Amid the decline of global democracy over the past two decades, one country that hasn’t received much attention from geopolitical observers is Cambodia, which has suffered under the rule of political strongman Hun Sen and, more recently, his son Hun Manet, who took over as the country’s prime minister in August. This Southeast Asian nation is playing an increasingly important role in the geopolitical competition between the United States and China.

The most obvious manifestation of the collapse of democratic politics and return of authoritarianism in Cambodia was the outcome of Cambodia’s 2018 general election, compared to the 2013 election. In 2018, Hun Sen’s Cambodian People’s Party (CPP) “won” all 125 seats in parliament. Just five years earlier, Cambodia was on the verge of a power transition: The opposition party, the Cambodia National Rescue Party (CNRP), secured 55 seats with 44.5 percent of the vote, second only to the CPP’s 68 seats with 48.8 percent of the vote. The opposition’s success came amidst widespread allegations by both the opposition and international observers that the ruling party had engaged in widespread electoral fraud.

The 2013 general election and the year-long protests against electoral fraud marked Cambodia’s closest encounter with true democracy since the U.N.-organized elections of 1993. Without the fraud, Cambodia would have experienced a peaceful transfer of power in 2013 and moved closer to a democratic path. Although the political struggle ultimately ended with Hun Sen retaining his leadership position, the election results and the protests demonstrated the depth of the people’s desire for change and significantly undermined Hun Sen’s authoritarian rule. At the time, it seemed that authoritarianism in Cambodia was on the decline, with the corrupt and increasingly unpopular Hun Sen government being voted out of office in the next election as a real possibility.

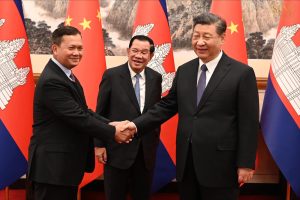

Five years later, however, Cambodia’s democratic progress took a shocking step backward, as Hun Sen established an even more authoritarian system than before 2013. This slide into authoritarianism was confirmed in July 2023, when the CPP was again re-elected in the absence of a recognized opposition party. The “victory” culminated on August 22, when Hun Manet formally took over as the country’s prime minister (the role his father had held since 1985).

There are many reasons for Cambodia’s quashing of democratic aspirations, one of which is the country’s relationship with China.

Hun Sen’s short compromise with the opposition in 2013 and 2014 was influenced not only by the domestic strength of the opposition, but also by fears of international intervention and sanctions. Hun Sen’s closest ally at the time, Vietnam, couldn’t compete with Western countries in terms of economic size or international influence. Hun Sen therefore turned to a rapidly rising China.

Since 2015, Cambodia’s relationship with China has rapidly warmed. China’s strong support for the CPP government emboldened Hun Sen to ignore sanctions from the United States and Europe and to use ruthless methods to suppress the opposition. The warming of Sino-Cambodian relations began with Cambodia’s strong support for China’s position on the South China Sea issue, particularly in the wake of the international arbitration case between China and the Philippines. Cambodia showed an extraordinary level of support for China and repeatedly blocked Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) resolutions on the case.

China’s territorial and maritime disputes with ASEAN countries, along with its desire to counter the growing influence of the United States and India in the South China Sea and surrounding regions, make Southeast Asia strategically important. In China’s “Belt and Road” strategy, the Indochina Peninsula was a crucial part of both the overland “belt” and the maritime “road.” Cambodia became China’s primary target for influence. Both sides had something to gain, and the partnership quickly solidified.

Unlike Western countries, China totally disregards the human rights situation in recipient countries of its aid and aims to please ruling elites while exchanging economic, political, diplomatic, and strategic interests. This type of approach is naturally welcomed by rulers with poor human rights records, and Hun Sen was no exception. During Chinese leader Xi Jinping’s visit to Cambodia in October 2016, the two sides signed 31 agreements, including forgiving 600 million yuan of Cambodia’s debt; increasing bilateral trade from $4.4 billion that year to $5 billion the following year; encouraging Chinese companies to build railways, airports, and other infrastructure in Cambodia; and increasing cooperation in capacity building, investment, agriculture, and water resources. As of July 2020, China had provided nearly $600 million in aid to Cambodia for infrastructure development, education, and healthcare. Cambodia has become China’s closest and most loyal ally in Southeast Asia.

In practice, the United States and its democratic allies have not paid enough attention to human rights abuses in countries where their interests don’t directly conflict. This has allowed autocratic leaders like Hun Sen to act with impunity. In 2015, he used his control of the judiciary to charge then-CNRP leader Sam Rainsy with “inciting social unrest,” claiming that a series of strikes and protests constituted “incitement.” Rainsy subsequently went into exile and never returned home. In December 2016, Rainsy was sentenced in absentia to five years in prison.

In September 2017, CNRP deputy leader Kem Sokha was arrested for treason and Mu Sochua (one of the authors), the CNRP’s third-ranking member and one of Cambodia’s most prominent female opposition figures, fled abroad after being warned of her imminent arrest. By the end of 2017, approximately half of the CNRP’s parliamentary members had fled overseas.

The situation for media and journalists critical of the government also deteriorated rapidly. In July 2016, Kem Ley, a prominent political analyst and journalist known for his sharp criticism of the government, was assassinated. In July 2017, the government arrested dozens of critics and shut down 18 radio stations, including the Cambodian operations of Radio Free Asia and Voice of America.

In November 2017, Cambodia’s Supreme Court dissolved the CNRP, citing an alleged foreign-backed plot to overthrow the government. This led to the loss of all 55 parliamentary seats held by the CNRP, as well as 5,007 commune council seats. In addition, 118 key party members were barred from politics for five years to prevent members of the dissolved CNRP from regrouping. As a result, various movements advocating for labor rights, land rights, women’s rights, environmental protection, and other causes lost their leaders and core participants. Cambodia’s civil and social rights, for which the people had fought for decades, were sacrificed.

Cambodia’s journey from democracy back to authoritarianism, and China’s influence in the process, goes beyond merely supporting Hun Sen financially. It also involves replicating China’s development model in Cambodia. With China’s backing, Hun Sen not only cracked down on the opposition in just two years, but has also fully embraced the “China model” in the last eight years. Cambodia has become a haven for Chinese-operated cyber scams, where people, often young and well-educated, are tricked into working in slavery-like conditions and forced to defraud people online.

Development projects are carried out without regard to social and environmental impacts. In September 2023, the BBC reported that development of the Dara Sakor seashore resort remains unfinished after 15 years, but has been carried out with little or no evaluation of the human and environmental costs. In mid-2020, the United States imposed sanctions on Union Development Group (UDG), the Chinese company that owns the project.

Cambodia’s role in the geopolitical competition between the United States and China is becoming increasingly important. On July 26, Voice of America reported that Cambodia was nearing completion of the Chinese-backed Ream Naval Base in the southwest Cambodian province of Sihanoukville. This conclusion was based on satellite imagery from the American satellite imaging company BlackSky. The base’s dock is similar in size and design to the one at the Chinese People’s Liberation Army base in Djibouti, measuring 335 meters in length and capable of accommodating various types of warships, including aircraft carriers.

If Chinese warships are stationed there, the Ream base will hold the greatest strategic value in the South China Sea conflict and it will also enhance China’s naval capabilities in the strategic Strait of Malacca. While China’s navy is bigger than the U.S. Navy, it lacks the extensive international base network and logistical facilities needed for a blue-water navy capable of sailing worldwide. Access to the base in the Gulf of Thailand will give China a strategic advantage.

Cambodians have shown their thirst for democracy by turning out in large numbers to vote in every election since 1993 in which there has been a semblance of choice. A renewal of political will on the part of the international community can help return the country to the path of democracy set forth in the Paris Peace Agreements of 1991. Continued support for the Hun family dictatorship is not only a betrayal of the democratic rights of the Cambodian people, but also allows China free rein to advance its military and strategic interests. The West can help limit the expansion of Chinese power by taking a stand on Cambodia and insisting that recognition and normal trade privileges will only be granted to a democratically elected government.