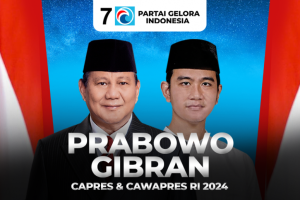

Yesterday’s announcement that Gibran Rakabuming Raka, the eldest son of President Joko “Jokowi” Widodo, will serve as the vice-presidential running-mate of Prabowo Subianto, chairman of the Greater Indonesia Movement Party (Gerindra), has stirred the political cauldron in Indonesia. This significant move raises questions about democracy, dynastic politics, and youth representation in the archipelago’s political landscape.

To an onlooker, this move betrays a dynastic footprint. Indonesia’s democracy, vibrant and alive since the fall of Suharto in 1998, has always teetered between a pure democratic ethos and the lure of centralized power. Jokowi himself can be seen as a representative of grassroots democracy. His rapid journey from being a furniture entrepreneur to the mayor of Surakarta, the mayor of the capital Jakarta, and then to the presidency, underscored the narrative that anyone could aim for the top office in Indonesia.

However, with Gibran’s ascent over the past few years, there has been a subtle shift. While the young mayor of Surakarta certainly carries political weight, being the son of a sitting president offers advantages that other candidates can hardly contest. It rings particularly true when one considers that Gibran is supported by the full strength of Prabowo’s Advanced Indonesia Coalition, including parties helmed by Jokowi’s family.

This turn of events raises a further question. With Gibran’s entry into the February 14 electoral race, the perceived impartiality and credibility of Jokowi’s presidential tenure are set to come under close critical examination. The very sanctity of the electoral process is potentially imperiled, inviting contemplation on the likelihood of Jokowi leveraging state apparatuses to bolster his son’s electoral fortunes.

The Constitutional Court’s recent ruling to lower the age bar for presidential and vice-presidential candidates, provided they have been elected to regional or local office – the decision that opened the way to the 36-year-old Gibran running for the vice presidency – has been seen by many as a nod to Indonesia’s burgeoning young population. By 2024, 60 percent of the electorate will be millennials and Gen Z, a figure too significant for politicians to ignore.

The lawsuit for this change was filed by the Indonesian Solidarity Party, whose general chairman is now Kaesang Pangarep, Gibran’s younger brother, though Kaesang was not the chairman of the party when the lawsuit was filed. It is notable also that the chief judge of the Constitutional Court, Anwar Usman, is a brother-in-law of Jokowi. Given these familial ties, allegations of nepotism and political dynasties have been inevitable. Gibran’s candidacy can therefore be interpreted both as an effort to bridge the generational gap and as a manifestation of familial and political influence.

Historically, youth movements in Indonesia have played transformative roles. The Sumpah Pemuda (Youth Pledge) of 1928 wasn’t just a declaration but a galvanizing force against colonial rule. Similarly, the Reformasi movement that followed Suharto’s fall in 1998 was dominated by youth and student activists. Contrasting these genuine grassroots movements with Gibran’s rise, one might question whether the spirit of youth representation has remained consistent. The representation of young people should be kept from mere tokenism; to genuinely represent youth, the candidate must echo their aspirations, challenges, and hopes beyond age. Gibran’s appointment risks being seen as a strategic move, leveraging his youth to court young voters while not necessarily representing their true aspirations.

For this reason, the Constitutional Court’s ruling, while ostensibly a nod to Indonesia’s young demographics, was met with skepticism, particularly given that the timing coincided with rumors of Gibran’s candidacy. After this decision, the public’s negative sentiment towards Gibran reflects the perceived manipulation of legal provisions to accommodate political ambitions. It has been viewed by many as an oversight or even recklessness on the part of Prabowo and his coalition. They might have miscalculated the electorate’s reaction by prioritizing strategic alliances over public sentiment.

The perceived nepotism, amplified by the court’s decision, has magnified the public’s scrutiny of Gibran’s candidacy. For many, this move appeared less as a genuine attempt to bridge the generational gap and more as a strategic play to consolidate power.

Prabowo, a seasoned politician and defense minister, has seen the highs and lows of Indonesian politics. Despite his unsuccessful bids for the vice presidency in 2009 and the presidency in 2014 and 2019 against Jokowi, the former general’s resilience is undeniable. This history makes his strategic alignment with Gibran, the son of his former adversary, even more intriguing.

By teaming up with Gibran, Prabowo might be aiming to marry Gerindra’s staunch political and economic agenda with the fresh appeal of the young mayor. The alliance signals more than just political maneuvering; it exemplifies the fluid dynamics of Indonesian politics, where past rivalries can be set aside in the interest of perceived future gains.

The decision of Prabowo and his coalition to elevate Gibran is not a mere product of political convenience; it is a carefully calculated gamble. But why Gibran? On the surface, the alliance seeks to harness Jokowi’s formidable network, a mesh of power, capital, and grassroots volunteers. However, the political landscape is often more complex than it appears.

This move, though seemingly advantageous, risks backfiring spectacularly. Aligning with Gibran could undermine Jokowi’s legacy. The looming specter of dynastic politics, combined with Gibran’s portrayal as a beneficiary of privilege, could alienate the urban middle class and the floating mass among whom Jokowi has remained popular. Once a bastion of Jokowi’s support, this demographic could be driven towards Prabowo’s two presidential rivals, Anies Baswedan and Ganjar Pranowo.

Additionally, such an alignment may diminish the votes from Jokowi’s traditional supporters and Prabowo’s staunch backers. A significant portion of Prabowo’s loyalists from the 2014 and 2019 elections and those opposed to Jokowi might gravitate towards Anies. Given Anies’ consistent positioning as the antithesis to Jokowi and his focus on change rather than continuity, he might appeal more to these voters than Ganjar or Prabowo.

Jokowi’s maneuvers in this chessboard of politics hint at a more profound motivation: a desire to cement his legacy. However, is legacy preservation worth the potential ostracization within the ruling Indonesian Party of Democratic Struggle (PDIP)? In this intricate game, Gibran is more than a pawn or knight; he might well be Jokowi’s proxy rook, strategically placed for future endgames.

For Gibran, the stakes are also personal. He harbors a strong ambition to rule and knows the political risks of familial associations. The experience of Agus Harimurti Yudhoyono (AHY), the son of former President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono, looms in the background. In 2017, AHY vied for the position of governor of Jakarta, but his ambitions were thwarted, arguably because his father was no longer at the helm of power.

Gibran perceives a similar trajectory for himself; if he contemplates running for governor or vice president after Jokowi concludes his term, he might be disadvantaged without the protective shadow of his father’s incumbency. This realization adds urgency to his current political endeavors. A defeat now, while his father still wields power, could foreclose future opportunities for Gibran to ascend the political ladder. It is a balancing act, where Gibran must ensure that his political ambitions stay within his credentials and the electorate’s faith in him.

The real test for Gibran, however, lies ahead. While he enjoys the privilege of dynastic politics, this will also bring scrutiny. As the potential vice president, Gibran must prove that he is more than just Jokowi’s son. Though relatively short, his tenure as the mayor of Surakarta has been notable. However, the challenges at the national level are more complex. From foreign policy to economic decisions, from handling religious complexities to managing the diverse archipelago’s aspirations, the position demands more than just youthful vigor. It requires maturity, wisdom, and an ability to transcend familial advantages.

To sum up, the unfolding political narrative in Indonesia, following the ascension of Gibran, concerns not just a mere candidacy; it is a commentary on the state of its democracy. The alliance of Jokowi and Prabowo to propel a younger face to the vice-presidential seat may seem progressive on the surface. However, as mentioned above, it risks being seen as a cynical politicization of youth, intended to consolidate power rather than genuinely representing the aspirations of the young. This strategy, if successful, could set a troubling precedent for the future of Indonesian democracy, where age becomes a façade for political interests, and genuine representation takes a backseat.

In summary, Indonesia finds itself at a juncture in which the roles of dynastic politics, youth representation, and democratic ideals intersect. The young electorate will play an important role in which direction the country will go next, tasked with discerning genuine representation from political strategy. It is imperative for Indonesia’s democratic future that its youth are represented authentically rather than being used as mere pawns in a larger political game. The nation’s future hinges on preserving the essence of democracy and not letting strategic, dynastic power plays overshadow it.