On November 17, 2022, the Australian economist Sean Turnell was released from prison in Myanmar after nearly two years of isolation. As an adviser to the country’s civilian leader Aung San Suu Kyi who had spent many years living and working in the country, Turnell was arrested shortly after the military coup that unfolded on the morning of February 1, 2021. He spent the next 650 days being held in horrific and unsanitary conditions in a number of locales, including Insein Prison in Yangon, built by the British in the late nineteenth century, which has housed several generations of political prisoners.

After his release, as he was being escorted out of the country, Turnell was asked by a military government official, “Do you hate Myanmar now?”

“I never hate Myanmar,” Turnell replied. “I love the people of Myanmar and it’s always like that.”

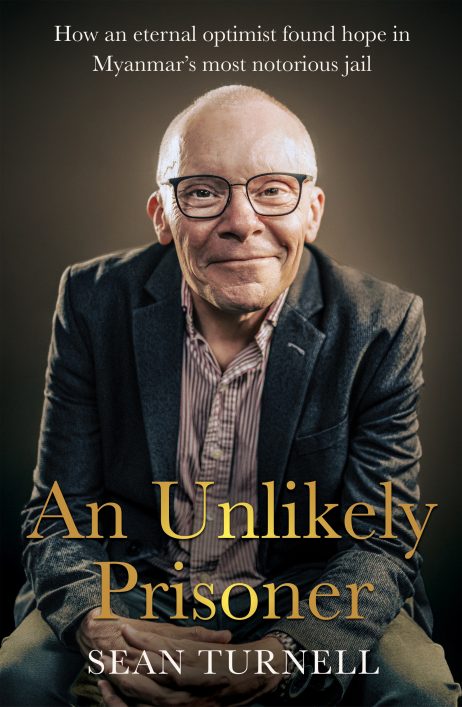

In tune with this sentiment, Turnell has since become a vocal advocate for the people of Myanmar and their current attempt to overthrow the military and extricate it permanently from the country’s political life. This, and the details of his arduous prison ordeal are detailed in a new book, “An Unlikely Prisoner.” Turnell spoke with The Diplomat about how he endured prison, the roots of the 2021 coup, and the “Manichean struggle” that is now unfolding for the future of the nation.

Let’s start with the morning of February 1, 2021, which was supposed to be the opening session of Parliament in Naypyidaw. How did the day unfold, and what was your first hint that something was amiss?

I heard in the very early AM from a source in Washington that the coup was underway. I was at that point still in my quarantine hotel (the same place I was arrested 5 days later) but had come out of COVID-19 quarantine just the day before. Rumors were thick the day before, but I remained hopeful a coup would be avoided. I knew the talks on Saturday (January 30) had broken down, but I still harbored the view that the idea of a coup was so irrational, and so damaging even to the plotters themselves, that they would not go ahead with it.

Upon hearing the news my first reaction was to check on the status of my Myanmar friends: who had been arrested, who was still free, who I could help to get to safety. This latter aspect became my principal activity for the next few days. At first I was not of the view that I would be arrested, but probably just deported at some point. In any case, my own situation was out of my control – there were no seats on any flights out for me.

Why do you think that of all the foreigners detained during and in the aftermath of the coup, you were singled out for such a relatively lengthy period in detention? According to media reports from the time, you were attempting to flee the country with “secret state financial information.” Was it ever clear what the accusations against you were, or were you simply singled out for attention due to your association with Aung San Suu Kyi?

I would not hear of the specific allegations against me for another six months or so, even though I had a vague idea it would all revolve around the Official Secrets Act. The whole “flee the country” bit was absurd of course. I could not go anywhere, and I’m sure they knew where I was throughout.

Why me? One simple reason: I was there. Most other foreigners assisting the government were still stuck outside the country because of COVID-19; some had got out with the assistance of their governments; some were not so high profile, therefore not then on the SAC’s radar. My arrest was useful to the SAC [State Administration Council] – in painting a narrative that somehow the NLD [National League for Democracy] government was a puppet of sinister foreign hands that were pulling all the strings. As I detail in the book, I would be accused later of simultaneously working for MI6 and George Soros (thus uniting quite a number of paranoid conspiracy tropes), and being the puppet master of Daw Suu, the ministers etc. The one card they thought they had was that they were nationalists, keeping Myanmar safe from foreigners. Of course, they have all but impoverished and destroyed the country, and they leave it (today) as easy prey to any number of true threats to Myanmar’s sovereignty.

Why me? One simple reason: I was there. Most other foreigners assisting the government were still stuck outside the country because of COVID-19; some had got out with the assistance of their governments; some were not so high profile, therefore not then on the SAC’s radar. My arrest was useful to the SAC [State Administration Council] – in painting a narrative that somehow the NLD [National League for Democracy] government was a puppet of sinister foreign hands that were pulling all the strings. As I detail in the book, I would be accused later of simultaneously working for MI6 and George Soros (thus uniting quite a number of paranoid conspiracy tropes), and being the puppet master of Daw Suu, the ministers etc. The one card they thought they had was that they were nationalists, keeping Myanmar safe from foreigners. Of course, they have all but impoverished and destroyed the country, and they leave it (today) as easy prey to any number of true threats to Myanmar’s sovereignty.

Tell us a bit about the conditions in which you were held. How were you treated, and how much contact did you have with the outside world and with other political prisoners? Did you get any sense of the protests that swelled in Myanmar’s cities in the immediate aftermath of the coup, and the armed uprising that followed?

The conditions under which I was held were dreadful – throughout the entire 650 days. My accommodation ranged from a windowless “Box” (the first two months), an ancient and decrepit concrete prison cell in Insein (next six months), more or less the same in Naypyidaw Jail (for the next 12 months), and then back in Insein on “death row” (the final two months). In the book I describe the filth of the cells, their exposure to the elements, that they harbored all manner of insects and rodents, and were the breeding grounds for disease. Food was of very poor quality and delivered in ways that were “hygienically challenged” in ways that, again, just made the process an incubator of all manner of illnesses. I did have access to other political prisoners, more or less throughout except for the first and last two month periods (both times in which I was in solitary confinement). My political prisoner friends were fantastic, and they saved my life.

Through Embassy phone calls (in which I was able to talk to my wife, Ha Vu), I was able to understand something of what was going on in the world outside. Whilst in Insein I was able to hear the gunfire, explosions, etc as the military turned on the demonstrators. Of course, I was also in Insein when the prison itself was bombed (I heard the explosions that took place in the parcels center, for instance, during my final stint there). Of course, rumors continually spread in a prison – some accurate, some not – so I had a pretty good idea of what was happening outside.

When I was in The Box in CID headquarters (just outside the walls of Insein) on a couple of occasions I heard my name being shouted by protestors.

Of course, I also heard the sounds of prisoners being tortured whilst I was in The Box.

I was not tortured in the way many of my Myanmar colleagues were, but I was punched, kicked, had my hair singed, and treated especially brutally during prison transfers. All of this is detailed in the book too, and how Myanmar colleagues helped protect me from the worst of it.

Prior to the coup, you had a close working and personal relationship with Aung San Suu Kyi, a much mythologized figure who still retains a talismanic status for opponents of the military. Did you have any inkling of the fraying relationship between Aung San Suu Kyi and the military top brass prior to February 1? What do you believe prompted the military takeover?

I had some knowledge of this fraying relationship, but not a lot. My remit was very much on the economy – so I really knew no more than any other close observer of Myanmar on these things.

From all of my discussions in the prisons with people who really knew the full, inside story, it would seem Min Aung Hlaing’s personal interests were paramount factors in the coup (and of a compliant cohort around him). However, I think the economic reforms were something of a factor – slowly but surely the encrusted military and crony businesses were feeling the heat of liberal (market opening) reforms. Some very powerful people were fearful that the old rent-seeking order was under threat.

One aspect of the post-coup situation that has received less international attention is the near-collapse of Myanmar’s economy. Speaking as an economist, what impact has the advent of this new military junta had on the country’s economy, and how do things differ from the situation under previous military juntas? Do you see any signs of improvement under the current leadership?

Myanmar’s economy today seems as bad as it has ever been. The amount of destruction – physical, yes, but institutional (trust, norms, policy processes, confidence, etc) is extreme. The difference to the past is that this junta does not seem to even pretend anymore that it has any sort of vision for Myanmar – except that the country exists as a place to extract wealth and resources to maintain their power. It’s all just a Manichean struggle now between a bunch of pitiless yet clueless gangsters, and a people trying to free themselves from them. The SAC regime seems to resemble more a criminal cartel than anything resembling a “government.”

In years past, you were never reticent about issues pertaining to Myanmar, but since your release you have been especially vocal in condemning the cruelty and inhumanity of the current military administration. With resistance offensives currently unfolding in various parts of the country, and the economy in a moribund state, what do you think the outside world should do now to prevent military atrocities and increase the chance of a positive outcome for Myanmar and its people? Is there anything that the outside world can do?

Given that this is now a struggle over resources as noted, it seems to me that what the international community must do is to restrict the means by which Myanmar’s military junta wages war against its own people. Sanctions and the like should no longer be about signalling disapproval or anything like that, but are needed to limit the junta’s capacity to kill, maim, rape, and imprison.

Did your ordeal change your relationship to and perception of Myanmar and its people? If so, how?

Funnily enough, it did not. The people of Myanmar are the first and major victims of this small gang that rules them, and the latter are not remotely representative of the country. Myanmar people showed themselves to me, even (especially!) in extremis, to be the most courageous and compassionate people I have ever come across. I give many examples in my book, but to grab just one I will nominate the story of the young girl I encountered in a crowded and hellish prison van, and her offering to me of a cake. That, to me, is Myanmar.