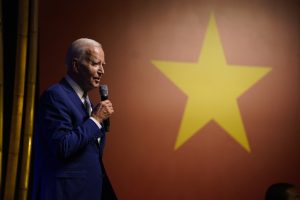

This weekend, for the first time, a U.S. president paid a state visit to Vietnam on the invitation of a general secretary of the Communist Party of Vietnam (CPV). On the occasion, President Joe Biden and General Secretary Nguyen Phu Trong announced the upgrade of the bilateral relationship from a comprehensive partnership to a “Comprehensive Strategic Partnership for Peace, Cooperation and Sustainable Development.” The upgrade, which Biden mentioned in July, has put the United States on par with China and Russia in Vietnam’s diplomatic hierarchy.

Indeed, the full text of the Biden-Trong communique released by the CPV Central Committee’s Commission for External Relations puts much emphasis Vietnam-U.S. shared interests. Trong noted that Vietnam and the United States fought on the same side against fascism during World War II and that President Ho Chi Minh quoted a portion of the U.S. Declaration of Independence in the introduction of the Vietnamese Declaration of Independence after defeating fascism, signaling that Vietnam and the United States can overcome ideological differences to cooperate against a common enemy. Importantly, like the 16-word guideline of the Vietnam-China Comprehensive Strategic Partnership, the Vietnam-United States Comprehensive Strategic Partnership now also has its own 16 words:

Gác lại quá khứ (Closing the past)

Vượt qua khác biệt (Overcoming the differences)

Phát huy tương đồng (Strengthening the similarities)

Hướng tới tương lai (Looking to the future)

Remarkably, while the U.S.-Vietnam Comprehensive Partnership was signed in 2013 by former President Barack Obama and his Vietnamese counterpart President Truong Tan Sang, the fact that Biden signed the agreement with Trong, the head of the CPV, is the strongest signal that the U.S. can send that it respects Vietnam’s political system and the role of the CPV under Trong’s leadership indefinitely. It is quite clear that the United States and Vietnam are sending signals to one another that ideological differences will not hinder the partnership and Vietnam acknowledges that the United States respects Vietnam’s internal security. The United States benefits from a politically stable autocratic Vietnam, and Hanoi should not fear color revolutions or U.S. interference into its domestic affairs. After all, the United States supports a “strong, independent, resilient, prosperous Vietnam,” not a democratic one.

The U.S.-Vietnam partnership is mostly intended to check China’s aggressive behaviors at sea. As such, China’s policy towards the U.S.-Vietnam partnership has been to emphasize the ideological differences between Hanoi and Washington and the untrustworthiness and drawbacks of an extra-regional great power’s security commitment to Hanoi, in order to drive a wedge into U.S.-Vietnam security cooperation. The United States and Vietnam have done their best to solve the first part of the Chinese wedge strategies by continuously cultivating political trust, so now after the relationship upgrade, the next step is to solve the second part to add more substance to the new partnership. In other words, beyond overcoming the ideological differences in their bilateral relationship, Hanoi and Washington need to be on the same page on how to respond to Chinese bullying.

Although Vietnam wants to expand the scope of defense relations with the United States, it must be aware of potential Chinese retaliations. Throughout the negotiations for the upgrade, the United States was a more eager party than Vietnam. With the upgrade, there will be more expectation from the United States to enlist Vietnam into an anti-China coalition under a “collective security” framework. This is understandable considering the U.S. perceives China to be its most serious competitor, while Vietnam wants to maintain good relations with China to avoid having to fight an unnecessary war with its northern neighbor.

Such a difference puts Vietnam in a tricky situation: Vietnam welcomes more U.S. support, but it cannot ask for too much, despite the U.S. willingness to give more, in the absence of major aggression from China. This explains why before Biden’s visit, Trong visited the China-Vietnam Friendship Pass with Chinese ambassador to Vietnam Xiong Bo and met the Chinese Communist Party international department head Liu Jianchao to enhance Vietnam-China “political trust.” China’s continuing use of “gray-zone tactics” in disputed waters in the South China Sea will further caution Vietnam against seeking more security assistance from the United States, in order to avoid a spiral toward conflict.

What this entails is that while the United States has taken the first step of declaring its respect for Vietnam’s political system, Vietnam should take the initiative to determine how far it wants its defense cooperation with the United States to go. This is to ensure that the United States is aware of the appropriate amount of security support that Vietnam needs to avoid offering more than necessary and angering China in the process. Vietnam’s strategic thinking from the Third Indochina War suggests that Hanoi will only join the U.S. side if and only if it deems its relations with China cannot be fixed by diplomatic means and continued deference to China cannot satisfy Vietnam’s security interests.

At the moment, there are few indicators that Vietnam and China are on the verge of a total diplomatic breakdown, as was the case in the run up to the signing of the Soviet Union-Vietnam alliance treaty in 1978. And even in that case, it was Hanoi that determined the level of security cooperation with Moscow despite the Soviet eagerness for Vietnam to join its anti-China coalition shortly after the Vietnam War ended. In short, the next step for the U.S.-Vietnam partnership is to assess realistically how much security assistance Vietnam needs from the United States and when Vietnam should receive such assistance. The United States needs to be patient if Vietnam says no to any of its security initiatives, just like Vietnam did to those of the Soviet Union.

Vietnam may have equated the United States with China in its diplomatic hierarchy, but that does not mean that it will side with the United States against China. From Hanoi’s perspective, the comprehensive strategic partnership should contribute to regional peace, not regional instability, and that means not provoking China unnecessarily. Not only did Hanoi try to dilute the significance of the U.S.-Vietnam partnership upgrade by offering comprehensive strategic partnerships to other countries like Singapore, Indonesia, and Australia; it also emphasized in the title of the U.S.-Vietnam Comprehensive Strategic Partnership that this is a partnership for peace and economic development. Hanoi and Washington have solved the first part of the Chinese wedge strategies. The key to further developments in their bilateral relations is how to solve the second part without creating an unnecessary conflict with Beijing.