Zambia’s President Hakainde Hichilema has just returned home from almost a week in China, during September 10-16. Prior to the visit, journalists speculated that debt resolution must be the main priority for the visit, but that reflects a very shallow understanding of the dynamics in China-Zambia (and indeed China-Africa) relations.

Hichilema is the fifth African head of state to visit a post-pandemic China, following top leaders from Tanzania, Algeria, Eritrea, and Benin. In the past, research by Development Reimagined has found a long-term positive correlation between visits from African leaders to China and more Chinese investment and cooperation. Such visits are when deals are cemented. Zambia ranks among the most active African countries when it comes to Chinese engagement, with nine visits to China of its leaders since 2003, matching well with its rank as the third largest destination for Chinese foreign direct investment (FDI) on the continent.

This trend is not new. China and Zambia cooperated during anti-colonial struggles, and close diplomatic ties were established soon after independence in 1964. The iconic Tanzania-Zambia Railway (TAZARA) was raised by Zambia’s founding President Kenneth Kaunda with China’s first-generation leaders during his first visit in 1967. By connecting Zambia’s Copperbelt province to the seaport of Dar es Salaam, the so-called “liberation project” had a strong economic objective that the multilateral and other bilateral financial organizations found it hard to recognize and justify at the time: it materially reduced Zambia’s dependence on still colonized Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe) and apartheid South Africa.

China stepped in to provide funding instead. The railway thus came to symbolize Chinese support for Pan-Africanism and was the starting point of extensive infrastructural support that has since characterized China’s development cooperation with Africa more broadly.

The last in-person meeting between the presidents of Zambia and China took place during the 2018 Forum on China-Africa Cooperation (FOCAC) Summit in Beijing. It was a sensitive time, when the notion of “debt trap diplomacy” had just surfaced, and Zambia was depicted as a major victim. Although Zambia’s then-President Edgar Lungu had hit back hard against those accusations, such narratives continued to plague the relationship, despite China and Zambia being “all-weather friends.” (Incidentally, this frequently-used term in Chinese diplomacy was first coined by Kaunda).

The COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated the debt issue. In 2020, Zambia became the first African country to default on debt when it failed to make a Eurobond payment. Zambia then became the first country to apply to the G-20 Common Framework, an initiative designed to coordinate debt-restructuring efforts by both traditional and emerging lenders. Doing so enabled Eurobond holders to get their payments from the International Monetary Fund (IMF) via arrears, which Zambia will have to pay back to the IMF at some point. However, internationally the blame for Zambia’s challenges in debt resolution thereafter was pinned on China – although not it’s worth noting that the Zambian government itself has never expressed this view.

At the time, 30 percent of Zambia’s total loans were owed to China, but these were mostly concessional loans, channeled through policy banks like the China Exim Bank. In 2020, the year of Zambia’s default, Zambia paid $436 million in interest on external debt stock, with China accounting only for 5.3 percent of this (a ratio that dropped to just 2.1 percent in 2021). Historically, China had also provided debt relief to Zambia on request multiple times – in total worth $259 million since 2000, which tops all sovereign creditors.

Hence, amid the debt crisis Hichilema has been pragmatically avoiding picking one side as a tactic to press the other for compromise. He made efforts to refute the stigmatization of China’s role in the multilateral settlement to mitigate the mistrust among the different creditors.

Nevertheless, facing an impasse after almost two years, and with China finally opening up post-pandemic, Zambian Treasury and Central Bank officials traveled to China prior to the 2023 IMF and World Bank spring meetings. Their proposals that paved the way for a breakthrough deal for all bilateral creditors to extend repayment of $6.3 billion in loans to 20 years with a three-year grace period. (It should be noted that no progress has been made so far on engaging private lenders and multilaterals in Zambia’s debt relief, despite the protracted negotiations.)

So, if Hichilema’s week-long trip to China was not about debt, what was it about?

The answer is growth.

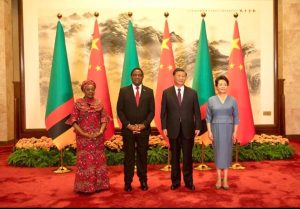

With the 60th anniversary of their diplomatic relations and the next FOCAC Summit coming up in 2024, Hichilema’s visit led to an upgrading of China-Zambia bilateral ties to a “comprehensive strategic and cooperative partnership,” the highest classification so far applied to China’s partners on the African continent. The joint communique pointed to synergies between Zambia’s Eighth National Development Plan and the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), critical for China’s international reputation. This all indicated a determination from Hichilema and Chinese leader Xi Jinping to flip over to the next page to discuss long-term development and economic growth – not debt.

A particular highlight of the visit was China’s commitment to support Zambia’s ambition to transform into an industrial hub, capitalizing on its resource endowments. According to the China-Africa and Trade Relations Report 2023, China’s imports from Africa are dominated by mineral imports, which accounted for 57 percent ($67.09 billion) of total imports in 2022, with Zambia being the second largest source. This means Zambia is one of the few African countries that has a positive trade balance with China. However, the Zambian government wants to diversify the trade pattern, especially in value-addition and manufacturing.

Before he arrived in Beijing, Hichilema’s six-day visit started in Shenzhen, China’s tech hub. There, Hichilema invited tech giants including Huawei, ZTE, Tencent, and BYD to leverage Zambia’s resources for key component production. MoUs were signed with ZTE for a smartphone assembly plant and with Huawei to improve ICT infrastructure.

During Hichilema’s trip to Jiangxi Province, the Zambia Development Agency attained two investment commitments: Pingxiang Huaxu Technology will build a wind and solar hybrid power generation project worth $800 million, and Jiangxi Special Electric Motor Company will invest $290 million for a lithium battery manufacturing plant in Zambia’s Southern Province.

This all makes strong economic sense. Copper resources, existing processing bases, and a clean energy-driven electricity system make Zambia highly competitive in producing renewable energy components and systems within the continent. Earlier this year, during his attendance at the Mining Indaba in Cape Town, South Africa, Hichilema provided regulatory clarity (such as on taxation) to get the sector back on track from resource nationalism. He also underlined a strong will to work with foreign investors to tap the country’s potential in the critical minerals for green transition. These deals made during the China trip are concrete steps that can turn the government’s vision into reality.

Hichilema was also able to extract commitment from China to finance old and new large infrastructure projects – despite continued international speculation that China is no longer lending in this way. The TAZARA Railway network is expected to be rehabilitated in the first quarter of 2024. New projects – including the Ndola-Lusaka dual carriageway (which was halted earlier due to a loan cancellation as part of Zambia’s debt management), the Lusaka-Livingstone-Kazungula bridge highway, and the Kabwe solar photovoltaic power plant – are all on the horizon as well.

Last but not least, Hichilema also secured commitments from China to import more agricultural products from Zambia, such as blueberries, building on a soybean export agreement made in 2022, while boosting investment in agro-processing, fertilizers, pesticides, and agricultural machinery.

These deals all support key Zambian priorities: job creation, reduced reliance on imports, and the aim of increasing Zambia’s potential to export either to China or to neighboring countries. The goal is to bolster Zambia’s growth, increasing incomes and strengthening the country’s financial sustainability in the long term. And of course, China sees an interest in doing so, not only to ensure that Zambia’s future loans are repaid, but also to diversify its own sources of economic growth and supply chains.

These agreements are as important for the two countries as debt relief itself, if not more. They create a stronger path for debt sustainability.

So what does this mean for other African countries, especially those facing debt payment challenges, but who also still want to generate post-pandemic growth?

Zambia’s lesson in engagement with China at least is simple: if you don’t ask, you don’t receive.

Zambia actively pursued both bilateral and multilateral debt resolution, and in the end it was – contrary to reports by others – not IMF advocacy but Zambia’s own initiative that paved the way for a deal. And Hichilema’s visit to China has demonstrated that Zambia is now taking the initiative to use debt and other resources to set a new growth path that emphasizes building up its production capacity.

Other African leaders visiting China can do the same. Approaching the 10th anniversary of the BRI, China is also seeking to build a reputation as a provider of public goods and supporter of practical development to partners on the continent. As Zambia did, African countries should leave negotiations on debt relief and terms to their finance ministers and central bank governors, and instead prepare a pragmatic yet ambitious agenda – including pitches for new investment, new loans for infrastructure, and new trade – and showcase their strategic importance. That is the real prize.