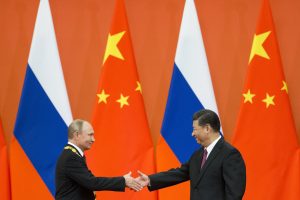

In early February 2022, several weeks before Russia launched its invasion of Ukraine, Russian President Vladimir Putin traveled to Beijing. where he signed a joint statement with Chinese President Xi Jinping that announced that there were “no limits” and “no forbidden areas of cooperation” between the two states. These references, however, were omitted in the March 2023 joint statement released after Xi’s return visit to Moscow.

In short, the course of the war has revealed the limits to the “no limits” relationship, exposing the tensions between Russia and China. China has reservations about Russia’s conduct and performance in waging the war, as well as its larger international impact. At the same time, China and Russia remain fundamentally united in their joint negative appraisal of the neoliberal international order, characterized by the hegemonic dominance of the West and the United States in particular. Although China has adopted a formal position of neutrality, and has mostly adhered to the Western sanctions against Russia, it has largely appropriated the Russian narrative on the conflict, describing it as a proxy war between the West and Russia in which Russian actions are framed as a legitimate response to an existential threat.

Nonetheless, over time, indications have accumulated attesting to Chinese unease over the war. After meeting with Xi on the sidelines of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization conference in Uzbekistan in September 2022, Putin acknowledged that China had “questions and concerns” about Russia’s war in Ukraine. A few months later, Putin acknowledged in comments to the Valdai Discussion Club that he did not warn China before the Russian offensive, thus dispelling some of the speculation as to the extent to which the Chinese leadership was aware of the Kremlin’s intentions.

The Chinese leadership has become particularly alarmed over the saber-rattling propensity of Russian political elites to threaten the use of nuclear weapons. According to the Financial Times, Xi personally warned Putin against launching a nuclear attack on Ukraine during his March 2023 trip to Moscow. The Chinese side, however, does not seem to have been completely successful in reining Russia in. Putin, for example, announced the Russian plan to store tactical warheads in Belarus just four days after the signing of the 2023 joint statement in which the two states pledged not to stockpile tactical nuclear weapons beyond their borders.

Chinese official commentary about Russia’s military performance in Ukraine has been highly muted but it is certain that the Chinese leadership has been both shocked and dismayed by the inadequacies of the Russian military. Chinese social media has taken to labeling Russia a “weak goose” (菜鹅, cai’e), a play on words that refers to Russia as a weak state (in Mandarin, 鹅, meaning goose, is a homophone for 俄, shorthand for Russia). Zhou Bo, a retired senior colonel in the People’s Liberation Army, acknowledged in an October 2022 op-ed in the Financial Times that “Russia’s military image and credibility have crumbled.”

The Chinese leadership adopted a restrained non-judgmental response to the June 2023 events in which Evgeniy Prigozhin, the leader of the semi-independent mercenary Wagner Group, launched an unsanctioned march toward Moscow, labeling it an internal affair of the Russian Federation. Nonetheless, the affair and its aftermath, which has included the death of Prigozhin in a plane crash on August 23, the detention of Sergei Surovikin, the former top commander in Ukraine, and the purge of other military officers, no doubt conjures up some of the Chinese leadership’s worst fears about civil-military relations and the potential for regime instability in Russia.

The repercussions of the Russian invasion of Ukraine have percolated throughout the international system with a number of consequent effects, many of which are perceived as detrimental in the view of the Chinese leadership. It is by no means clear that China, as some have asserted, has emerged as a “winner” in the aftermath of the invasion. It is difficult to overestimate the importance of stability to China’s leaders, which is seen as a necessary precondition for the implementation of its economic and political goals.

In the geopolitical realm, hopes that the United States would be too preoccupied with Europe to focus on Chinese activity in the Asia-Pacific Region, especially with regard to Taiwan, have not been realized. China similarly did not anticipate the extent to which the United States and Europe would come together in joint opposition to the Russian invasion, and has been frustrated in its attempt to improve its relations with Europe, as well as to drive a wedge between the United States and Europe. Although China has benefited from the spectacular growth in trade ties between Russia and China as well as highly advantageous energy prices as a result of the Western sanctions, the fact remains that China’s economic relations with Europe and the United States are far more important.

The course of the war has also been an impediment to China’s political goal to construct a “Community with a Shared Future for Mankind” as an alternative to the Western dominated neoliberal order. Although many of the states of the Global South have chosen to avoid taking sides in the Russia-Ukraine conflict, Beijing’s strong verbal support for Russia has nonetheless had a negative impact on China’s soft power, and, in particular, the credibility of its constantly reiterated claims to uphold the norms of state sovereignty and non-interference in the internal affairs of other states.

As the war has ground on, China has become more involved in seeking a resolution of the conflict. On February 21, 2023, China published its Global Security Initiative Concept Paper, followed three days later (on the first anniversary of the onset of the invasion) by a 12-point peace plan, formally titled “China’s Position on the Political Settlement of the Ukrainian Crisis.” Both documents indicate the Xi leadership’s goal to enhance its role as a global actor in the realm of peacekeeping and security activities.

The Chinese peace plan is short on substance, providing no guide to the actual resolution of the conflict. It does, however, provide some insights into Chinese preoccupations with the war, including injunctions as to the necessity to keep nuclear power plants safe (point 7), and to refrain from any use of nuclear weapons (point 8). China’s specific concerns as to the economic impact (as well as to future economic possibilities) of the war are further visible in its commitment to facilitating grain exports (point 9), stopping unilateral sanctions (point 10), keeping industrial and supply chains stable (point 11), and promoting post-conflict reconstruction (point 12).

Although the Chinese peace plan was largely ignored as a serious endeavor, including initially by Russia, China has persisted in its diplomatic efforts. In April 2023, Xi had a one-hour telephone conversation with Ukrainian resident Volodymyr Zelenskyy, although the two presidents reportedly neglected to mention Russia as a topic of conversation. China further accepted an invitation to attend international talks based on a 10-point peace plan proposed by Ukraine (Russia was not invited) in Saudi Arabia last month, indicating its desire to participate in future discussions.

There are some hints that China, which is acutely sensitive to issues of territorial integrity and has failed to recognize the Russian occupation of Crimea, much less its declared annexation of the Ukrainian regions of Donetsk, Luhansk, Zaporizhzhia, and Kherson into the Russian Federation, is something less than a wholly enthusiastic supporter of Russian territorial ambitions in the war. In two interviews in the first half of 2023, one with the New York Times and the other with Al Jazeera, Fu Cong, the Chinese ambassador to the European Union, indicated that Beijing did not rule out support for Ukraine’s return to the 1991 borders that were established upon the demise of the Soviet Union, a geographical expanse that obviously includes Crimea.

The “questions and concerns” that Putin indicated that the Chinese leadership had raised six months into the war have not abated in the past year. Nonetheless, there are to date no substantive indications that China is rethinking its position as Russia’s closest partner, aside from Belarus and, arguably, North Korea. Just as an increasingly isolated Russia needs China, China sees close ties with Russia as a necessary bulwark and source of mutual support against a hostile West that is all too anxious to pursue a policy of divide and conquer, first vanquishing Russia and then going after China. In this scenario, the Chinese leadership faces an environment of constrained choices, in which it is imperative to prevent a situation in which Russia suffers a total defeat.

The Russian strategy, such as it is, appears to be to endure a stalemated conflict rooted in the not unrealistic hope that sooner or later Western actors will tire of providing support to Ukraine and press for a resolution of the conflict that the Kremlin can promote as a victory. The Chinese leadership, however, has its own agenda and a set of economic and political goals that are predicated on the restoration of a more stable and less contentious international environment.

The dynamics of the China-Russia relationship are highly opaque, but the Chinese foray into diplomacy suggests that Chinese and Russian visions of an acceptable outcome of the war are not wholly coincident. The question remains, however, as to China’s motivation (as well as its ability) to place pressure on Russia in coming to a negotiated settlement of the conflict. The next clues will emerge following Putin’s planned trip to China to attend the Belt and Road Forum next month.