When U.S. President Joe Biden arrives in Hanoi on September 10, U.S.-Vietnam relations will likely be upgraded to a “comprehensive strategic partnership.” According to inside sources, the leadership of the Communist Party of Vietnam (CPV) has decided to take bilateral relations with the United States to the highest level of Vietnam’s diplomatic hierarchy. This could not have happened soon enough.

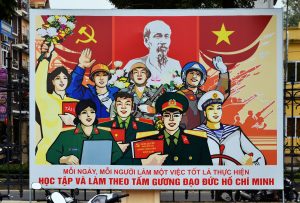

Hanoi’s reluctance to formalize a strategic relationship with Washington is well known. Observers have long noted the CPV’s fear of offending Beijing and its concerns that a closer relationship with the U.S. could foster “peaceful evolution” away from communist rule. So why is Hanoi taking the public step of upgrading U.S. ties to the same level as historical partners China and Russia, leapfrogging the lower level of “strategic partnership”?

Some analysts have previously commended Hanoi’s hedging strategy for striking a balance between China and the United States. But implicit in this approach is that this is a hedging strategy for the CPV – one that allows it to continue drawing political support from Beijing while gaining the economic and security benefits of ties with the West.

This strategy is deeply unpopular with a large portion of the Vietnamese population, which tends to be overwhelmingly pro-U.S. and anti-China. As the head of a one-party state, the communist government can dismiss public opinion, but it can’t ignore the will of the people completely. Moreover, the party leadership has acknowledged that the status quo is untenable and that Vietnam needs a more balanced foreign policy that is less overtly tilted toward China.

After Taiwan, Vietnam is perhaps the country most at risk from a revisionist China. Beijing continues to assert sovereignty over virtually the entire South China Sea, encompassing islands claimed or held by Vietnam and much of its exclusive economic zone. This constitutes a grave threat to the nation’s fishermen and offshore oil and gas fields, to say nothing of its independence and territorial integrity.

Beyond security, enhanced ties with Washington could bring further economic benefits and progress. The U.S. is already Vietnam’s largest export market and the top destination for Vietnamese students studying abroad. Many of Vietnam’s existential challenges – from a sinking Mekong Delta to an underdeveloped civil society – require bold and creative solutions. The Beijing model is unlikely to be the source of best practices, unless the goal is maintaining political power for a small minority. China is also facing serious economic difficulties which could portend a long-term stagnation.

The Russian invasion of Ukraine has brought clarity to the security choices of many nations who understandably want good relations with a powerful neighbor. But for Hanoi, the past 18 months have been a whirlwind of angst and indecision. Each time Vietnam had the chance to uphold international law at the United Nations, its diplomats have abstained on key resolutions condemning the Russian invasion. The Hanoi leadership didn’t want to take a position, even though Vietnam’s national interest is for a world where bigger powers don’t unilaterally redraw the maps to the detriment of smaller states. Within a changing international environment, it has become increasingly hard for Vietnam to muddle through.

And so, the upcoming Biden visit is an opportunity for Vietnam to update its international relations to take account of the changing international circumstances. Along with Vietnam’s “special relationships” with Cuba, Laos, and Cambodia, the current rubric of “comprehensive,” “strategic,” and “comprehensive strategic” partnerships is contrived and outdated. It is particularly nonsensical to have a “comprehensive strategic relationship” with China, which represents an existential threat to Vietnam.

To be sure, Hanoi will continue to assuage Beijing and underscore the CPV’s party-to-party relationship with the Chinese Communist Party as “comrades and brothers.” Just days before President Biden’s arrival in Vietnam, CPV chief Nguyen Phu Trong took a much-publicized tour of the Vietnam-China border with Chinese Ambassador Xiong Bo to emphasize fraternal relations. And following the Biden trip, Xi Jinping is expected to be accorded a state visit to Vietnam.

Nevertheless, between the dueling visions of the Belt and Road Initiative and the “free and open Indo-Pacific,” it’s becoming clear where Vietnam’s future should lie. Just as Deng Xiaoping once said, “It doesn’t matter whether a cat is black or white, as long as it catches mice,” the Hanoi leadership needs to reorient Vietnam’s foreign policy in pursuit of the country’s strategic and comprehensive interests.

For the U.S., the decision to engage Vietnam is the right one. With its dynamic population and strategic location, Vietnam has the potential to be the cornerstone of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations and a key contributor to a freer and more open Indo-Pacific. But whether Vietnam can realize its full potential depends on more than just the naming convention for its external relations. Ultimately, the best guarantors of a free and open Indo-Pacific are free and open societies.

In a year where Finland rejected “Finlandization” under the thumb of Russia, Vietnam surely can move beyond its old paradigms and self-imposed limitations.