The latest BRICS summit held in South Africa, despite being the 15th edition, brought with it a great deal of excitement – as well as trepidation about a potential new, divided world order – through the bloc’s announced expansion. Copious pages of analysis are continuing to be devoted to it today. But another change was in the works at the same time, although it went relatively unnoticed – hidden in plain sight within a special China-Africa Leaders’ Roundtable Dialogue, held on the sidelines of the summit.

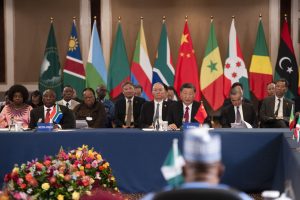

Co-chaired by South Africa’s President Cyril Ramaphosa and China’s President Xi Jinping on August 24, the dialogue only lasted a few hours. Several other African heads of state and government joined, notably Senegal’s President Macky Sall, the current co-chair of the Forum of China Africa Cooperation (FOCAC), which will next meet in Beijing in 2024.

This was the first time many of the presidents had seen Xi in person since the pandemic, as the Chinese leader did not attend the last FOCAC summit, held in Dakar in 2021, in person. So the dialogue represented an important opportunity for African governments to reiterate their key asks from China, and for the Chinese government to do the same.

At a first glance, the new commitments to deepening cooperation presented the main outcomes and biggest shift of the dialogue. In line with new Chinese domestic policy, there was a strong call to focus on modernization underpinned by three new initiatives.

First, the “Initiative on Supporting Africa’s Industrialization” is intended to utilize existing structures of FOCAC, the Belt and Road Initiatives, and the new Global Development Initiative (GDI) to channel resources for assistance, investment, and financing programs of manufacturing and value-addition. These are major priorities for every African country, especially post-pandemic. The African Union adopted the “Accelerated Industrial Development for Africa” as well as the Africa Mining Vision (AMV) back in 2008 and industrialization was the main topic of the 2022 special African Union summit in Niger.

Second, the “Plan for China Supporting Africa’s Agricultural Modernization” looks to expand grain cultivation, provide emergency food assistance, and encourage Chinese companies to boost agricultural investment in Africa. This initiative is particularly important in the context of African goals for food sovereignty – a push for African countries to be able to feed themselves.

Third, the “Plan for China-Africa Cooperation on Talent Development” is particularly interesting. It sees China planning to train 500 principals and high-level teachers in vocational schools, as well as 10,000 technical personnel per year in both vocational skills and the Chinese language. The initiative also incorporated a plan to invite 20,000 African government officials and technicians to China for participation in workshops and seminars. Collectively, these new human capital related ideas represents a major shift from previous FOCAC commitments, which have primarily focused on African students studying in China.

However, while these three initiatives will certainly be very interesting to track, it was some other language from Xi that really struck a new note, especially in the context of BRICS and its links to global governance and multilateralism.

What stood out was the Chinese language on Africa’s own institutions and voice in multilateralism.

Using entirely new phrasing, Xi referred for the first time to the Pan-African Payment and Settlement System (PAPSS) – a structure launched in 2022 to bypass SWIFT for African local currency exchanges (which China itself does through its Cross-Border Interbank Payment System (CIPS) – and the African Union of Broadcasting, established in 1962 and revamped in 2006. Xi went further to state that China “will support Africa in speaking with one voice on international affairs and continuously elevating its international standing.”

The language is notable. From 2013, when Xi assumed the presidency, until 2021, language on shared goals for global governance reform in formal China-Africa documents (such as FOCAC declarations) had been fairly broad and, in many ways, less ambitious than previous commitments made from 2006 to 2012, for instance. However, 2021 marked a shift. In the declaration following that FOCAC summit, language on global governance reform was more detailed than ever, with references to shifts that the United Nations, international financial institutions, and others needed to make to meet African and, to some degree, Chinese needs.

Then, in August 2022, during a FOCAC follow-up meeting, Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi announced that China supported the full permanent membership of the African Union in the G-20, becoming the first country to do so at the leadership level. Xi later reiterated that same position in November 2022 at the G-20 Summit in Bali. Since then, G-20 member after G-20 member has also adopted this position, with India’s Prime Minister Narendra Modi most recently writing to all his G-20 counterparts to call for this to be an outcome of the Delhi summit later this week.

The positive reception from Africans in particular to the global governance-related FOCAC commitments, the G-20 announcement, and its global impact have no doubt emboldened both African and Chinese governments in pushing for African countries to have stronger representation, roles, and voice in a wide range of plurilateral and multilateral organizations. That’s what the language following the latest China-Africa dialogue reflects. Even the BRICS expansion reflects this – much ink has been spilled about the representation of the MIddle East among the new members, but it’s equally notable that two of the six new BRICS members are African countries.

Coming out of the China-Africa leaders dialogue in Johannesburg, then, the big question is which institution(s) will be the next target for Africa-China coordination on global governance reform. That’s the change we should all be gearing up for.