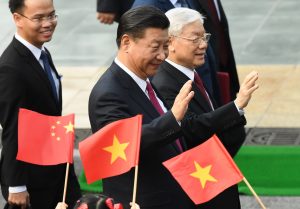

Vietnam and China are reportedly preparing for a possible visit by China’s President Xi Jinping to Vietnam at the end of this month or early next. The visit, if it happens, will come around two months after U.S. President Joe Biden’s visit to Hanoi, during which he announced the elevation of U.S.-Vietnam ties to a Comprehensive Strategic Partnership, and one year after Communist Party of Vietnam General Secretary Nguyen Phu Trong last visited Beijing in November 2022, the first visit by a foreign leader to China after the COVID-19 pandemic.

One item reportedly on the agenda of Xi’s mooted Hanoi visit is the elevation of Vietnam-China ties, especially the inclusion of the phrase “community of common destiny” in the joint statement, to signal that China wants to put Vietnam at the “highest level of bilateral relations for the Xi Jinping administration.”

There has been understandable pushback against the inclusion of such a phrase from Vietnam, especially after China wanted to include it during Xi’s last visit to Vietnam in 2017, due to concerns that such a move could be interpreted as Vietnam joining a China-led coalition against the United States. Vietnam’s pushback to China’s proposal is similar to its earlier resistance against the U.S. efforts to draw Vietnam into an anti-China coalition. Still, whether or not Vietnam agrees to include such a phrase in the joint statement, Xi’s visit would represent a victory for Vietnam’s omnidirectional foreign policy. On a deeper level, Xi’s visit is even more important for Vietnam’s security than Biden’s visit.

As I’ve argued previously, the China-Vietnam relationship is an asymmetrical one, in which China holds the key to Vietnam’s foreign policy. When China tolerates Vietnam’s agency, Vietnam is able to cultivate ties with other extra-regional powers and diversify its foreign relations. When China does not tolerate Vietnam’s agency due to a fear of Vietnam aligning with other extra-regional powers against Chinese interests, Vietnam suffers from diplomatic isolation and is subject to military as well as economic coercion.

As a result, for Vietnam, it is vital to obtain Chinese tolerance for its foreign policy initiatives, which explains why Vietnamese leaders always inform and persuade Chinese counterparts of their benign intentions before every outreach to the United States. Vietnamese efforts to assuage China resulted in the absence of any mentions of China in the joint statement issued after the Biden-Trong meeting. It was also reflected in Biden’s repeated affirmation that the U.S. does not want to contain China while in Hanoi. Xi’s possible visit after Biden’s demonstrates that Hanoi’s efforts to reassure China have borne fruit.

But on a fundamental level, why does Vietnam have to go to great lengths to ensure that China does not misunderstand Vietnam’s actions, even if that means delaying other important foreign policy initiatives? This is because Vietnam and China are looking at their bilateral relationship through two different lenses. From the Chinese perspective, Vietnam belongs to China’s sphere of influence and any Vietnamese attempt to lessen Chinese influence demands a Chinese reaction. In contrast, Vietnam wants to assert its agency and any attempt to do so aims at deterring Chinese encroachments on its security. Within the confines of the China-Vietnam relationship, China operates according to a spiral model of war, under which Beijing is willing to exert punishment with the expectation that Vietnam is going to fall back in line. Conversely, Vietnam operates according to a deterrence model of war, perceiving that the best way to impede Chinese punishments is to stand firm, not to appease Chinese demands. Consequently, whatever Vietnam does to deter Chinese reactions actually feeds into China’s determination to punish Vietnam. Vietnam’s handling of its relations with China in the late 1970s provides a useful lesson for the understanding of this dynamic.

Contrary to some suggestions, Vietnam did not intend to annex Laos and Cambodia under an “Indochinese Federation” after the Vietnam War. Hanoi’s primary occupation was with economic integration, reconstruction, and industrialization for the distinct northern and the southern economies. Between 1975 and 1977, Vietnam was exploring diplomatic normalization with the United States on the condition that the United States paid war reparations as promised under the 1973 Paris Peace Accords. It also became the first communist country to join the International Monetary Fund in 1976. Hanoi sought economic aid from both the Soviet Union and China, while resisting Soviet pressure to join the Council for Mutual Economic Assistance (Comecon) and remaining neutral in the Sino-Soviet Split.

Vietnam’s emphasis on economic development only changed after the Khmer Rouge regime in Cambodia launched a series of attacks along its southwestern border beginning in April 1977. Vietnam had to respond militarily but it did so in a restrained manner. It also engaged China in the hope that Beijing would become a mediator in the Vietnam-Cambodia conflict. To Vietnam’s disappointment, its efforts to find a diplomatic solution to the border disputes through Beijing in October and November 1977 did not stop the Khmer Rouge from attacking Vietnam and cutting diplomatic relations with it on December 31, 1977. At that stage, the Vietnamese leadership concluded that Beijing planned to use the Khmer Rouge against Vietnam. Vietnam’s acquiescence to a Chinese role in Indochina did not elicit better behavior from China. Appeasement did not work so Vietnam now had to stand firm.

As such, to prevent further Khmer Rouge attacks after all diplomatic options were exhausted, Vietnam resolved to remove Pol Pot by force in February 1978. Vietnam was also aware of the possibility of a Chinese reaction and it reached out to the Soviet Union to deter Chinese punishments after trying to maintain a diplomatic balance between 1975 and 1977. After Hanoi joined Comecon in June 1978, China ended all economic aid to Vietnam.

Vietnam joined a military alliance with the Soviet Union in November to protect itself from the China-Khmer Rouge alliance, not to fulfill its alleged hegemonic ambitions. It even dropped the demands for war reparations from the United States in September to hasten the normalization process in anticipation of Chinese punishment. On the contrary, China saw Vietnam’s assertion of its agency via a security partnership with the Soviet Union as a spiral and threatened to punish Vietnam. In December, the People’s Daily wrote, “we wish to warn the Vietnamese authorities that if they, emboldened by Moscow’s support, try to seek a foot after gaining an inch, and continue to act in this unbridled fashion, they will decidedly meet with the punishment they deserve.” China viewed Vietnam’s “emboldenment” via the alliance with the Soviet Union as a spiral towards a conflict.

In February 1979, China launched an invasion of northern Vietnam to retaliate for the toppling of the Khmer Rouge by a Vietnamese invasion one month earlier. For Vietnam, the Chinese invasion was a deterrence failure because the alliance with the Soviet Union could not prevent it; for China, it was a necessary escalation to “teach Vietnam a lesson” and make Hanoi fall back in line. In the aftermath, Chinese punishments intended to prevent Vietnam from siding with the Soviet Union contrarily solidified Hanoi’s security cooperation with Moscow, at least before the Soviet Union and China began their own normalization process in 1986. Vietnam’s standing firm in the face of Chinese coercion also justified Chinese exerting more military pressure in both Cambodia and Vietnam’s northern border to bleed Hanoi white throughout the 1980s. Neither Vietnam nor China got what they wanted after 1979 simply because they were viewing the relationship from two different models of war.

If history offers any lessons, it is that Vietnamese acquiescence needs to meet Chinese tolerance to avoid a total breakdown in the bilateral relationship. Vietnam’s ongoing efforts to upgrade ties with the United States are intended to deter Chinese encroachments on its maritime sovereignty, not to help Vietnam fulfill any revisionist ambitions. If China perceives Vietnam’s behaviors not as a deterrent to Chinese bullying but as a spiral towards a future China-Vietnam conflict, it can create a self-fulfilling prophecy in which its actions to prevent an enhancement of a U.S.-Vietnam security partnership merely strengthen the case for one.

On the other hand, if Vietnam fails to convince China that Hanoi’s actions do not constitute a spiral towards more escalation, Hanoi’s moves to upgrade ties with the United States to deter Chinese bullying only increase the possibility of a deterrence failure as China ramps up its coercion of Vietnam in response to China-perceived Hanoi’s recalcitrance. Unfortunately for Vietnam, as a small power living next to a giant, it bears the burden of proof in this relationship. Failing to reassure China can easily neutralize all Vietnamese efforts to upgrade ties with the United States because it is cheaper and easier for China to punish Vietnam than for Vietnam to defend itself against those punishments, even with U.S. assistance. As such, Vietnam must always prioritize its relationship with China over that with the United States because Vietnam has a small margin of error.

Xi’s visit to Hanoi, should it eventuate, will thus be a demonstration of China’s tolerance of Vietnamese foreign policy initiatives, which is offered in exchange for Vietnam’s acquiescence and efforts to inform and reassure China of its benign intentions. If Vietnam agrees to join China’s “community of common destiny,” such a move should not be seen as Hanoi joining a China-led coalition against the United States but as compensation to Beijing for “leapfrogging” its ties with the United States straight to a Comprehensive Strategic Partnership. The worst outcome for Vietnam is not Chinese pressure for it to join more China-led initiatives, but a situation in which China no longer invites Vietnam to join and concludes that Vietnam’s actions to foster ties with extra-regional powers constitute a spiral towards a China-Vietnam conflict.