The issue of global debt distress is a matter of great concern, not just for the affected developing nations but also for developed countries and international organizations. A recent United Nations Development Program report revealed that 54 developing economies are currently grappling with severe debt problems. Among these nations, Ghana, Zambia, and Sri Lanka have found themselves in dire financial straits. Sri Lanka’s government declared bankruptcy in April 2022, temporarily suspending external debt repayments until a consensual restructuring plan aligned with the International Monetary Fund’s economic adjustment program could be established. Ghana defaulted in December 2022, while Zambia faced financial difficulty in repaying loans back in June 2020.

Common Challenges in Ghana, Zambia, and Sri Lanka

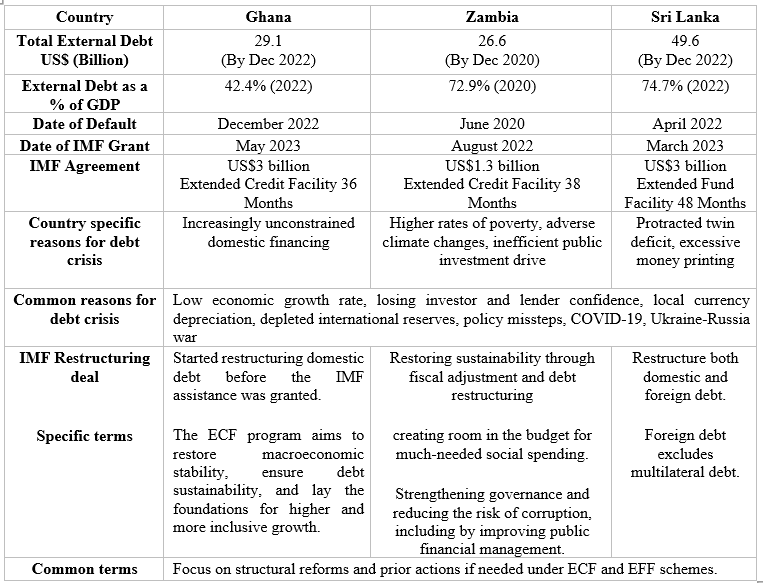

The debt crises in Ghana, Sri Lanka, and Zambia share a common theme of policy mismanagement that has given rise to structural imbalances in their respective economies. While each of these countries faced unique challenges – Sri Lanka with excessive money printing and disruptive agricultural policies, Ghana with impractical election promises, and Zambia with allowances for specific employment and climate vulnerabilities – the underlying problems were not unique to these cases. These nations have grappled with inadequately structured tax systems, the middle-income trap, and the challenges of restructuring bilateral debt with China. The following table summarizes the reasons for debt crises in the three countries.

- Source: International Monetary Fund (2023), Central Bank Annual Report (2022), External Resource Department of Sri Lanka (2023)

In Sri Lanka, policy lapses and economic mismanagement led to a multifaceted disaster. Ill-timed tax reductions, rushed attempts to adopt organic agriculture, depletion of official reserves while striving to maintain a flawless debt servicing record, delayed exchange rate adjustments, and a failure to listen to early warning signals contributed to an economic catastrophe. As foreign exchange reserves dwindled and economic growth rates declined, investor confidence plummeted.

Misappropriation of funds and impractical election promises in the form of tax cuts and subsidies in Ghana also speeded its economic downfall. The major tax reforms included the abolishment of VAT/NHIL on real estate, financial services, and import duties as well as tax reductions on the national electrification scheme levy, public lighting levy, and special petroleum tax rate.

In Zambia, while the situation was slightly different, fiscal imbalances also created additional debt pressures. Zambia reinstated allowances for selected employment-related benefits and faced economic shocks due to climate vulnerabilities, which placed increasing pressure on the domestic economy.

The three countries faced the same consequences: servicing external debt obligations in foreign currencies became increasingly difficult, forcing these nations to rely on private credit markets to obtain foreign exchange for debt servicing and essential imports. That ultimately compounded their debt problems, leading to sovereign defaults.

IMF Financial Assistance

All three countries consulted the International Monetary Fund (IMF) as a last resort to handle their debt crises, and the IMF showed willingness to offer support under certain conditions. Due to their lower-middle-income status, Ghana and Sri Lanka were treated differently from Zambia, a low-income country. Ghana and Sri Lanka had to agree to restructure their domestic debt before receiving financial assistance, while Zambia had the opportunity to ignore domestic debt restructuring.

Ghana received a $3 billion Extended Credit Facility (ECF), Sri Lanka a $3 billion Extended Fund Facility (EFF), and Zambia a $1.3 billion ECF. Zambia stood out as the only nation among the three to benefit from the Highly Indebted Poor Countries (HIPC) initiative, which enabled the restructuring of debts with senior creditors such as the World Bank and Asian Development Bank. This safeguarded Zambia’s development goals from being compromised by unsustainable debt and gave access to more robust forms of debt relief.

This stark difference marks the “middle-income trap” as part of the ongoing global debt crisis. The debt-distressed countries requiring additional concessional financing are predominantly of middle-income status, highlighting the need for better mechanisms to address debt distress beyond the traditional measures.

The Role of China in Debt Restructuring Negotiations

China plays a pivotal role in the global conversation on the debt crisis, as shown in the three developing nations considered here. China accounted for around 17.6 percent of Zambia’s external debt. In Ghana, only 3 percent of external debt is owed to China; however, this debt is collateralized against natural resources such as cocoa, bauxite, and oil. China is Sri Lanka’s largest bilateral creditor, to whom Sri Lanka owes around 45 percent of its bilateral debt. Because China is such a major bilateral creditor and faces its own domestic debt pressures, this created additional challenges when restructuring debt as part of Sri Lanka’s IMF agreement.

Debt servicing payments comprise a significant source of China’s government revenue due to its status as a major global bilateral creditor through the Belt and Road Initiative. Hence, China is cautious not to set a precedent for generous and straightforward debt restructuring, as this may open the door to serial defaults on bilateral debts, further exacerbating economic pressures. Considering these issues, as a strategic creditor with less appetite for losses, China typically prefers lengthy extensions on debt repayments and resists any reductions in the outstanding principal.

This was the experience of Zambia. In its eventual deal with the Export-Import Bank (Exim) of China, both sides agreed to reduce the coupon on its $4 billion in recognized official claims to 1 percent for the remainder of Zambia’s IMF program. The agreement with China will see Zambia pay interest rates as low as 1 percent until 2037 and push out maturities on $6.3 billion in bilateral debt to 2043, representing an average extension of more than 12 years.

As for Sri Lanka, after President Ranil Wickremesinghe’s visit to China in mid-October, Sri Lanka confirmed that it has reached a deal with China, regarding $4.2 billion of debt. This is a positive sign for receipt of the second IMF tranche. State Minister for Finance Shehan Semasinghe said the agreement reached with the IMF and the staff-level agreement reached following the first review of Sri Lanka’s EFF arrangement will help settle arrears owed to multilateral creditors while expediting the debt restructuring process.

This may give reassurances to Ghana, which is yet to finalize a debt restructuring deal with China, as it aims for a flexible and cordial response from creditors with the support of the IMF. However, the difficulties faced by Ghana, Zambia, and Sri Lanka when restructuring their bilateral debt with China may ward off other potential defaults in the developing world.

Lessons Learned

Developing countries that default before initiating the debt restructuring process show relatively higher losses for investors. The experiences of Ghana, Zambia, and Sri Lanka suggest that reaching out to the IMF before a default is crucial to preventing rejection by potential lenders.

This situation should serve as a wake-up call for the World Bank, IMF, and other multilateral organizations to evolve mechanisms that address this unprecedented debt crisis and promote better initiatives for economic development. Without effective debt restructuring, relief, or forgiveness, middle-income debtor nations risk falling into a debt trap where economic policies focus solely on servicing unproductive debt repayments to creditors and propping up an unfair global financial system.

Many developing economies classified as middle-income countries are deprived of concessional financing opportunities and more generous debt relief mechanisms, such as the HIPC, provided by international organizations. This must signal to multilateral organizations that mechanisms must evolve to support debt-distressed middle-income countries, who currently dominate global debt distress. Multilateral organizations must support these economies individually to reduce their debt levels, rather than holding them back as a result of arbitrary income categorization and a “one-size-fits-all” approach.

Prolonged debt restructuring processes due to delays from major creditors have increased debt burdens over time. Timely discussions are essential for safeguarding a debt-ridden nation’s financial stability and mitigating potential economic repercussions from prolonged debt restructuring. The challenges associated with IMF policies necessitate access to alternative sources of concessional finance to address the opportunity costs of debt. It is imperative to navigate these turbulent waters and ensure that nations are not held hostage by debt but rather empowered to build a brighter economic future.

This article is based on an explainer titled: “Borrowing Wisely: Gaining Insights from Debt Restructuring in Ghana, Sri Lanka and Zambia” published by Lakshman Kadirgamar Institute of International Relations and Strategic Studies.