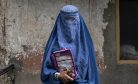

In March 2022, attending school beyond sixth grade became a crime for girls in Afghanistan. By December last year, young women found themselves barred from entering their university campuses by armed guards. Since the fall of Kabul in August 2021, Afghanistan’s Taliban rulers have implemented a system of governance in which women find themselves increasingly restricted and institutionally subordinated, though many had hoped that schooling would remain open for all.

Despite the Taliban’s early pretense of respecting human rights, the millions of women and girls previously enrolled in schools and universities find themselves banned from attending educational institutions, making Afghanistan the only country in the world where girls cannot study beyond primary school. It is hard to overstate, or even imagine, the despair of an entire generation of girls and women mourning their right to education and the futures they deserve. Sixteen-year-old Atefa, in a 2022 interview with Human Rights Watch researcher Sahar Fetrat, offered a glimpse into her grief: “For Afghan girls, the earth is unbearable, and the sky is unreachable.”

For the people of Afghanistan, these circumstances are a somber echo of the past, as education for girls was also outlawed during the Taliban’s first reign between 1996 and 2001. Mirroring the strategies of their previous rule, the Taliban’s attack on education encompasses a radical overhaul of the school curricula to support their extremist ideologies, in what seems to be a mission to transform the education system into a chain of madrassas focused on indoctrination. Entire subjects, including visual arts and civil education, are being erased from the schooling system, and all images of living beings are being removed from textbooks. The prohibitions extend to the celebration of Nowruz, advocacy for democracy and human rights, encouragement of music, and mentions of non-Muslim figures and elections. The decades-long progress made by education activists and women’s rights campaigners to restore the country’s academic system has been dismantled in just a few years.

But like previous generations of Afghan women, this generation is finding ways to resist the oppressive forces thrust upon them. Fawzia Koofi, Afghanistan’s first female deputy speaker of parliament, shared in a meeting at the United Nations’ gender equality conference (CSW67) the novel tactics that women are using to access knowledge and educational resources, harnessing digital platforms to connect to other university students, professors, and international educational opportunities such as online degrees from U.S. universities. An online education cannot replace a regular education, Koofi noted, but in the absence of formal schooling, women and girls are leveraging the available technologies to their benefit.

In addition to online options, underground girls’ schools have also emerged throughout the whole country in defiance of the education ban. These clandestine education centers take various forms: private schools that have decided to keep their doors open to girls; informal classes held in local mosques or the homes of teachers; and even underground book clubs where girls gather to read and promote discussion.

These efforts seem to be just as much about boosting morale and engendering a sense of symbolic power as they are a temporary replacement for a formal education system. Mahdia*, a recent graduate from one of Afghanistan’s top universities, set up a school teaching seventh grade classes in a mosque near a provincial capital. She explained to journalist Emma Graham-Harrison of The Guardian: “I do this as a volunteer, to support the girls and create hope in their future… Every day when we start and finish I talk to them a bit, and try to motivate them, with messages like ‘no knowledge is wasted.’”

Much of the online teaching is being arranged by those living outside of the country. Angela Ghayour, education activist and refugee in the U.K., founded Herat School, which has enabled hundreds of experienced teachers to offer more than 170 different online classes, including math, music, cooking, and painting, delivered via Skype or Telegram.

Underground schools also supported girls during the previous era of Taliban rule, some covertly funded by aid agencies, though less was known about them during that time.

Of course, protesting the Taliban’s draconian policies involves many sacrifices, as illegal classes pose a great risk both to the adults organizing them and the students attending them. Teachers employ various tactics to avoid exposure – keeping lessons short, reminding girls to dress according to the Taliban’s mandate so their attire is no excuse to be stopped, and preparing excuses in case inspectors discover them. The best excuse is that they are simply gathering to study the Quran.

But operating under constant fear of detection and threat of punishment takes a heavy toll. “I have noticed plenty of changes in our students… they used to come with lots of energy and excitement. Now they are never sure if this will be their last day in class. You can see how they are broken,” said the head teacher of a school in Kabul.

Women are now campaigning for the situation in Afghanistan to be termed a “gender apartheid” and recognized as such under international law. Applying that formal label will serve as a means to trigger global legal accountability and “expand the set of moral, political and legal tools available to mobilize international action” against regimes of systematic gender-based oppression.

After all, women and girls’ right to education is about more than just access to classrooms. It is also about ensuring that girls feel safe in those classrooms and enter them on equal terms with their male counterparts; that they are empowered to pursue their desired academic and professional aspirations, and are afforded the liberty to make decisions about their own lives. While international leaders neglect to take meaningful, coordinated action, women and girls in Afghanistan and in exile remain on the frontlines of resistance.

As education activist Pashtana Durani shared in an interview, “We all have to choose our own battles. This is mine. I’ll raise an army, just like they did – except that mine will be of educated, determined women.”

* Some names are changed or shortened for their protection.