps not coincidentally, on the eve of the ASEAN meetings, the military administration hosted officials from China, India, and Thailand, to discuss various aspects of bilateral cooperation. This signals its intention to ignore ASEAN’s admonitions, consolidate its control, and focus on building ties with neighboring countries and others, like Russia, that are willing to work closely with it.

There is probably little that ASEAN can do to coerce the Myanmar military within the bounds of its consensus-based decision-making norms. However, if it cannot make serious headway in resolving the crisis in Myanmar, it can at least move to limit the damage to the bloc’s international standing.