Sri Lanka’s President Ranil Wickremesinghe recently appointed a Green Finance Committee to pioneer a roadmap for sustainable finance and emphasized the need for resource mobilization from multilateral development banks and the private sector to achieve climate change targets.

As part of Sri Lanka’s Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs), updated in 2021, the government committed to supplying 70 percent of its domestic electricity with renewable energy sources by 2030, with the longer-term goal of achieving a full renewable electricity supply by 2050. However, given the current fiscal constraints imposed by the economic crisis and the scale of investment required to address structural imbalances in the energy sector, it is becoming increasingly challenging to achieve this target. Therefore, policymakers must explore innovative financing solutions to maintain investments in this sector and facilitate the essential green energy transition.

The recent agreement between the governments of Portugal and Cabo Verde signals to Sri Lanka that there may be such a solution. In early 2023, it emerged that Portugal had agreed to forgive a portion of Cabo Verde’s bilateral debt in exchange for commitments to biodiversity conservation and renewable energy development. Although these negotiations are in their early stages, they demonstrate that incentive frameworks exist and that there is an intersection point between debt, climate, and renewable energy priorities.

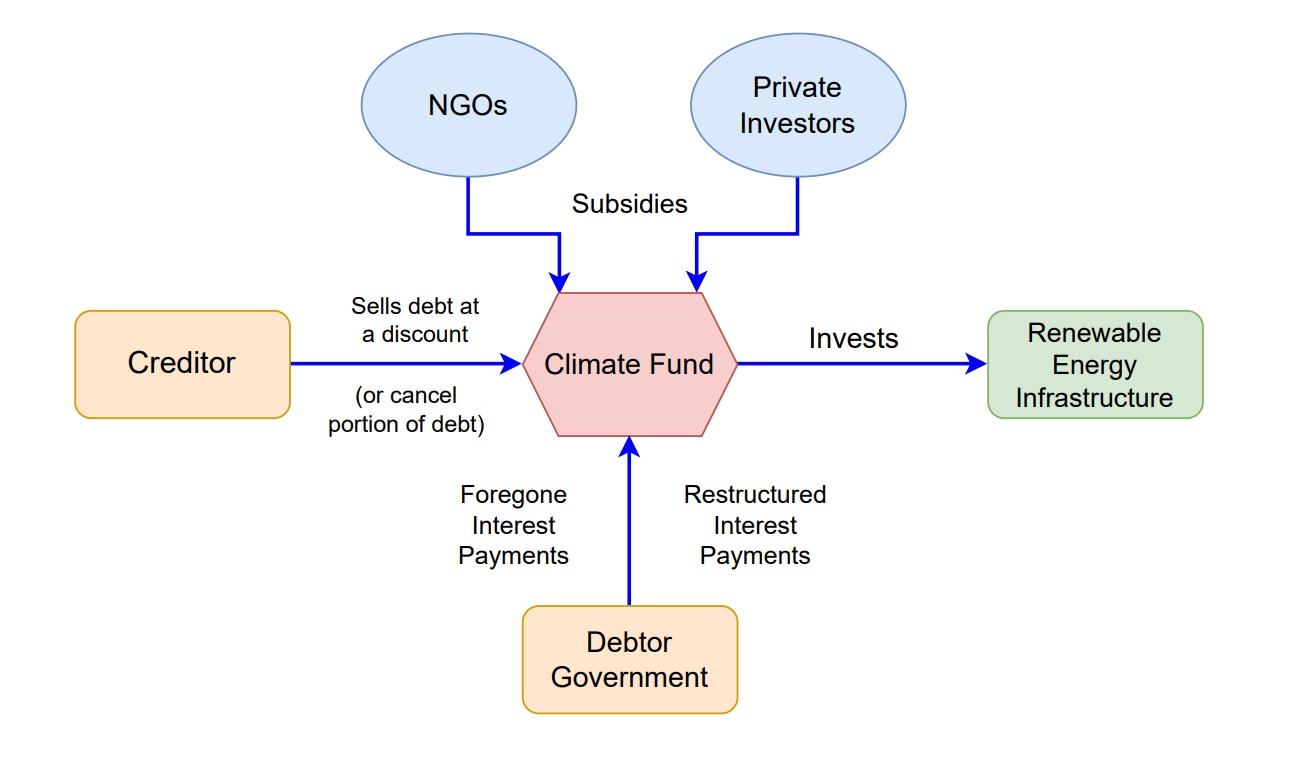

A “debt-for-renewables” swap would reallocate foregone debt repayments toward public sector investments in renewable energy infrastructure and support the diversification of the energy sector. Much like debt-for-nature swaps, a “debt-for-renewables” swap would reallocate debt repayments to a more productive sector and generate significant economic multiplier effects as a result of a more reliable, efficient, and autonomous energy sector.

Swapping Debt for Nature

Debt-for-nature swaps enable heavily indebted countries to restructure a portion of their external debt onto more favorable terms in exchange for environmental commitments. This typically involves creditors canceling or reducing unsustainable debt while creating obligations to protect the local environment using freed-up funds. This eliminates the significant opportunity cost of debt repayments by redirecting funds to mutually agreed conservation projects with more concessional repayment terms.

Servicing foreign debt is incredibly expensive for developing countries not only because of the absolute cost associated with repayments but also due to the significant opportunity costs. Developing countries forgo investments in essential infrastructure, social services, and public investments that have high economic and social returns to service debt obligations without direct economic outcomes.

In recent years, these opportunity costs have also materialized through environmental challenges and limiting essential investments in climate change mitigation and adaptation. This new dimension exacerbates the costs of the global debt crisis, as developing countries risk falling into a “debt-climate” trap if they are unable to finance climate-resilient investments due to unsustainable debt burdens. Debt-for-nature swaps provide governments with an opportunity to finance investments in climate change adaptation and mitigation without taking on new debt.

Recent debt-for-nature swaps in Belize and Seychelles primarily targeted marine projects and reallocated funding to long-term biodiversity and conservation projects. The Nature Conservancy (TNC) financed the repurchase of external debt from creditors at a discounted rate and provided more concessional repayment terms, which was combined with a commitment from debtor governments to finance conservation projects using the freed-up funds.

Belize and Seychelles also leveraged their strong blue tourism sectors to incentivize investors to engage in debt-for-nature swaps, as funding marine conservation preserves natural assets that are vital to ocean tourism. The tourism industry guaranteed a sustainable source of government revenue and assured creditors that debtor governments would be able to service their debt obligations alongside environmental commitments.

The success of debt-for-nature swaps in Belize and Seychelles was driven by already established commitments to marine conservation and the economic multiplier effects associated with fulfilling them. Rather than prioritizing debt relief, debt-distressed governments must identify debt swaps as an instrument to maintain investments in environmental conservation and climate-resilient infrastructure by removing the opportunity costs of debt repayments. Strong, ambitious, and achievable environmental targets give debtor governments credibility to pursue debt-for-nature swaps; without clear targets, they risk overcommitting to environmental obligations and falling short, which could create further debt problems in the long run if commitments are not fulfilled.

The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and Sri Lanka’s Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) provide a strong foundation for targeted, productive investments and must be leveraged to reassure creditors that a long-term approach to finance is sustainable. At the recent Sustainable Development Forum, Wickremesinghe emphasized the importance of finding resources to achieve the SDGs and combat climate change. Debt swap instruments must play an important role in financing sustainable investments, especially to address some of the pressing challenges in Sri Lanka’s most vulnerable sectors.

Sri Lanka’s Green Energy Transition

Addressing structural imbalances in the domestic electricity sector is vital for both climate targets and economic development. The economic crisis demonstrated Sri Lanka’s unsustainable dependence on fuel imports from abroad (around two-thirds of the national energy supply comes from imported fossil fuels); because Sri Lanka relies so heavily on international markets that trade predominantly in U.S. dollars, foreign exchange reserves are required to purchase fuel. When the government exhausted those reserves, fuel supply was limited, and this posed significant challenges to households and businesses on the island.

This overdependence on imported fuel is also exacerbated by inadequate energy diversification and a lack of renewable energy infrastructure in Sri Lanka. Between 1991 and 2014, Sri Lanka’s net energy imports as a share of total energy consumption increased from 25 percent to 50 percent, while the share of energy generated by renewable energy sources plummeted from 80 percent to an all-time-low of 45 percent of total final energy consumption in 2016. Sri Lanka has shifted away from domestic hydroelectric power toward fossil fuels in recent decades, which has created a fragile energy sector that is overdependent on imported fossil fuels.

Unpredictable access to fuel and electricity poses significant challenges for economic development, as energy is essential for businesses and households to function. Creating a more sustainable electricity sector requires significant investment in energy infrastructure to create more energy autonomy, as well as stabilizing and managing the cost of energy in the domestic market. Given that Sri Lanka is not naturally endowed with fossil fuels and other traditional sources of energy, renewable energy infrastructure is essential to build the capacity to supply electricity to the national grid.

Energy sector diversification must come through a blended finance approach; public investments in domestic energy infrastructure and the establishment of strong regulatory frameworks and governance signals to private investors that the government is committed to its NDCs and will reward private sector involvement in its pursuit of a green transition.

Swapping Debt for Renewable Energy

As part of diversifying the energy sector and supplying clean electricity to the national grid, creditors stand to benefit from revenues generated through the sale of electricity and thus secure guaranteed debt repayments in this form. This can make debt servicing more sustainable in the long run as more generous interest rates, longer-term repayment schedules, and improvements in the productive capacity of the economy relieve pressure on the government to overextend itself to service external debt. Much like how tourism taxes and revenues reassured creditors in Belize’s and Seychelles’ debt-for-nature agreements, the Sri Lankan government can leverage revenue shares from renewable energy sales as a guarantee of creditor repayment and thus improve their credibility in the markets.

To maximize the effectiveness of debt swaps, the government must target the domestic energy sector. Structural imbalances at the heart of the energy sector require serious government intervention and a “debt-for-renewables” swap provides a unique opportunity to finance essential investments without taking on more debt. A reliable and affordable domestic electricity supply, powered by renewable energy, is an essential component of sustainable economic development and the economic multiplier effects of this approach go far beyond the intersection of debt, climate, and energy priorities.

The Need for Climate Finance

Sri Lanka will not fulfill its renewable energy commitments under current economic conditions. The government must explore innovative solutions to the climate, energy, and debt crises; a “debt-for-renewables” swap exists at the intersection of these challenges. The government must establish a coordinated response across ministries to properly evaluate the potential of debt swaps, focusing specifically on sectors with significant economic multiplier effects that offset the transaction costs of such complex negotiations.

Previous case studies and ongoing negotiations in several highly indebted countries demonstrate that incentive structures exist for such agreements, so Sri Lanka must engage holistically with creditors to explore comprehensive solutions to the ongoing crisis. Debt swap instruments have the potential to unlock funding for renewable energy investments, but the government must establish credibility through strong commitments to its energy sector NDCs. This must be complemented by strong governance and regulatory frameworks that create a more attractive environment for private creditors.

As the government contends with debt and climate crises, climate finance must be at the forefront of Sri Lanka’s debt restructuring processes. However, it must be part of a comprehensive, transparent, and coordinated response from all lenders to create a more sustainable debt structure for economic recovery, without undermining global campaigns for debt justice.

This article is based on a policy brief titled: “Debt-for-Renewables’ Swaps: How to Address Climate, Debt and Energy Sector Vulnerabilities in Sri Lanka” published by Lakshman Kadirgamar Institute of International Relations and Strategic Studies.