Last week, Sri Lanka’s Minister for Power and Energy Kanchana Wijesekera presented a cabinet paper seeking permission to convert a $442-million wind power project agreement in northern Sri Lanka with the Adani Group into a government-to-government (G2G) arrangement. Under the agreement, Adani Green Energy is to build a facility in Mannar that is slated to generate 250 megawatts (MW) of electricity and another at Pooneryn to produce 100 MW. The agreement for both projects was originally inked in March 2022.

The plan to convert the agreement to a G2G arrangement was done to circumvent the legal challenges associated with awarding the project to a private company without following an open tendering process as dictated by laws governing power generation in Sri Lanka.

It must be noted, however, that the Sri Lankan government has always insisted that it considers dealings with the Adani Group as agreements with the Indian government.

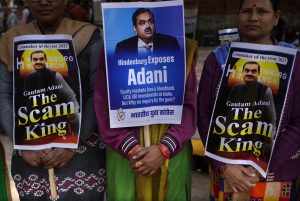

For example, when he was in New Delhi for the G-20 foreign ministers’ summit a few months ago and shortly after the Hindenburg Report, which alleged that the Adani Group was engaged in “brazen stock manipulation,” was made public, Sri Lanka’s Foreign Minister Ali Sabry told The Hindu that the government is not worried about the implementation of large-scale projects being handled in Sri Lanka by Adani companies because it is a “government-to-government kind of project.”

In mid-2022, the former head of the Ceylon Electricity Board (CEB), a state-owned electricity producer and distributor, told a parliamentary committee that India’s Prime Minister Narendra Modi pressurized then-President Gotabaya Rajapaksa to grant the Adani Group access to renewable power projects in Sri Lanka.

Many Sri Lankans believe that Gautam Adani, chairman of the Adani Group, is an extension of the Modi administration and view his projects as representing India’s geopolitical ambitions on the island. However, the official stance of the Indian government is that there is no special relationship between the Modi administration and the Adani Group.

Repeated claims to the contrary by the Sri Lankan government have caused the Modi administration many inconveniences. It has triggered opposition criticism of Prime Minister Modi’s proximity to Adani and the latter functioning as an extension of the government.

The power ministry’s presentation of a cabinet paper seeking to officially convert the power agreement with the Adani Group to a G2G arrangement appears to have ruffled feathers in New Delhi.

India’s Defense Minister Rajnath Singh, who was scheduled to visit Sri Lanka on September 11, canceled his visit last week. While New Delhi did not provide reasons for the eleventh-hour change of plans, the decision could be related to the Adani saga.

According to Indika Perera, an attorney-at-law and expert in conflict resolution, a section of the Sri Lankan bureaucracy is of the view that India canceled Singh’s visit due to apprehensions related to Sri Lankan attempts to make dealings with Adani officially G2G.

“We have said that it is a G2G arrangement verbally many times and this caused some embarrassment to India but with a cabinet paper, we have made it official,” Perera told The Diplomat.

Apparently, “the Indian government was displeased when the Sri Lankan Minister for Power tried to convert the agreement with Adani Green Energy Limited for the execution of renewable energy projects in the island’s Northern Province to a government-to-governmental deal,” Perera said.

However, another group of officials believes that the Indian defense minister canceled his visit because Sri Lanka has permitted the Chinese marine research vessel Shi Yan 6 to dock at Colombo and Hambantota ports in October. The docking of the Chinese vessel Yuan Wang 5 at Hambantota port last year, despite New Delhi’s objections, had strained India-Sri Lanka relations.

“If we are not following an open tender process on power generation, we can only do that with a government,” Charitha Herath, a parliamentarian from the Freedom People’s Congress (FPC) told The Diplomat.

In the cabinet paper, Wijesekera has urged the government to let the Adani Group develop the 400-kilowatt backbone transmission line from Kilinochchi to Pooneryn, Herath said, pointing out that “this is also a deviation from the Electricity Act.” The minister has justified the proposal to build the power line by saying the project will cost $ 135 million and that the government cannot provide the required funding for the project, he said.

Herath said that around 2016, Sri Lanka decided to build two LNG power plants to meet the country’s growing power needs. In 2021, the CEB called for bids to secure the supply of LNG for the power plants that are to be built. Initially, the United States-based New Fortress Energy was to supply the LNG, however following continuous resistance by unions and the ouster of Rajapaksa, the government decided to cancel the agreement.

In the above-mentioned cabinet proposal, the Minister for Power has asked the cabinet to cancel the tender and to authorize him to procure LNG needed for the power plants.

The LNG must be procured from another government, Herath said.

“The next cabinet paper will surely name India as the government that we will get LNG from. Recent discussions on Sri Lanka’s future energy production revolve around Adani,” he added.