With less than two weeks remaining until Argentina’s presidential election, Javier Milei, the unconventional “anarcho-capitalist” candidate, maintains his lead in the polls against four other contenders. His surprising victory in the August primaries can be largely credited to his commitment to dollarize the Argentine economy, a move perceived as the final solution to the nation’s economic turmoil.

Argentina’s dollarization would signify a profound transformation, involving the abandonment of the peso and the dissolution of the Argentinian central bank. This potential move, along with Milei’s anti-China rhetoric, raises a significant yet often overlooked issue concerning the continuation of the currency swap line established between the Central Bank of Argentina (BCRA) and the People’s Bank of China (PBOC), which has been recently used to avoid a default on Argentina’s repayments to the International Monetary Fund (IMF).

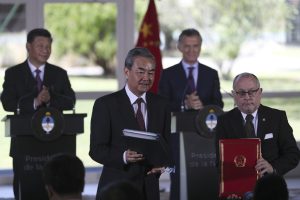

In 2014, an iterated version of the Sino-Argentina bilateral swap line (BSL) was formed as part of a comprehensive strategic partnership between the two countries. Over time, it has become a crucial source of financial support for Argentina when it faces cash shortages.

The recently released IMF Staff Country Report highlighted the fact that the BSL accounts for a significant portion of the BCRA’s international reserves and plays a vital role in offering short-term liquidity support to help Argentina service its external debt obligations and finance imports. The PBOC recently agreed to the BCRA’s request for another three-year term and doubled the accessible portion of the swap to nearly $10 billion, signifying a strengthened bilateral partnership.

However, if Milei were to emerge as the winner in the October 22 election, there would be considerable uncertainty surrounding the continuation of the swap line with China and Argentina’s ability to repay the IMF in the event of dollarization. This radical shift potentially signals a reorientation of Argentina’s economic strategies, which could reverberate through its trade dynamics and diplomatic relations with China.

The Evolution of the Argentina-China BSL: An Asymmetric “Tango”

Bilateral currency swap lines, established by two monetary authorities, offer mutual insurance during periods of financial instability by enabling the exchange of currencies at predetermined interest rates and exchange rates. Beginning in 2008, China embarked on building its own global network of central bank swap lines, rapidly gaining momentum due to its strong commitment to internationalization of the renminbi (RMB) and the growing interest of emerging markets in seeking alternative sources of financing. As of May 2023, China has entered into bilateral currency swap agreements with over 40 countries and regions, with a total value exceeding 4 trillion RMB ($582.3 billion).

Among China’s various swap agreements with different countries, its arrangement with Argentina stands out due to its longevity and extensive utilization. The BCRA was among the early adopters of swap agreements with China, and it remains one of the few institutions that have extensively accessed the PBOC swap line to address liquidity stresses.

A brief history provides context. The first Argentina-China BSL, valued at 70 billion RMB (approximately $11 billion), was signed in 2009 for a three-year term. Although it was the largest financial agreement between China and any Latin American country at the time, the original arrangement was never activated until it was amended in 2014 by a renewed deal with significant improvements in flexibility, functionality, and affordability. The 2015 supplementary agreement further expanded its capabilities by allowing the BCRA to convert up to 20 billion RMB from the swap line into U.S. dollars. This transformation elevated it from primarily serving as a local currency trade settlement mechanism into the lender of last resort to finance fiscal debt.

Although both parties have an equal option to activate the swap line as needed, the dynamic in the Sino-Argentina BSL is characterized by asymmetric dependence. While the United States typically acts as the lender in such agreements, China’s substantial foreign reserves and strong economic fundamentals also empower it to take on the lender’s role, giving it the authority to approve or reject the BCRA’s request for a swap draw. When the need for liquidity arises, the BCRA can initiate a request, and upon approval from the PBOC, RMB is deposited into the BCRA’s account at the PBOC. In return, the PBOC receives an equivalent amount of peso as collateral. At the end of the repayment period, usually around one year, the BCRA pays back the RMB at a predetermined interest rate, reported to be between 600 and 700 basis points.

Since its activation in 2014 to counter severe currency depreciation, Argentina has consistently turned to the PBOC swap line, and its dependence has steadily increased. According to research by Vincient Arnold, the BCRA has maintained outstanding balances under the swap arrangement ranging from $2.6 billion to $20.5 billion between 2014 and 2021. During this time frame, the ratio of swap obligations to foreign reserve obligations increased from 8.2 percent to 51.6 percent.

Over time, this trend has intensified as Argentina’s economy has descended further into turmoil. During the tenure of then-President Mauricio Macri’s right-wing administration in 2018, there was an attempt to reduce reliance on the PBOC swap line by seeking funding from the IMF. However, the record $57 billion bailout from the IMF failed to resolve Argentina’s economic troubles.

By 2022, Argentina’s deteriorating economic situation had pushed it to the brink of default with the IMF. Even though a last-minute deal on debt restructuring was reached in 2022, Argentina continued to struggle to meet its regular payment obligations. Starting this year, Argentina, for the very first time, turned to the PBOC swap line to repay the IMF. According to the IMF’s Staff Country Report as of mid-August, Argentina had drawn $2.7 billion from the PBOC swap line (including a bridge loan) twice in the span of 30 days to avert default with the IMF. Beyond debt financing, an additional $2.7 billion in swap draws was allocated for financing imports ($1.8 billion) after the peso suffered a selloff and servicing debt obligations to bondholders ($900 million).

The Future of the Argentina-China BSL: Tango Tangles?

The recent repayments by Buenos Aires to finance its IMF debt highlight Argentina’s growing dependence on the PBOC swap line. Nevertheless, the potential replacement of the China-friendly incumbent, Alberto Fernández, by the Trump-like Javier Milei introduces uncertainties regarding whether Argentina will continue making payments to the IMF in the future and whether it will have the need – and the ability – to utilize the swap line once more.

The swap line with China is believed to currently hold the key to avoiding Argentina’s IMF default, according to Matthew Mingey, a senior analyst with Rhodium Group. However, Milei’s proposal to abolish the central bank presents a distinct challenge to it. This is because the swap line was established through bilateral agreements involving central banks and the currencies of both countries, as mentioned earlier. In this arrangement, the BCRA is the sole eligible party on Argentina’s side to manage its bilateral swap line with its Chinese counterpart. If the BCRA and the peso were to be abolished, the swap line would become essentially meaningless.

Hence, several crucial questions come to the forefront: Who would step into the BCRA’s shoes when it comes to managing the unwinding of the swap line with China? Dollarization won’t occur overnight. Would China continue to provide access to swap lines for Argentina, considering that the PBOC swap line might remain in place for a transitional period?

Milei’s chief dollarization strategist has put forward a suggestion to establish a dedicated fund in an OECD jurisdiction as a means to take over the responsibilities of the BCRA in managing the country’s reserves and dealing with short-term peso debt. However, there hasn’t been a clear plan laid out yet for managing the bilateral financial agreements that the current administration has entered into, including the swap agreement with China. While the primary focus of this specialized fund is to repay the $26 billion worth of debt instruments held by commercial banks, there hasn’t been any discussion about how to address the debt resulting from the currency swap arrangement with China.

Regarding the second issue, empirical evidence indicates that these agreements often have an asymmetrical nature, giving China a significant upper hand when it comes to deciding when and how to activate, extend, or expand swap lines. This advantage has led some scholars to argue that China strategically utilizes this leverage to either reward or penalize partner countries based on their alignment with China’s political positions. However, it’s important to note that being a creditor also exposes China to exchange-rate risks related to the borrowed currency. In the case of the swap line with Argentina, China provides liquidity and, consequently, assumes the credit risk associated with Argentina’s borrowing. If Argentina encounters difficulties in repaying the swap, China could potentially incur losses due to exchange rate risk.

In a less optimistic scenario, some Chinese scholars surveyed are suggesting that China may need to take a tougher stance if Milei adopts a more assertive posture toward China by aligning closely with the United States. A Chinese scholar associated with a state-run think tank stated, “China should insist that the new government either tones down its anti-China rhetoric, or else, we should withdraw our funding.”

While an immediate termination of the swap deal may not be imminent, China could opt not to offer further access to the swap line. In such a situation, the primary concern on the Chinese side revolves around the management of the activated portion of the swap line, which stood at $6.5 billion as of mid-August. Any mishandling of this situation would undoubtedly trigger domestic backlash, particularly amid economic downturns.

Considering China’s past dealings with pro-U.S. administrations like those of Mauricio Macri and Brazil’s Jair Bolsonaro, it’s likely that Beijing would adopt a more pragmatic and cautious approach to settle the swap line with Argentina. In 2018, when Argentina faced economic challenges similar to those it faces today, Macri chose not to activate the PBOC swap line but instead turned to the U.S.-backed IMF, securing a record-breaking $50 billion bailout program.

Surprisingly, China did not respond by freezing the swap line. Instead, China used it as leverage to distance Argentina from its alignment with the United States. During Chinese President Xi Jinping’s visit to Buenos Aires in December 2018, an additional 60 billion RMB was added to the original swap line as part of a package of 30 trade and investment bilateral deals. These moves effectively softened Macri’s pro-Washington agenda. Similarly, Bolsonaro’s initially tough stance against China saw a significant shift as Beijing increased its investment commitments to help boost Brazil’s sluggish economy.

It is evident that when politicians in favor of closer ties with Washington prioritize business interests and avoid causing political discomfort, Beijing has shown openness to maintain cooperation. This principle could also be applicable to Javier Milei, if he is indeed victorious in the presidential election. One key challenge associated with his dollarization plan is the implementation phase. The central bank must exchange all of its liabilities in

domestic currency for U.S. dollars. If Milei cannot secure sufficient financial resources from multilateral institutions, he may reevaluate the potential for accessing a swap line with China or explore alternative avenues for securing financing from China.

Milei’s proposal for dollarization is estimated to cost the already cash-strapped economy $40 billion. He and his team are now exploring various options to raise these funds but have yet to provide a convincing plan. Possible solutions include sourcing funds from repatriating assets held abroad or reintegrating unreported cash into the financial system. Additionally, the special-purpose fund mentioned earlier would serve as collateral for potential borrowing. This fund would consist of treasury bonds, debt from the public pension fund, and shares in the state oil company.

However, skeptics argue that Argentina has been excluded from the international bond market since its default in 2020, with few investors willing to engage in any transactions involving Argentine bonds. As a result, Argentina has few current external financing options other than China and Qatar, the other bilateral lender helping Argentina repay the IMF.

Milei’s inability to secure such a substantial amount of funding through market channels would limit his ambition to dollarize the country’s economy and prompt him to consider a path similar to his predecessors by seeking funding from China. If Milei moderates his China policy, China could potentially continue financing a dollarized Argentina, regardless of whether a swap line is in place. In this context, there are parallels with China’s efforts to cultivate strong ties, both in finance and trade terms, with dollarized economies like Ecuador and El Salvador.

The lack of a swap line does not necessarily discourage China from lending money to Ecuador. In total, Ecuador took on about $18 billion in loans from China, mainly during the presidency of Rafael Correa, an anti-U.S. leftist. These funds were obtained through Chinese state-owned banks for various infrastructure projects or through prepayment agreements, in which Chinese oil companies provided upfront cash in exchange for future oil sales. When pro-American conservative Guillermo Lasso assumed office, despite his prior criticisms of Chinese loans, China extended oil-backed loans and agreed to restructure $4.4 billion of Ecuador’s debt, resulting in the country saving $1 billion from 2022 to 2025. 2025.

In the case of El Salvador, its vice president, Félix Ulloa, said that China had offered to acquire the country’s $21 billion in foreign debt. Nevertheless, the spokesperson for the Chinese Foreign Ministry declined to provide any official response to this claim.

China appears undeterred in strengthening trade ties with dollarized economies either. Earlier this year, Ecuador’s President Lasso successfully negotiated a free trade agreement with China, expected to expand export opportunities by nearly $1 billion. According to the United Nations COMTRADE database, Ecuador’s trade data with China indicates that its exports steadily increased from around $500 million in 2013 to $4.07 billion in 2021, despite the lack of local currency settlement facilitation.

In contrast, Argentina’s exports to China have fluctuated between 2014 and 2022, and it maintains a trade deficit with China, despite its swap line doubling since its initiation. Moreover, research has suggested that the trade effects on currency swap agreement partner countries not participating in the Belt and Road Initiative are less pronounced.

When we compare Ecuador and Argentina, it becomes clear that the trade relations between China and Argentina hold greater significance in terms of both quantity and geopolitical impact. For Argentina, its exports to China, which is its second-largest buyer, constitute a crucial source of consistent revenue. This income is vital for replenishing the country’s depleted reserves and achieving the financial goals established with the IMF.

Furthermore, maintaining stable trade relations with Argentina aligns with China’s strategic objectives, particularly in securing essential resources like lithium and soybeans from countries that are not closely aligned with the United States. Disrupting these trade ties would not be in the best interest of either party. In this context, it appears that discontinuing the swap line between China and Argentina would have limited repercussions on their overall bilateral trade relations.

Conclusion

“It takes two to tango,” as the saying goes. As a potential dollarization unfolds, the destiny of the bilateral swap line is entangled with the broader economic and policy dynamics between China and Argentina. Milei’s challenges in addressing Argentina’s multifaceted problems, coupled with China’s interests in maintaining a stable bilateral relationship, suggest that pragmatic considerations may ultimately chart the course ahead.

If elected, Milei will quickly find himself grappling with mounting challenges both within and beyond Argentina’s borders. The nation teeters on the precipice of an ever-deeper recession, as inflation skyrockets far above 100 percent and international reserves dwindle. The IMF faces mounting pressure to adopt a tougher stance on Argentina, ensuring its commitment to economic targets and debt obligations. It’s a daunting task to envision how Milei will navigate these economic and financial hurdles while simultaneously attracting sufficient funding for his dollarization strategy.

This challenging scenario may ultimately prompt Milei to reevaluate Argentina’s access to the swap line with China as he pursues the path of dollarization. Meanwhile, a disruptive bilateral relationship with Argentina isn’t in China’s best interest. China should be able to find a pragmatic resolution with Argentina to address the issues surrounding the bilateral swap line. This doesn’t necessarily rule out the possibility of Argentina continuing to access the swap line for a certain period. In this intricate economic diplomacy, practicality is likely to guide the steps of both nations as they navigate these complex challenges.