A son of Indonesian President Joko “Jokowi” Widodo has been named as the head of a progressive political party, a step toward the creation of the political dynasty that many observers of Indonesian politics believe the leader is hoping to put in place before leaving office next year.

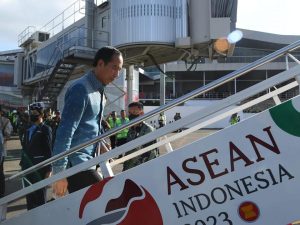

In a ceremony yesterday, Kaesang Pangarep, the youngest of Jokowi’s two sons, was named as the head of the youth-oriented Indonesian Solidarity Party (PSI), two days after he officially becoming a member of the party. In a speech, Kaesang paid tribute to his father, saying that he would “like to forge his path in politics for the good,” Reuters reported.

PSI was founded in 2014, and while it does not currently hold any seats in parliament, it is expected to play an important role during the campaigning for its chosen candidate at the presidential election scheduled for February 2024.

Until now, Kaesang has been best known to Indonesians as a YouTuber and entrepreneur. According to Wikipedia, he “is active in the culinary business, owning a chain of banana-centered outlets operating in several cities in Indonesia. He also created a clothing line, featuring images of tadpoles.” On top of that he owns a 40 percent stake in the PT Persis Solo Saestu soccer club.

In January, the 28-year-old expressed his interest in following his father into politics, but didn’t join the PSI until two days before his appointment as its leader. The appointment of the political neophyte to a position of relative power and authority, essentially on the basis of his father’s public aura, encapsulates the dynastic political practices that have been a feature of Indonesian politics since the country’s independence.

While Jokowi was notable for being the first Indonesian president not to hail from the military establishment or an established political family, he is seemingly ensuring that his legacy continues through his children and close relatives. Jokowi’s second and final term will come to an end next October.

In 2020, Jokowi’s elder son Gibran Rakabuming Raka was elected mayor of Surakarta in Central Java, a position that his father held between 2005 and 2012. (A similar line of succession recently took place in the Philippines, where President Rodrigo Duterte’s daughter Sara succeeded him as mayor of Davao City in Mindanao.) He has also been spoken of as a possible vice presidential candidate for 2024. Meanwhile, Jokowi’s son-in-law Bobby Nasution is serving his first term as mayor of Medan, an important city on the island of Sumatra.

Jokowi’s two presidential predecessors have both established their children in positions of prominence in regional and national politics. Megawati Sukarnoputri, the daughter of the country’s first president, Sukarno, served as president between 2001 and 2004 and remains the chairperson of Indonesia’s largest political party, Jokowi’s Indonesian Democratic Party of Struggle (PDI-P). In turn, her daughter Puan Maharani has served as speaker of parliament and was earlier this year mooted as a potential presidential candidate for the PDI-P in next year’s election.

Yudhoyono likewise has children with impressive political CVs. His eldest son, Agus Harimurti Yudhoyono, has served as a member of parliament and as governor of Jakarta, and heads the Democratic Party, which currently occupies 54 seats in the House of Representatives. One of these seats is occupied by his younger brother Edhie Baskoro Yudhoyono, 42, who has also served as the party’s secretary-general.

As in many East and Southeast Asian nations, political dynasties are rooted in the kinship and patronage networks that predominate in many parts of the region. Indonesia, Noory Okthariza of Jakarta’s Center for Strategic and International Studies, wrote in December 2020 that political dynasties in Indonesia had emerged in part from political families’ need “to maintain existing networks formed from formal and informal relationships between financiers, enforcers, activists, and individual political leaders.”

As Jemma Purdey argued in a recent article for East Asia Forum, the challenge facing Jokowi is that he does not control a political party through which his family’s prominence can be institutionalized, even though he enjoys (for now) the support of Megawati’s PDI-P. Crucial to the longevity of the Jokowi dynasty, Purdey wrote, was to “‘bed down’ its successor generation” at next year’s election, which will see Jokowi’s successor elected alongside hundreds of members of regional and national parliaments.

“For the second generation of the Jokowi dynasty, decisions about where and with whom they set their electoral targets are crucial,” she wrote. “One strategic misstep can end in disaster. The Widodo family do not currently have the luxury of a family party machine to fall back on.”

Leaving aside the possibly corrosive impacts on Indonesia’s young democracy, the interesting question is how and to what extent the successful creation of a political dynasty will undermine one of Jokowi’s key initial appeals: his unpretentious bearing, and the fact that he hailed from outside the galaxy of established political clans. However, if the president’s current popularity is any guide – his approval rating reached an all-time high of 76.2 percent in January – it will not be hard to enclose the old wine of nepotism in new political bottles.